Meagan McAuley

My name is Shona Meagan McAuley, though I go by Meagan. I’m a fourth-year Psychology major at Capilano University, and as a 33-year-old mature student, I bring a unique perspective and deep sense of purpose to my studies. My ultimate goal is to become an elementary school teacher, where I can help build more inclusive, supportive, and engaging classrooms for the next generation.

Born at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, I spent most of my early life in Richmond before returning to the city four years ago. My partner and I now live in the West End, where we’re surrounded by nature, culture, and a vibrant sense of community. I work part-time at a local community centre, where I support children in after-school programs – an experience that continues to strengthen my passion for teaching and youth development.

Outside of school and work, I live a very active lifestyle and feel most at home in nature. Whether I’m running along the seawall, hiking in the North Shore mountains, or walking through Stanley Park, I find immense joy and peace in the outdoors. I share most of these adventures with my one-and-a-half-year-old Golden Retriever, Bella, who keeps me on my toes and brings endless joy to my daily life.

I also love baking, and making cookies has become a bit of a signature hobby – one that I often share with friends and family. Life in Vancouver offers the perfect balance of activity, beauty, and inspiration. As I continue this chapter of academic and personal growth, I’m excited about where this journey will take me – and how I can one day contribute meaningfully to the lives of young learners.

Canadian elementary schools have an opportunity to improve student well-being, academic outcomes, and teacher effectiveness by learning from the education systems of Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Iceland. These Nordic countries routinely exhibit higher student well-being, stronger academic outcomes, and more effective teacher training compared to Canada. My investigation will examine the key policies and systemic approaches that drive the Nordic success and explore how Canada can adapt and implement these strategies to create a more equitable, high-performing elementary education system.

Quantifiable differences in student achievement highlight Canada’s opportunity to improve. Nordic countries consistently demonstrate stronger student achievement and equity in education compared to Canada. According to the latest data from Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), all participating Nordic nations outperformed Canada in both Grade four mathematics and science – with results that were statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (von Davier et al., 2024). These countries also show impressive levels of upward educational mobility. In Finland and Sweden, “30% of adults whose parents did not attain upper secondary education have completed tertiary education” (OECD, 2024a, p. 52). Additionally, “the highest levels of government expenditure – at least 5% of GDP – are found in several Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden)” (OECD, 2024a, p. 276). These outcomes suggest that the Nordic approach is not only more equitable but also more effective, offering a valuable model for Canadian reform.

My interest in elementary education reform comes from both personal experience and professional exposure. I grew up in Richmond, BC, and my own education felt inadequate and lacking support. My classes were too full, my schools lacked resources, and my parents had to pay for private tutoring just to get me to an expected reading and math level. I spent four years at Sylvan Learning, where I learned exponentially more in a shorter time because of the personalized instruction and highly engaged teachers. Now, after five years working with children, I see that many of the same problems persist – low reading levels amongst those with non-traditional learning styles and from less privileged families, stressed teachers, understaffed schools, and a lack of resources for students who need extra support.

I spent three years working in the Richmond School District as an administrative assistant and two years as an out-of-school care provider at the West End Community Centre, where I worked closely with children, parents, and teachers. This gave me firsthand insight into how overburdened the school system is and how many students are falling behind. As I pursue my degree in Psychology at Capilano University, my ultimate goal is to become an elementary school teacher and contribute to meaningful improvements in the education system. Recently, my partner was offered two job opportunities in Finland, which led me to research Nordic education systems. Since we are thinking about starting a family soon, I began looking into how schools in Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Iceland compare to those in Canada. What I found was a well-balanced, student-centered approach that prioritizes small class sizes, teacher autonomy, outdoor learning, and life skills education. This essay was born out of a personal desire to understand what Canada can learn from Nordic countries and how we can create a better, more accountable education system for future generations.

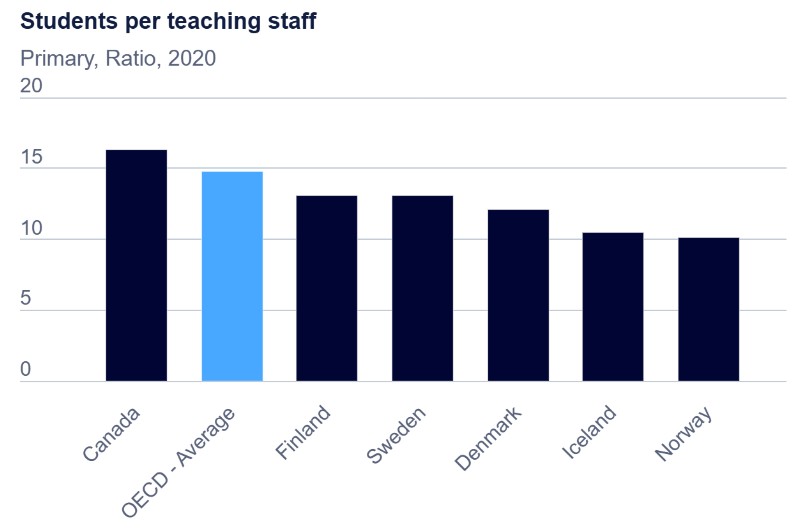

Canada has a higher student to teacher ratio at the primary level than all of the Nordic countries (OECD, 2024b).

Education systems worldwide vary in how they approach funding, class sizes, teacher autonomy, curriculum flexibility, and student well-being. Canada’s elementary schools operate within a publicly funded system, where education policy and funding differ by province and territory. In contrast, Nordic countries implement funding models that are often structured around student enrollment rather than fixed allocations to schools, creating a more direct link between funding and student needs (OECD, 2024a). These countries have also gained recognition for prioritizing small class sizes, teacher training, and student well-being. As Canada continues to address challenges related to class sizes, teacher burnout, school autonomy, and inequality, examining alternative education models from Nordic countries could provide valuable insights for improving student outcomes and overall system efficiency.

Ten Key Reforms Across Four Categories

To improve student outcomes and build a more equitable elementary education system, I propose ten key reforms, organized into four categories: curricular, systemic funding, teacher training, and school programming. These reforms draw directly from successful practices in Nordic countries and reflect both research and my own lived experience within the Canadian education system. The curricular reforms focus on smaller class sizes with more individualized support, increased outdoor play and nature-based learning, and the integration of practical life skills into the curriculum – approaches that support both academic development and student well-being. The systemic funding reforms call for both a greater overall investment in public education and a shift in how that funding is allocated. Education is one of the most essential responsibilities of provincial governments in Canada (alongside healthcare), and it deserves a level of funding that allows for sustainable student-teacher ratios and adequate resources across all schools. In addition to enhancing the total funding, I propose adopting a funding-follows-the-student model, where resources are tied to student enrollment rather than assigned directly to schools. While this model may be viewed as controversial by some, I will argue that – when implemented thoughtfully – it ensures schools remain motivated to meet high standards and serve students effectively. In the area of teacher training, I recommend raising qualification standards and improving the relevance of teacher education programs, ensuring that future educators are not only knowledgeable but also prepared for the deeply social nature of teaching. Finally, school programming reforms emphasize greater teacher autonomy, flexible school structures, and cost-covered nutritious meals for all students.

With increasing student needs and mounting pressures on educators, these reforms are not just idealistic – they are necessary. The following sections will unpack how each proposal, inspired by proven Nordic strategies, can help transform Canadian classrooms into environments where all children have the opportunity to thrive.

The entrance to the “Lunch Lab” at Lord Roberts Elementary, with taped signage indicating the location – a small detail that highlights the improvised and resource-limited environments many Canadian students navigate daily.

Curricular Reforms

Strong curriculum design is foundational to effective education. In Nordic countries, thoughtful curricular structures support not only academic success but also the development of the whole child – socially, emotionally, and physically. In Canada, however, the content and structure of the elementary school curriculum often fails to meet students where they are. Too many classrooms are overcrowded, rigid, and disconnected from the realities of children’s developmental needs. When I was a student in Richmond, my elementary classes regularly had more than 25 students to one teacher. There was rarely time for teachers to support us individually, and I often felt lost in the crowd. Today, after working closely with both children and educators (and also having friends in these fields), I know this challenge persists. Teachers continue to struggle under the weight of oversized classes and insufficient support. A shift toward smaller class sizes – already a standard in Nordic countries – is one of the most pressing and actionable reforms Canada can pursue. Nordic countries maintain lower student-to-teacher ratios, allowing for more personalized instruction and better academic outcomes (OECD, 2024b). This is supported by experimental research out of Tennessee, which found that students placed in small classes from kindergarten through grade three showed significantly higher achievement in reading, math, and science, with effects lasting at least through grade eight (Nye et al., 1999). Smaller class sizes do not simply improve test scores – they make learning more human, more relational, and more responsive to individual needs. This is echoed by my grandfather, Seamus McAuley, a retired BC teacher of over three decades, who shared: “Smaller class sizes have been the single biggest factor throughout my career that have led to improved student/teacher relationships and interactions, classroom management, student focus, and overall achievement” (S. McAuley, personal communication, March 3, 2025).

Alongside class size, the learning environment itself matters. Sitting inside for six hours a day, especially when the weather was beautiful, felt unnatural and exhausting when I was a child. I remember looking longingly out the window, wishing we could learn outside, or even just move our bodies. Yet, our curriculum was confined to the classroom. Nordic countries take a different approach. Nordic schools emphasize outdoor education and unstructured play, recognizing that physical movement, exposure to nature, and variety in learning environments all contribute to better outcomes. Studies involving Danish and Finnish primary students found that outdoor education significantly increased physical activity levels, contributing to healthier routines during the school day (Bølling et al., 2021; Romar et al., 2019). In addition, outdoor learning improves students’ social behavior, with children who regularly participate in outdoor classes demonstrating stronger peer collaboration and social interaction (Bølling et al., 2019). These aren’t simply added perks – they are core components of a curriculum that values children as whole human beings. Outdoor learning helps foster attention, emotional regulation, and interpersonal skills, all of which are essential for long-term development.

Children’s chalk drawings outside Lord Roberts Elementary reflect imagination, emotional expression, and the kind of spontaneous outdoor creativity that supports whole-child development – a core emphasis in Nordic education systems.

In addition, the Canadian curriculum must be updated to better prepare students for real life. In my entire elementary and secondary education, I was rarely taught how to cook and never learned how to build a budget, write a resume, or file taxes. School was framed as a pipeline to university, but it failed to equip me with the life skills necessary for independent living. In contrast, Nordic schools emphasize real-world skills like financial literacy, problem-solving, and hands-on trades, preparing students for independent living and future careers (Kirchhoff & Keller, 2021). These life skills, such as persistence and self-control, developed in early grades have been linked to faster growth in reading achievement (Chien et al., 2012), while also enhancing emotional regulation, decision-making, and positive social relationships (Kirchhoff & Keller, 2021). Additionally, social skills programs benefit students, reduce teacher stress, and improve classroom learning environments (Smolkowski et al., 2022). These types of skills are the foundation of a functional, capable, and adaptable society. A reimagined Canadian curriculum should prioritize these abilities early and intentionally.

By reforming curriculum through smaller class sizes, outdoor learning, and meaningful life skills instruction, Canada can better serve the diverse and evolving needs of its elementary school students. These changes are not radical. They are proven, practical, and long overdue.

Systemic Funding Reforms

Improving Canadian elementary education demands a reevaluation of how schools are funded. While increased investment is critical, how that money is distributed matters just as much. In Canada, school funding is often tied to fixed allocations rather than student needs or enrollment, leading to inefficiency and little incentive for improvement. It is time for Canadian provinces to adopt a funding model where funding follows the student – a system designed to empower families, increase accountability, and enhance outcomes through healthy competition.

There is little debate around the first point: schools need more funding. Decades of underinvestment have led to overcrowded classrooms, insufficient support staff, outdated infrastructure, and inadequate mental health resources. These issues cannot be resolved without a significant increase in overall education funding at the provincial level. Sustainable student-teacher ratios, targeted programs for students with disabilities, and modernized facilities require real financial backing. However, without reforming how that funding is distributed, even additional investment may fail to generate meaningful change.

Currently, most Canadian public schools operate essentially as a monopoly – they are the only truly accessible option for most families. Students are typically assigned to a school based on their geographic location, and that school receives funding regardless of its outcomes, efficiency, or responsiveness. In this model, there is no meaningful competition and very little incentive for schools to improve their services. As Hanushek and Rivkin (2003) explain, lack of competition in public schooling can result in complacency and decreased school performance. Hoxby (2000) similarly warns that when public school systems act as economic monopolies, it reduces accountability and responsiveness to the needs of both parents and students. When funding is guaranteed and schools face no pressure to attract or retain students, the result is a stagnating system with few mechanisms for course correction. As Chubb and Moe (1990) argue, public school monopolies can lead to inefficiencies and lack of innovation, negatively impacting student outcomes.

A funding model where money follows the student would reverse this dynamic. Instead of schools receiving fixed funds simply for existing, they would receive funding based on how many students they serve, the types of students they serve, and how well they serve them. Under this model, all parents would receive a government-funded voucher representing the per-student funding value, which they could “spend” at any accredited public (or non-profit independent) school of their choice. Importantly, this model can and should be designed with equity in mind: students with special needs or learning differences should carry higher-value vouchers, recognizing the increased resources required for inclusive education. As a concrete example, a non-verbal autistic student would carry a significantly higher voucher valuation than a neurotypical student – since the autistic student requires 1-to-1 support. This student-centered funding model promotes transparency, aligns school incentives with student outcomes, and allows families to choose the learning environment that best fits their child.

The historic exterior of Lord Roberts Elementary School in Vancouver, built in 1907 – a reminder of the aging infrastructure in many Canadian public schools and the pressing need for modern, well-resourced learning environments.

There is robust empirical evidence supporting this approach. In the United States, the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program (MPCP) led to modest improvements in public elementary school performance due to increased competition, prompting public schools to implement reforms to retain students (Hoxby, 2003). A broader systematic review of 92 studies found that competition from school choice programs improved standardized test scores for both students who utilized vouchers and those who remained in public schools (Jabbar et al., 2022). In Sweden – one of the few countries with a nationwide school voucher program – research has consistently shown that increased competition from independent schools has led to positive effects on student achievement in both public and private schools (Ahlin, 2003; Sandström & Bergström, 2005; Böhlmark & Lindahl, 2007).

Critics of voucher systems often express concerns about equity or privatization, but these issues are addressable through careful policy design. Public schools can remain tuition-free and non-profit, accepting vouchers at face value and reinvesting any surplus funding into infrastructure, programming, and student services. Private schools may still operate outside the voucher system, but their participation would not be subsidized by public funds – helping prevent tuition inflation and safeguarding access for all families. What matters most is ensuring that schools are held accountable and must earn the trust and enrollment of families, rather than relying on a guaranteed stream of funding. When schools compete, students win.

Teachers can end up better off as well. In a funding-follows-the-student model, educators who deliver meaningful, engaging, and high-quality instruction will be in higher demand. As students gravitate toward schools that offer better learning environments, those schools can reward top-performing teachers with better compensation, greater autonomy, and expanded professional opportunities. Rather than being stuck in underperforming institutions with little incentive to innovate, great teachers will thrive in systems that recognize and reward their contributions.

By shifting toward a funding model that prioritizes students – not institutions – Canada can reinvigorate its public education system and align incentives around what truly matters: the success of our students, the empowerment of our educators, and the development of future generations.

An outdoor basketball hoop in the Lord Roberts Elementary schoolyard, with a worn backboard and frayed net – a subtle reminder of the limited recreational resources found in many public school environments.

Teacher Training Reforms

Of course, even the most well-funded and accountable school system depends on the quality of its teachers. No investment in infrastructure or policy will make a lasting difference if teachers are not properly prepared to meet the real-world demands of today’s classrooms. Unfortunately, teacher education in Canada is often underwhelming – both in terms of academic rigor and practical relevance. In most provinces, becoming a teacher requires a general undergraduate degree, followed by a one-year or two-year education program and provincial certification. While this path is well-intentioned, it leaves many new educators feeling unprepared. I know several friends who entered teaching programs with little to no experience working with children, and they were shocked at how overwhelming and unpredictable the actual classroom environment was. Many told me they felt unqualified for the role, even after completing their educational training. As my grandfather, with his over three decades of teaching experience, explained, “You could make a strong case that any academic degree is the wrong instrument for evaluating the quality of education in BC, or anywhere else. Why? Because there is very little correlation between having a master’s degree and having the ability to teach” (S. McAuley, personal communication, March 3, 2025). From my own experience working with children in out-of-school care and in the public school system, I know firsthand that managing a classroom is not something that can be learned in theory alone – it takes extensive practice, emotional intelligence, and hands-on mentorship. I vividly remember my first day working at a day camp, where I became so overwhelmed that I cried in the bathroom. Over time, I improved and grew to love the work. However, working with children is not for everyone – it requires resilience, empathy, adaptability, and a great deal of patience.

Finland, by contrast, has reimagined what it means to be a professional educator. All Finnish elementary school teachers are required to complete a master’s degree in education, and admission to teacher training programs is highly selective. This is not a matter of adding more schooling for its own sake; it is about ensuring that education is relevant to the job. Finnish teacher education programs emphasize communication, psychology, classroom research, and lean heavily on practicum teaching experiences (Chung, 2023). The training is deeply rooted in understanding how children learn, how to foster emotional well-being, and how to create an inclusive and responsive classroom. Teachers are viewed as highly trained professionals, comparable in prestige to doctors or lawyers (Sahlberg, 2012).

Canada must move toward a model that respects the complexity of teaching by raising qualification standards and aligning training with the social, emotional, and developmental realities of the classroom. The future of our students depends not just on having teachers – but on having teachers who are truly prepared to lead, inspire, and support.

School Programming Reforms

A great school system is not just defined by what is taught, but by how it supports both the teacher and the child. As someone preparing to enter the teaching profession, I often think about what kind of environment would allow me to thrive and help my students do the same. It would be one where I am trusted to adapt to the specific needs of my class – where I can use my judgment and creativity to make learning meaningful. In Finland, this is the norm. Finnish teachers have the freedom to choose their own textbooks and design lessons tailored to their students’ needs, with the national core curriculum serving as a flexible framework rather than a strict directive (Nguyen, 2019). With higher trust and fewer standardized tests, Finnish teachers have more freedom to design their lessons (Hancock, 2011). Finland emphasizes teacher autonomy, deep subject knowledge, and educational research (Chung, 2023). Crucially, the government exerts minimal influence over Finnish teachers, allowing them to plan teaching independently without mandatory written lesson plans (Maaranen & Afdal, 2022). This autonomy creates a culture of professionalism and trust – one that Canada can learn from.

An empty swing set on the playground at Lord Roberts Annex, a K-3 elementary school located in Vancouver’s West End.

In addition to greater autonomy, Nordic schools are known for their flexible structures. Students in Finland and Sweden have longer recesses, more outdoor time, and flexible scheduling that supports both focus and creativity. This is a philosophy that acknowledges children as dynamic, active learners. As someone who remembers struggling to sit still during long school days, I believe Canadian schools could benefit from this same flexibility. If I have a class that learns better outside or needs movement breaks to stay focused, I want the freedom to build that into my teaching practice. As my grandfather insightfully put it, “Flexibility within a structured teaching environment provides students with diverse learning styles the opportunity to showcase their abilities based on their strengths rather than a strict set of criteria” (S. McAuley, personal communication, March 3, 2025).

Finally, we cannot talk about programming without addressing nutrition. During my time working in schools and after-school programs, I have seen many children arrive without lunch or snacks – often due to family income constraints, but sometimes simply because parents were busy and forgot. When I asked my grandfather if he regularly witnessed children arriving at school without anything to eat and struggling with food insecurity, his response was simply, “Unfortunately, far too often” (S. McAuley, personal communication, March 3, 2025). In Finland and Sweden, nutritious school meals are provided to all students and funded through government tax revenue. There is no stigma and no added cost to families. Canada should follow suit. A cost-covered meal program would reduce food insecurity, improve student health, and allow all children to focus on learning – not hunger.

Conclusion

Canada’s elementary education system is underperforming – but it doesn’t have to be. Drawing inspiration from the proven success of Nordic countries, we can implement ten actionable reforms across four key categories: Curricular improvements like smaller class sizes, outdoor learning, and life skills; systemic funding reforms that increase both investment and accountability; teacher training that raises standards and emphasizes real-world preparation; and school programming reforms that support teacher autonomy, flexible learning environments, and provide all students with nutritious meals at no additional cost. These changes are not radical – they are evidence-based, attainable, and long overdue. Our children deserve better than overcrowded classrooms, outdated funding models, and underprepared teachers. If we truly value education as a foundation for a strong, equitable society, we must act now. The path forward is clear. What remains is the courage and political will to pursue it. By learning from the Nordic example, Canada can build a school system where every teacher is empowered and every child has the opportunity to thrive.

References

Ahlin, Å. (2003). Does school competition matter? Effects of a large-scale school choice reform on student performance (Working Paper No. 2003:2). Uppsala University, Department of Economics.

Böhlmark, A., & Lindahl, M. (2007). The impact of school choice on pupil achievement, segregation and costs: Swedish evidence (IZA Discussion Paper No. 2786). Institute of Labor Economics (IZA). https://docs.iza.org/dp2786.pdf

Bølling, M., Niclasen, J., Bentsen, P., & Nielsen, G. (2019). Association of education outside the classroom and pupils’ psychosocial well-being: Results from a school year implementation. Journal of School Health, 89(3), 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12730

Bølling, M., Mygind, E., Mygind, L., Bentsen, P., & Elsborg, P. (2021). The association between education outside the classroom and physical activity: Differences attributable to the type of space?. Children, 8(6), 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060486

Chien, N., Harbin, V., Goldhagen, S., Lippman, L., & Walker, K. E. (2012). Encouraging the development of key life skills in elementary school-age children: A literature review and recommendations to the Tauck Family Foundation. Child Trends, 28, 1-11.

Chubb, J. E., & Moe, T. M. (2011). Politics, markets, and America’s schools. Brookings Institution Press.

Chung, J. (2023). informed teacher education, teacher autonomy and teacher agency: the example of Finland. London review of education, 21(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.14324/LRE.21.1.13

Hancock, L. (2011). Why Are Finland’s Schools Successful? Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/why-are-finlands-schools-successful-49859555/

Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2003). Does Public School Competition Affect Teacher Quality?‖ in The Economics of School Choice, Caroline M. Hoxby ed.

Hoxby, C. M. (2000). Does competition among public schools benefit students and taxpayers? American Economic Review, 90(5), 1209–1238. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.5.1209

Hoxby, C. M. (2003). School choice and school productivity: Could school choice be a tide that lifts all boats? In C. M. Hoxby (Ed.), The economics of school choice (pp. 287–342). University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/9780226355344-011

Jabbar, H., Holme, J. J., LeClair, A., Sanchez, J., & Torres, E. M. (2022). The competitive effects of school choice on student achievement: A systematic review. Educational Policy, 36(2), 247–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904819874756

Kirchhoff, E., & Keller, R. (2021). Age-specific life skills education in school: A systematic review. Frontiers in Education, 6, 660878. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.660878

Maaranen, K., & Afdal, H. W. (2022). Exploring teachers’ professional space using the cases of Finland, Norway and the US. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 66(1), 134-149. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1851760

Nguyen, T. H. D. (2019). Teacher Autonomy in Finnish Primary Schools: An Exploratory Study About Class Teachers’ Perceptions. Teacher Education. https://trepo.tuni.fi/handle/10024/117232

Nye, B., Hedges, L. V., & Konstantopoulos, S. (1999). The long-term effects of small classes: A five-year follow-up of the Tennessee class size experiment. Educational evaluation and policy analysis, 21(2), 127-142. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737021002127

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2024a). Education at a glance 2024: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/c00cad36-en

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2024b). Students per teaching staff (PISA data dashboard). OECD. https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/students-per-teaching-staff.html

Peralta, L. R., Dudley, D. A., & Cotton, W. G. (2016). Teaching healthy eating to elementary school students: a scoping review of nutrition education resources. Journal of School Health, 86(5), 334-345. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12382

Romar, J.-E., Enqvist, I., Kulmala, J., Kallio, J., & Tammelin, T. (2019). Physical activity and sedentary behaviour during outdoor learning and traditional indoor school days among Finnish primary school students. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 19(1), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2018.1488594

Sahlberg, P. (2012). Teachers as Leaders in Finland. ASCD. https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/teachers-as-leaders-in-finland

Sandström, F. M., & Bergström, F. (2005). School vouchers in practice: Competition will not hurt you. Journal of Public Economics, 89(2–3), 351–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.05.001

Smolkowski, K., Walker, H., Marquez, B., Kosty, D., Vincent, C., Black, C., … & Strycker, L. A. (2022). Evaluation of a social skills program for early elementary students: We Have Skills. Journal of research on educational effectiveness, 15(4), 717-747. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2022.2037798

von Davier, M., Kennedy, A., Reynolds, K., Fishbein, B., Khorramdel, L., Aldrich, C., Bookbinder, A., Bezirhan, U., & Yin, L. (2024). TIMSS 2023 international results in mathematics and science. Boston College, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center. https://doi.org/10.6017/lse.tpisc.timss.rs6460

Beautifully written, logically constructed, thoroughly researched, science based, and 100% “On Target!”

Congratulations Meagan.

Beautifully written, logically constructed, thoroughly researched, science based, and 100% “On Target!”

Congratulations Meagan.

Beautifully written, logically constructed, thoroughly researched, science based, and 100% “On Target!”

Congratulations Meagan.