Emily Katral

Emily Katral earned her Bachelor of Arts in Psychology from Capilano University in the spring of 2025. During her undergraduate studies, she developed a deep interest in developmental psychology, Indigenous epistemologies, and literary analysis— exploring how diverse ways of knowing intersect with mental health and education.

In her final semester, Emily completed a practicum as a student support aide in a high-needs public elementary school, an experience that profoundly shaped her academic direction. Through witnessing firsthand the impact of under-resourced mental health support in schools, she recognized the urgent need for preventative care and systemic reform within public education. Emily plans to pursue graduate studies in school and clinical child psychology, with a focus on strengthening mental health access and outcomes for vulnerable youth.

My time as a student support aide in a high-needs public elementary school brought me face to face with a painful truth: access to functional mental health support for young children is not being treated as the urgent provincial priority that it needs to be. There is a massive discrepancy between policy intentions and the lived experiences of students and faculty on the ground. Funding efforts that try to increase learning outcomes fall short when students have difficulties learning due to unaddressed mental health challenges. For children facing mental health challenges, no matter the complexity, their capacity to learn is not just hindered— it’s completely out of reach. What I saw as a support aide was not an isolated problem, but a glimpse into the daily struggle carried by countless educators and school counsellors across the province. Every child deserves equity in their learning environment; one curriculum does not fit all. If we truly want children to learn, grow, and thrive, we must evolve our school counselling systems to offer functional mental health support that fosters prevention, and is accessible for all students. Children are highly capable of learning effectively when they have the mental capacity to do so. Strengthening counselling services by reforming the existing structure in public elementary schools is not only feasible, but a critical oversight in our public education system.

High-needs elementary schools experience the most challenging circumstances: the most vulnerable youth attending and the least amount of support in classrooms. Such a condition leaves school counsellors and staff beyond capacity, ultimately failing the children that are expected to develop through these systems. Since students already spend most of their time in school, expanding the counselling division to include more than one full-time school counsellor, and incorporating universally accessible mental-health based programming that fosters prevention, points us in the right direction. Although the BC Government claims that access to mental health is being implemented, the issue in reality still remains challenging. Including stronger mental health systems relieves not only the strain placed on faculty, but on external public mental health clinics that are already at max capacity. Through examining psychological research that calls for such reforms, analyzing how our provinces funding is being distributed and considering the personal experiences of BC counsellors— the solutions we are looking for lay in the details of our systemic structures.

One of many heritage school buildings in East Vancouver, and among the oldest— built and founded in 1909. While full of history and character, the structure also reflects the challenges many older schools face today, particularly when it comes to meeting modern standards for student support and accessibility.

It hollows me to know that there are grade four students attending school in Vancouver who cannot read— in 2025. Not because they lack the intelligence or potential to, but because they were never given the extra support they needed during these critical years of development. This is not the fault of schools themselves—the roots are more intricate than that. It’s the fault of the system that expects these schools to educate and raise our future generation, with less. How much more can we expect from teachers who are already overworked, underpaid, and stretched thin across classrooms of 23 other children? I know this truth because I have been working alongside these teachers and students on a weekly basis since becoming a support aide. I was the witness and listening ear to a second grader’s parental story— he shared how his mother stopped doing drugs “to have him be born” and his father recently died from an overdose. My privilege was in ignorance. In realizing that I had never known a seven-year-old boy who understood and used the word overdose, let alone in the context of his mother and father.

These are not stories to feel sad about, these are realities you cannot dismiss. Children cannot advocate for themselves in the way adults can, nor do they fully grasp how their academic experiences—or the absence of support—may shape their future. Rather than articulating their struggles, children often express distress through behaviour, which can lead to them being labeled as “troubled” or a “bad kid.” These harmful labels obscure reality: many of these children have endured significant hardship without access to the resources they need. As a result, we see young students struggling to engage with learning and function effectively in classroom settings. This is why elementary school is a critical window for implementing preventative mental health support—students are in a highly developmental stage, and early intervention can build resilience and equip them to navigate the challenges ahead.

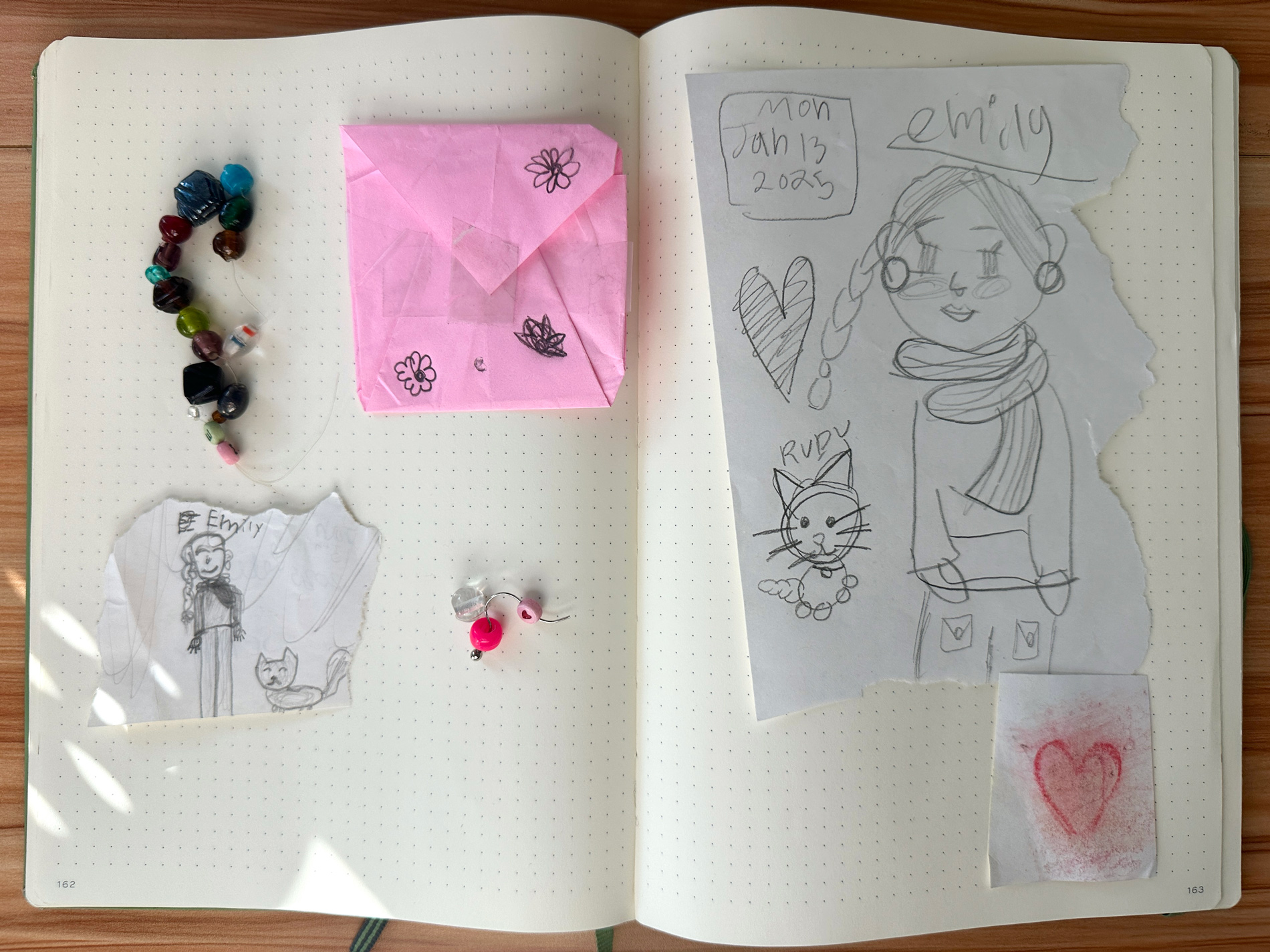

These are handmade gifts from the students I supported during my practicum as a student support aide. Several grade 4 students drew portraits of me and my cat, beaded friendship bracelets, and crafted paper envelopes to hold flowers and small treasures we collected together during recess and after-school care.

“Access to mental health services is a fundamental right of all children,” states Schwartz in her Quarterly article, a publication dedicated to children’s mental health research in Canada. Mental health services are essential services and are as necessary as public schools providing lunch programs. With classrooms becoming increasingly complex due to children dealing with more mental health challenges than ever before, and public mental health clinics seeing an enormous influx of individuals seeking help— growing waitlists are unable to serve every child waiting for their essential service of help. Creating full counselling divisions within our education systems would host registered counselling staff who can assist and teach students about their mental health and practice methods of prevention, all to better prepare our elementary-aged children to flourish and be resilient in their development and ability to learn.

Currently 577,024 students attend public schools across BC, yet the ratio of school counsellors to student population is a striking one counsellor per 693 students. Such a statistic has existed for over 20 years, says the president of the BC School Counsellors Association, Dave Mackenzie who has issued a statement, calling for the Ministry to vocalize the need for change. For a point of reference, the recommended ratio of student to counsellor highlighted by the BC Teacher’s Federation is 250 to 1, and even that number is exceeding capacity. This is a devastating statistic that reflects the harm-causing reality happening to overburdened school counsellors, teachers and staff. All of which fails to remedy and provide essential mental health support for children, trickling down to affect student’s ability to learn during their time in schools. The lack of essential mental health support fails to help mental health disorders that are typically preventable in children during this time of their development.

Children’s mental health research conducted in BC states that “12.7% of children, or approximately one in eight, met diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder at any given time.” In BC, approximately 95,000 young people currently meet criteria for a mental disorder, making the burden high across the province. Even then, many children carry an even higher burden. Specifically, 26.5% of young people with disorders have two or more mental health disorders occurring together. This means about 95,000 children in BC are experiencing mental disorders with symptoms that are severe enough to substantially interfere with their ability to participate at home, at school and in the community.

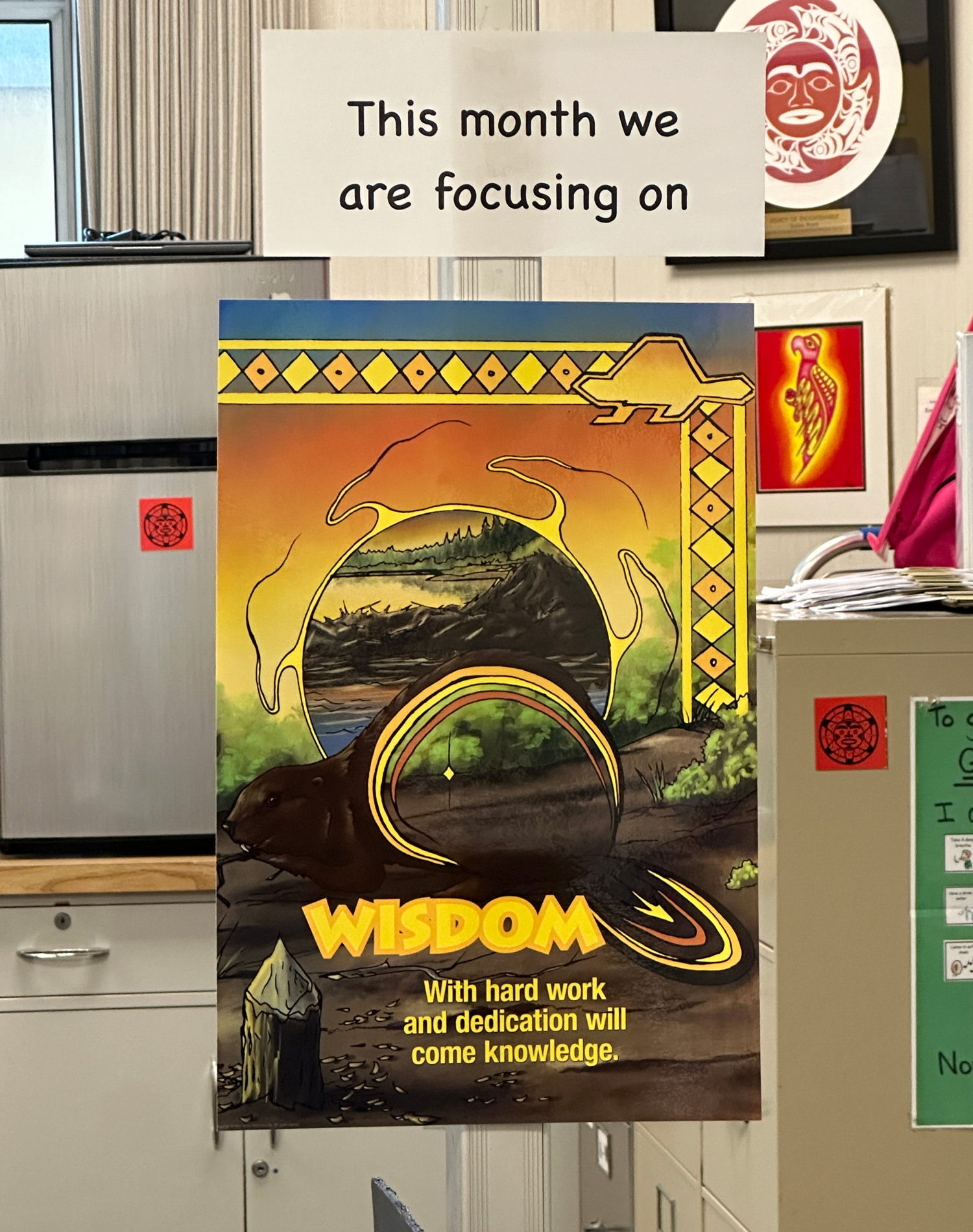

Each month, the school’s office displays a new poster highlighting the theme of that month’s academic focus. In April, the theme was “wisdom”— a fitting reflection of my capstone project, which centres on the need for wisdom in approaching preventative care and mental health support in public elementary schools.

The truth here is that prevention is fully possible and effective and therefore must be worked into our academic structures. Establishing greater systems of mental health support specifically in elementary schools is a high priority. When a child’s development is interrupted by mental disorders, ongoing symptoms of distress and impairment towards academic, cognitive and social learning occurs. This means that children are learning at a significantly lesser capacity that impedes their functionality significantly into adulthood, ultimately causing associated strains and loss in our society.

To enable young students to have a better chance, access to learning about mental health, tools for handling personal challenges and creating internal systems that contribute to prevention are related methods towards students being more proficient in their learning experience. The director of Children’s Health Policy Centre at SFU, Charlotte Waddell has conducted rigorous research towards such a solution. Waddell proposes a universal prevention program to be delivered to entire elementary school populations, accessible to every student in school. Alongside a universal program, targeted prevention programs are also vital for children and families identified as being at risk. The research shows that the use of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) for a variety of mental health disorders, such as anxiety, depression and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, to list a few, are statistically effective. Utilizing CBT strategies would involve educating children and families about anxiety; how to reduce physical symptoms using techniques such as deep breathing, teaching children how to challenge unhelpful and unrealistic anxious thinking, while encouraging them to practice these skills on a daily basis. This study found that CBT was an effective method in preventing symptoms in children aged four to 17 years, affirming that the odds of being diagnosed with an anxiety disorder were more than eight times lower when the participant population received CBT.

Prevention is a considerable thread in the tapestry of developing our school’s counselling systems, as future expenses in healthcare, special education, child protection and justice systems are avoided as a result of investing in preventative measures now. These investments extend into reducing economic losses associated with people’s contributions to society when mental health disorders persist unnecessarily into adulthood. Cohen and Piquero found in their study that early prevention of developing conduct disorders in one child can save society an estimated $5-8 million over that child’s lifetime. Prevention based programs such as Incredible Years produces returns of approximately $9 thousand per child, and the Good Behaviour Game led to returns of $14 thousand per child. All of which is to say that successful prevention programs are effective in preventing disorders and arising symptoms, eventually paying for themselves by reducing their use of external public services over time. Implementing such programs can efficiently happen within schools, with proper funding direction. Through their use, students are not being referred to external health clinics, so they can receive their help at the place they spend most of their time in. Taking the strain off our public mental health services to help those in need outside of the school system.

This hand-made artwork greets you at the front entrance of the elementary school, featuring a vibrant collection of beachside scenes in Vancouver. Students depicted people swimming in the ocean, apple picking, building sandcastles, biking, and swinging. The display captures the brilliant imaginative spirit and creativity of elementary-aged children— a quality that deserves to be continuously nurtured within our education systems.

It is evident that our education systems have been utilized solely for academic and physical health teaching purposes, with little priority placed on an individual’s mental health. The BC gov states in their 2019 document “A Pathway to Hope” that “The neglect of promotion, prevention and early intervention services has contributed to a downward trend in the social and emotional development of young children. After so many years when so little was done, B.C. isn’t prepared or able to provide equitable access to trauma-informed, culturally safe and person-centered care when young people and their families need it.” Today, the BC government has every intention of fostering mental health support strategies within school systems, all of which are neatly stated on paper— projecting their new ideals of “a whole-school system that promotes positive mental health” describing that “wellness promotion and prevention needs to be the focus, starting in the early years and spanning throughout a child’s life.” But the current reality represents a vastly different truth.

In an interview with Bailey Pearson, the only school counsellor at a public elementary school in East Vancouver, we discussed her ten years of experience within the system. Pearson states that, “A lot of my role, is trying to connect to outside community supports. One of the biggest frustrations right now is those systems are all maxed out, consistently having a 12 to 24 month wait list… which is obviously not something a parent wants to hear. On top of that, they’re essentially only able to take on the most extreme cases.” Pearson explained that she works between two schools to fulfill her full-time enrolment requirement, meaning two days at one school, and three days at another. The BC government claims that “schools are an important first step on a pathway of care,” yet reality reflects that this elementary school’s entire population has two days out of the week to access school counselling services— how many children can be effectively helped in that timeframe? Pearson furthered by saying that “A lot of people don’t understand my role includes more than independent work with students, long term consistent counselling is out of the picture because of the system, I can only do more short term solutions— that’s why a lot of my role is trying to refer out families, but it becomes incredibly frustrating when those free public supports are also maxed. It feels like a dead end for families.”

Tucked at the top of a narrow stairwell, the elementary school’s counselling office is small and easy to miss, nearly feeling out-of-the-way in comparison to the rest of the designated spaces. Not pictured is the inside of the tiny space, lovingly decorated by the school’s counsellor with plants and fairy lights. The perfect exemplar of the current state of our mental health resources in public elementary schools.

The reality of school systems failing to have accessible access to mental health support plays a significant role in the mental health crisis that has been rising across Canada— because of how much time children spend at school, our school systems can serve as a platform to better educate, prepare and foster prevention in children by building tools that support their mental health challenges. In 2011, the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) estimates that mental health challenges cost the Canadian economy approximately $50 billion annually. How are these numbers related to children? Schwartz and her team breaks down one portion to this statistic, explaining that “parents may have to miss work to address their children’s mental health needs, or they may face out-of-pocket expenses for medications or for psychosocial interventions that are not publicly funded.” Furthering that “Having a child with a mental disorder can also have considerable consequences for families. For example, one study found that parents of children with mental disorders were significantly more likely to reduce their work hours or to end their employment altogether.” These facts are important, because they contribute to the financial devastation that is a result of poor mental health services in schools. When children do not receive needed treatments, or cannot receive them in a timely way, mental health problems worsen and become needlessly entrenched, often continuing into adulthood. Now these children grow up stifled by unresolved mental health challenges. How are they supposed to function productively in our societal sphere? Where do we go from here?

Australia stands as an example of a high-income country that was able to double the proportion of young people accessing services for mental disorders over a period of approximately 15 years. This process was achieved through increasing funding for mental health services as well as changing how funding was used. For example, Australia decreased spending for psychiatric hospitals, and increased spending for community mental health care — an essential priority for the population. In contrast, it was not until last year that the Canadian government responded with real help. In April 2024, our government proposed a $500 billion dollar Youth Mental Health Fund that began to take effect across the country as of February 20, 2025. The Canadian government expressed that “Young people across Canada are struggling with their mental health. It’s crucial that they have timely access to the right services and supports within their communities. Through the Youth Mental Health Fund, the Government of Canada is making strategic investments to create lasting and meaningful improvements in the mental health of youth and for their families.” So far, over $46 million dollars of funding has gone to six different mental health clinics and service centres across the country. Over time, more and more mental health service centres who applied for funding will receive their portion, which will alleviate waitlists to access such help. Knowing that funding is available, how does this magnitude of financial aid reach the school districts to reform the system into one of better help?

Public schools receive their funding directly through the provincial government and BC’s 60 elected Boards of Education— all of which annually establish the amount of grant funding for public education. A funding formula is used to allocate these funds into the Boards of Education, where management and allotment of these funds is distributed based on local spending priority, adding that “special programs” can be accessed through supplemental government funds. The use of the term, “special programs” in the BC Gov website refers to Behaviour Support Programs that provide extra support for student’s social development. The terminology used is an illusion to cover the dead-end reality— such behaviour support programs are not universally offered or accessible across public elementary schools. How can families living in a catchment that does not offer these programs gather help when their school counsellor cannot refer them to full public mental health clinics? All questions trickle down to one common denominator.

Public schools notoriously struggle to balance their budgets. According to Statistics Canada, BC now allocates less of its Gross Provincial Product (GPP) toward its public schools than any province except Newfoundland and Labrador. This means that a smaller percentage of funding is available for students in BC school boards, failing to access newer public infrastructure, classroom supplies and books, to name a few aspects. Public schools are a provincial responsibility, and are struggling to support their student population, especially students with mental health and learning challenges. VSB trustee Jennifer Reddy stated that current funding for school supplies is lower than what the district allocated in 2010. To add, there is a major discrepancy between how provincial funding reaches public and private schools in the province. This comparison is relevant because in BC, the public directly subsidizes private schools, a staggering $570 million dollars in annual operating grants. Meaning, when private schools accept students with higher learning needs, the school can claim 100% of the supplementary provincial grants meant to support those same needs in public schools. Meanwhile, low-income families who can’t afford private education are left behind, their children going without support, while their tax dollars help subsidize the care of those who already have access to private resources. It’s a system that gives more to those who already have, and less to those who need it most.

Through understanding the past context of how funding and expenditure has been received by public school systems, we can understand how students are affected. Policy changes are long overdue, but luckily, as of November 21, 2024, BC Gov claims that “money allocated for the new priority student supplement will be provided to school boards to deliver services based on local needs and is intended for supports like trauma counselling,” while also ensuring that “more than $6 billion in operating funding is distributed in a way that better represents the number of vulnerable students in BC schools.” Much work needs to be done fundamentally, and the research is clear— our schools are in urgent need of stronger mental health systems. Real change will require the provincial government and all 60 Boards of Education to come together, acknowledge the long-standing evidence, and listen to those working directly with students. Only then can we begin to build a system where the next generation has the support they need to truly grow and thrive.

The mental health crisis that involves children across Canada is not a distant nor abstract concern— it continues to permeate our public elementary schools. Political plans and progress are boasted, but the lived experiences of school counsellors, students, teachers and families reveal a majorly different story— one defined by underfunding, crippling waitlists and complex systemic barriers. Schools, the place where children spend most of their time, are life-changing platforms, yet they remain the most under-utilized system for early intervention and prevention of mental health challenges. The thorough evidence that supports the effectiveness of mental health care for children demands such changes to be made. With prevention programs that include CBT methods, and with funding beginning to emerge at the federal level, the need to act has never been more dire. A redeveloped system of education that understands the value and role of mental wellbeing for children’s academic success and future functionality is not only possible but critically essential. Ensuring properly funded, comprehensive and accessible mental health services in public elementary schools must be understood as an urgent priority for the province. Effective learning can only occur when mental capacities that are not overloaded with challenges, every child deserves this foundation and support throughout their academic experience. Anything less is not only neglect, but a betrayal of the very future we claim to care so deeply about.

References

Schwartz, Christine, et al. “The high burden associated with childhood mental disorders.” Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 3-5. https://childhealthpolicy.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/RQ-16-22-Spring.pdf.

Schwartz, Christine, et al. “How well are treatment needs being met?” Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 6-11. https://childhealthpolicy.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/RQ-16-22-Spring.pdf.

Mackenzie, Dave. “BC’s MHiS Strategy & School Counsellors.” BC Counsellor, vol 1. Spring/Summer 2022, https://www.bccounsellor-digital.com/bcot/0122_spring_summer_2022/MobilePagedArticle.action?articleId=1775872#articleId1775872.

Olsen, Adam. “Our Children Need Help— When will the BC NDP Hire Enough Counsellors to Meet the Needs of Students?” Adam Olsen, 4 April. 2023, https://adamolsen.ca/2023/04/our-children-need-help-when-will-the-bc-ndp-hire-enough-counsellors-to-meet-the-needs-of-students/.

Schwartz, Christine, et al. “Preventing and Treating Childhood mental Disorders: Effective Interventions.” Children’s health Policy Centre, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 4-22. https://childhealthpolicy.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/CHPC-Effective-Interventions-Report-2020.10.25.pdf.

E Pella, Jeffery, et al. “Child Anxiety Prevention Study: Impact on Functional Outcomes.” Child psychiatry and human development, vol. 48, no. 3, 2017, pp. 400-410. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27392728/.

Cohen, M. A., & Piquero, A. R. (2009). “New evidence on the monetary value of saving a high risk youth.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 25–49. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-03045-002.

Washington State Institute for Public Policy. Benefit-Cost Results for Good Behaviour Game. Washington State Institute for Public Policy, December 2024, https://www.wsipp.wa.gov/benefitcost.

BC Centre for Mental Health and Addictions. “A Pathway to Hope: A roadmap for making mental health and addictions care better for people in British Columbia.” gov.bc.ca, 2019, https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/british-columbians-our-governments/initiatives-plans-strategies/mental-health-and-addictions-strategy/bcmentalhealthroadmap_2019web-5.pdf.

BC Ministry of Education. “Mental Health in Schools Strategy.” gov.bc.ca, 2020, https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/erase/documents/mental-health-wellness/mhis-strategy.pdf.

Pearson, Bailey. Personal Interview. 25 February, 2025.

Mental Health Commission of Canada. “Making the Case for Investing in Mental Health in Canada.” Mental Health Commission of Canada, June 2016, https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/drupal/2016-06/Investing_in_Mental_Health_FINAL_Version_ENG.pdf.

Lawrence, David, et al. “The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing.” Department of Health, 2015, https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/11/the-mental-health-of-children-and-adolescents_0.pdf.

Health Canada. “Government of Canada spotlights first community-based projects to spearhead Canada’s largest investment in improving youth mental health.” Canada.ca, Feb 20, 2025, https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2025/02/government-of-canada-spotlights-first-community-based-projects-to-spearhead-canadas-largest-investment-in-improving-youth-mental-health.html.

Government of British Columbia. “K-12 Funding and Allocation.” gov.bc.ca, Dec 16, 2024. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/k-12/administration/resource-management/k-12-funding-and-allocation.

Vancouver School Board, “Behaviour Support Programs.” Vancouver School Board, https://www.vsb.bc.ca/page/38037/behaviour-support-programs.

Hyslop, Katie. “Enrolment is Up. Why Are BC Schools Still Facing Budget Cuts?” The Tyee, June 13, 2024. https://thetyee.ca/News/2024/06/13/Enrolment-Up-BC-Schools-Budget-Cuts/.

Bacchus, Patti. “Increased public funding for private schools is diving us, and needs to stop.” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, Feb 5, 2025, https://www.policyalternatives.ca/news-research/increased-public-funding-for-private-schools-is-dividing-us-and-needs-to-stop/.

Hemingway, Alex. “What’s the real story behind BC’s education funding crisis?” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, August 2016, https://www.policyalternatives.ca/wp-content/uploads/attachments/ccpa-bc_Kto12EducationFunding_web.pdf.

Statistics Canada. “Public and private expenditure on educational institutions as a percentage of GDP, by level of education.” Statistics Canada, Oct 22, 2024, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710021101.

Government of British Columbia. “K-12 Public Education Funding Model Implementation.”gov.bc.ca, Nov 21, 2024. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/k-12/administration/resource-management/k-12-funding-and-allocation/funding-model.