Ngoc Lam

My name is Ngoc Ngan Lam and I am a fourth-year student graduating with a Bachelor of Science, concentrating in both Biomedical and Computational Sciences. Originally from Vietnam, I completed a degree in Hospitality and Tourism Management before immigrating to Canada in 2015. I have continued my academic journey since then, earning Diplomas in General Arts and Science from Langara College and Opticianry from Douglas College. Currently, I work at IRIS Optometrists and Opticians, where I have had the opportunity to develop invaluable skills in patient care and clinic operations. This experience has deepened my passion for helping people improve their vision and eye health.

With an interest in the field of optometry, my recent biomedical research in Capilano University explores the link between hand hygiene compliance in contact lens wearers and microbial contamination, highlighting the importance of proper handwashing to reduce the risk of corneal complications. I hope this work serves as a meaningful foundation for my prospective studies and research in optometry. Through my computational science concentration, I have explored data analysis, machine learning, and computing technologies such as generative AI. This exposure has led me to question whether AI can ever truly replace humans in both scientific and creative fields such as art. I do not consider science only as a method of discovery, but also a creative process that requires scientists’ curiosity, imagination, and divergent thinking to answer for unknown experimental outcomes.

With this interdisciplinary academic background, I am particularly interested in exploring how humans can utilize AI as a powerful tool to enhance healthcare services. Specifically, I am curious to explore how to integrate AI into the development of advanced medical devices, such as smart contact lenses that can not only correct vision correction, but also monitor intraocular pressure, deliver medications, or collect real-time biometric data.

The launch in 2023 of ChatGPT—an artificial intelligence (AI) model that outperforms humans in a variety of tasks—has challenged many people around the world regarding whether their jobs will soon be replaced by this new type of technology. With AI being implicated in many areas of human life in the past few years, creative fields like art are not an exception to this technology, which grants any individual ability to use generative AI (GenAI) tools to generate aesthetically pleasing art. However, products of AI art generators are among the debates of the public around the world. A survey showed that 76% of participants did not think content created by using AI can be qualified as art (KOAA).

Despite the public’s disapproval towards products created by GenAI, the market for AI art generators is lucrative. A study by Grand View Research showed that in 2023, the profit from the market of the GenAI art tools was $349.6 million globally. Also, a 2024 report which surveyed 300 business leaders in the U.S. predicted that over the next three years, a variety of existing job roles in creative fields are going to be either consolidated or replaced by generative AI (CVL Economics 8). This trend of human creative workers being replaced by a booming generative technology hints that many people, including these business leaders, might not be aware that generative AI has to be continually fueled and trained by huge amounts of human material like intelligence, skills, and creativity. GenAI, specifically AI art generators, would not ever exist without being trained by “human data. “In this article, I will look into why GenAI art tools might not fully replace human artists, since GenAI-made arts lack human perspectives, originality and authenticity, as well as the legal copyrights of human-made artwork.

Immigrating to an ethnically and culturally heterogeneous country like Canada has given me the opportunity to meet and make friends with people from different backgrounds. Being a science student who mostly studies things like formulas, numbers, and theories, meeting individuals working in creative fields like artists, animators, and 3D modelers is a refreshing experience. Admiring my friends’ creativity and skills in animation and drawing, I learned of their concerns about the rise of GenAI use in the creation of digital artwork. Many of these young artists are either having a hard time to be hired by businesses in the field or are afraid of losing their current jobs to the GenAI technology in the near future.

I believe the struggle to be employed in the art-related field is even more prominent in Canada, where we have much less big businesses compared to the U.S. or other countries. I am aware that this struggle that my friends are facing would not be limited to the field of arts, but might also relate to individuals working in other fields where business owners and leaders want to replace humans with GenAI to maximize productivity and lower their expenses. In an interview with Robin Lee, a freelance artist, she expresses how they have had hard time locating a job in the artistry field in Vancouver and is now making her living out of commissions of her digital drawings. The interview gave me a deeper insight into what she thinks and feels about the pervasiveness of GenAI, regarding the reality that she and many of her classmates face upon graduating from BCIT’s 3D Modelling, Art and Animation program.

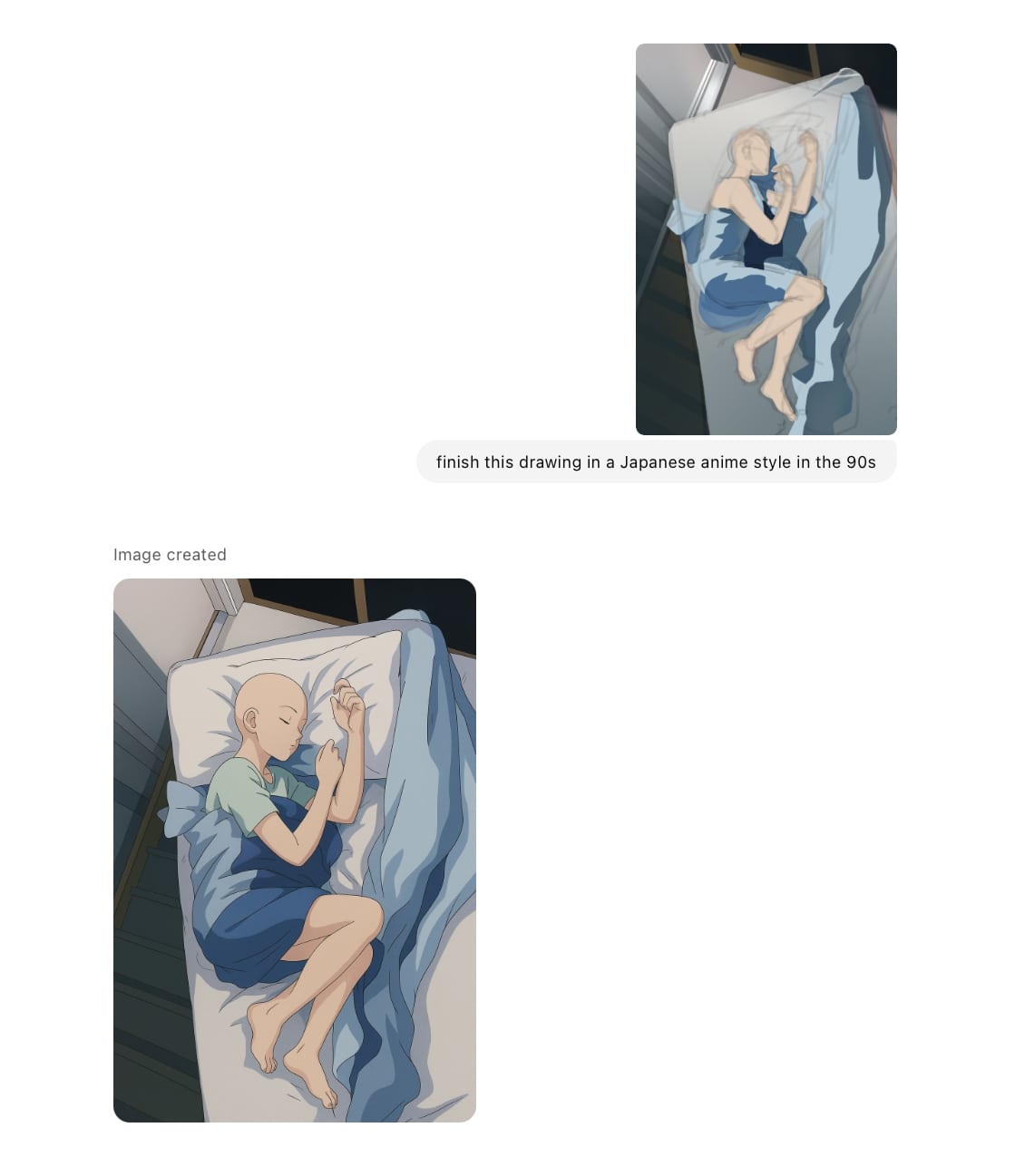

ChatGPT completed a drawing within minutes based on a sketch made by my freelance artist friend, Robin Lee, following a specific artistic style command without crediting the original source.

Generative artificial intelligence (or GenAI) is defined as an intricate type of AI which is capable of creating a variety of new media content such as texts, photos, videos, etc. by using machine learning algorithms (Garcia 2). This definition suggests the profound evolution of GenAI in the past few years, where at first it only interacted and analyzed data, but now is capable of synthesizing and generating new content. In the field of arts, a random search for GenAI art tools on Google will return many of these models, ranging from basic to advanced programs, including DALL-E, OpenArt, PixAI, etc. GenAI art tools, being developed exponentially in terms of their quantity and quality, are predicted to eventually be more adopted by artists and the general public.

This potential widespread adoption of GenAI in creative fields has reached its most controversial point, highlighted by a strike of Hollywood filmmakers in 2023 to oppose GenAI’s film products such as written scripts and deep fake actors. Filmmakers argued that GenAI models should be used as assistance tools while creative workers should still be fairly compensated and given opportunities to not be replaced by GenAI. Although this event made a significant echo all over social media at that time, it was still not enough to impede the development and employment of GenAI in recent years, specifically in the field of filmmaking.

Another example is when, at the beginning of 2025, an AI art auction held in New York city by a British auction house named Christie’s has become a controversial topic. While AI arts displayed in this auction were created by so-called “AI-pioneered” artists like Refik Anadol, they received bitter disapproval from many artists around the world for not crediting copyrighted artworks. In a post by CNET, a part of the opposing letter signed by thousands of worldwide artists stated “These models, and the companies behind them, exploit human artists, using their work without permission or payment to build commercial AI products that compete with them.” (Cooper). This highlights the two opposing views of human artists towards GenAI arts in which some artists fully embrace the use of GenAI while others intensely oppose the use of these tools which are said to “compete with them.” This leads me to question whether my friends and other human artists will ever be overtaken by GenAI while having their works to be unfairly used, and the most reasonable answer I have found to this question is “AI will not replace artists in the future” and GenAI “will still require the guiding hand of a human artist” (“Why the growth”).

The first reason for me to believe human artists cannot be fully replaced by GenAI tools is that GenAI arts lack human perspectives. The scandal of Christie’s AI art auction revealed that AI-generated arts are just a combination of preexisting copyrighted artworks. People with a heart for arts do not love artwork solely because they look aesthetically pleasing, but they rather want to see pieces of art which contain unique human perspectives. Human elements that human artists bring into their arts can be varied, but they are mostly intangible elements like personal lived experiences, emotions, innovative ideas, and even imperfections. Garcia highlights that although AI-generated artworks are technically remarkable, they lack the personal touch, intent, and contextual depth that give human-created art its authenticity, with elements like unique experiences, emotions, viewpoints, and deliberate decision-making of the artists behind their artworks being vital to the traditional artistic creation and challenging to the current GenAI technology’s replications (4).

To support this statement, Garcia specifically gives an example of styles of Renaissance painters which played a significant role in art history. The Renaissance was a period of transformative historical movements that brought a renewed understanding of humanity, the natural world, and human relationships under many influential styles of painters such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and El Greco (Renaissance art). This point of view of Garcia aligns with Lee’s opinion: “An AI can not explain its decisions to create something in the way it did” while “a person that creates something always has thoughts behind it” and “someone who draws all their faces a little crooked does that for a reason, maybe the artist is still learning, or it is his personal liking” (personal communication). Therefore, GenAI might be considered as a powerful tool to assist artists, but I strong believe that GenAI-created artwork would not overtake human-created art in delivering the contextual depth, symbolic meanings, and intentionality that are filled with the artist’s experiences shaped by various cultural, societal, and historical factors in their time. Being aware of this limitation of GenAI-made arts, human artists, specifically, so-called “pioneered artists in AI” should reconsider their reliance on GenAI to ensure that human artistry remains valued.

In another attempt, when given the same command, ChatGPT refused to create a drawing out of Lee’s sketch, citing content policy violations.

The importance of human perspectives in the creative process begs the question about the value of authenticity and originality of human-made art. Originality and authenticity can be defined differently under cultural, aesthetic, and legal contexts, with an “original” artwork being legally defined as a work independently created by a particular artist that possesses a minimal level of creativity while authenticity of an artwork refers to the audiences’ perceived historical and cultural values shaped by the artist’s personal perspectives at the time the work is originally created (Gerstenblith 324, 325, 327). Based on these definitions, GenAI artwork cannot be considered as legally original and cannot bring the same value of authenticity to the audiences. The distinction in how GenAI-made arts and human-made arts are valued by audiences and regulated by the laws depicts the important role of human artists in the creation of original and authentic works.The legal definition of an “original” artwork also emphasizes the importance of human artists’ creativity.

In contrast to human creativity, Garcia defines “artificial creativity” as a formation from the analyses of large datasets and complex machine learning algorithms to produce works that mimic the nuances of human creativity, and this type of creativity lacks authenticity and intentionality of the artist for its work to be considered as creative (3). This definition of “artificial creativity” suggests that arts made by “artificial creativity” are just products of replicated human creativity and without the continual fuel of consciously human creativity, GenAI tools will stagnate and die off. Lee agrees on this as she said, “I don’t think artistic creativity can be recreated by machines or AI” and “[artists] can put brushstrokes on a canvas that seem strange to others”, but if they are asked, “they might explain what it meant, what their thoughts were when they drew it that way” (personal communication).

Originality and authenticity of human-made arts are core values in the perception of art audiences. Messer states that the level of creative authenticity assigned to an artifact depends on the perceived involvement of the creator, and artwork in which the artist has greater creative control is considered more authentic and receives higher recognition (2). Messer’s experimental artwork supports this statement as it showed that arts co-created between humans and GenAI were perceived as less artistical, less authentic, and lacking effort compared with the identical human-made arts, leading to GenAI co-created arts receiving lower recognition from the survey participants (Messer 10).

The legal copyrights of human artworks is another important aspect when it comes to the competition between human artists and GenAI models. Although GenAI can independently produce artworks, existing copyright laws do not grant protection to these pieces of works (Garcia 5). This means human artists are granted exclusive rights over their works under current copyright laws, protecting their intellectual properties from unauthorized use or modification. To suffice for this legal rights of human artists, Lee said, “An image created with the use of AI cannot claim ownership of it, even if the creators of the AI claim so” (personal communication). Lee questions whether so-called “artists that pioneer in AI” should really claim their GenAI-made works under their ownership, without proper attributions or compensation to the artists of copyrighted works.

In this photo, Robin Lee is seen finishing a drawing for the sketch that we used to test ChatGPT’s art generative capabilities.

This speaks to the issue of disclosure of GenAI use in the artistic process. Artists widely agree that transparency and disclosure of particular images used to train an AI model are crucial for them to consider that model to be fair and acceptable and 80.17% of artists believe that AI model creators should provide detailed disclosure about the content used in the training of their models (Lovato et al. 910). Lee also has the same idea about this matter of GenAI legal regulations as she said, “Changes like every art will be checked to make sure it will not be AI” (personal communication). Despite the quest of human artists to have the details of their works disclosed by GenAI tools creators, this type of legal transparency protection is still in its early form of development. For example, the EU AI Act is one of the first established legal obligations where developers are asked to be more transparent about the contents they use for the training of their GenAI models (Valentine and Haidar). With this lack in the legal frameworks of GenAI use, I strongly agree with Lee and other artists that more detailed regulations and laws such as the EU AI Act, should soon be made to reinforce the roles of human artists and re-emphasize the legal values of their works.

Although this project aims to re-establish the irreplaceable role of human artists in the creative artistry process, there are possible venues for collaborations between human artists and GenAI tools. Garcian introduces the concept of “human in the loop,” which states that AI is capable of interacting with human users, learning new information, and adjusting its functions accordingly (7). This new way of co-creating artworks is said to be transforming the traditional creative process of artistry. For example, artists traditionally spend significant time sketching intricate scenes or characters, but there will be a change in this process in which artists give input of rough concepts and ideas for the AI to produce detailed output (Garcian 7). I believe this approach would allow artists to have more time and mental resources to add nuance to their existing work while also boosting their productivity in producing more valuable work. However, Garcian noted that in this human and GenAI co-creative process, artists must carefully manage their input to ensure the final artwork reflects their vision while also leveraging the innovative potential of GenAI (7-8).

There is also a hope for an emerging market for GenAI-made arts and co-created human-GenAI arts with the fully-integrated digital buying and selling transactions. OpenSea is a marketplace platform where artists are able to earn royalties by setting a percentage of sales as ongoing earnings from future transactions whenever their AI-made artwork is resold on the digital secondary marketplaces (Garcian 9). However, for this type of art market to sustainably exist, I think there should be a greater appreciation amongst the public towards the mentioned human perspectives embedded intangibly in these arts. The virtual availability of GenAI-made arts will also grant artists endless capability to provide art therapy and art education to individuals across the world. Garcia details “AI art therapy” as a practice that entails working with AI to create arts that provide individuals with customized and adaptive therapeutic and psychological healing while GenAI can act as an interactive assistant in virtual art classrooms to help students explore various art styles or techniques (11). These scenarios predict a future where young generations are those first to embrace these new types of GenAI tools, as Lee explains: “A new generation that grows up with AI art today may see it as normal as everything else” (personal communication).

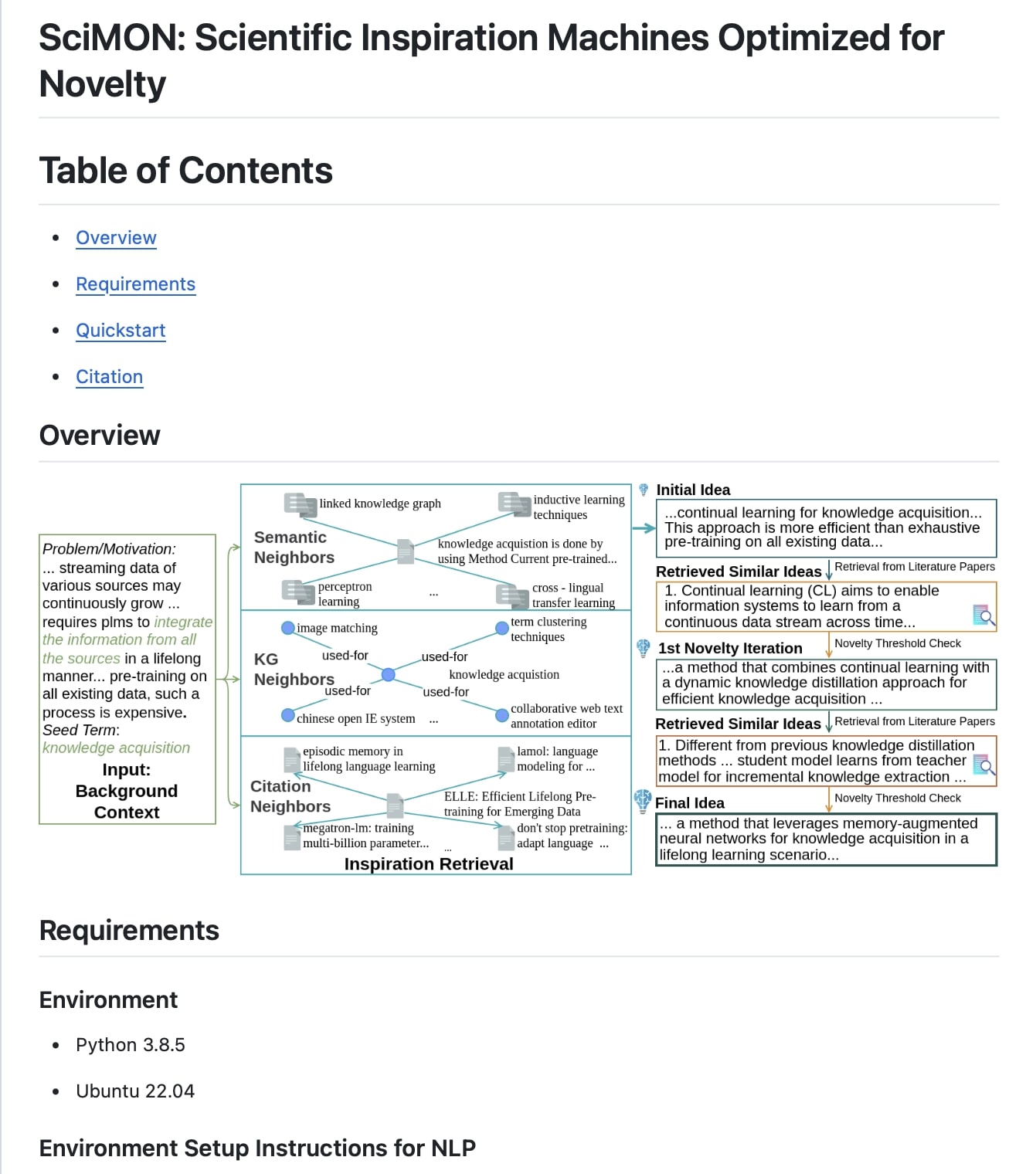

SciMON, a powerful large language model specializing in scientific literature and novel idea analysis, requires substantial knowledge of programming languages such as Python and operating systems like Ubuntu, making it less accessible to the general public and those without a background in computer science.

Although AI is said to be mainly designed and developed by computer and data scientists, as a science student majoring in biomedical research, I think scientists in other fields will find themselves facing the same reality of GenAI as the artists. Human artists’ roles are specifically challenged by GenAI – a subtype of AI technology while roles of scientists will be challenged by a larger concept of AI constituted by powerful large language models (LLMs) and neural networks. Similar to GenAI’s capability to handle basic artistry tasks like sketching or generating concepts of drawings, current LLMs or neural networks can now manage basic science tasks. Advanced and pre-trained LLMs are now capable of analyzing pre-existing scientific research, deriving scientific theorems, handling data-driven tasks, and even executing designed experiments with a low level of human control (Reddy and Shojaee 2). Eventually, I believe that AI tools might be used in place of human scientists to save time and minimize the loss of profit in contexts where time and resources are limited.

Therefore, many more scientific AI models are seen being specialized with this purpose in mind. Examples are SciBERT and SciMON which are pre-trained LLMs in analyzing scientific literature and creating novel scientific ideas and AI Feynman – a neural network model, capable of reconstructing physics laws from given data and integrating constructed physical principles and structures to build better scientifically grounded models (Reddy and Shojaee 2). This again suggests a higher possibility that human scientists are going to be needed less and less in various steps of the used-to-be human-driven scientific research process. However, other evidence gives hope to the human scientists that they will not be replaced by these powerful AI tools. Humans face limited cognitive capability to process information in a superfast manner compared to GenAI models like ChatGPT4, but humans possess curiosity and imagination about unknown experimental events, making it easier for humans to make divergent thinking to create different fundamental hypotheses from scratch (Ding and Li 9). This finding aligns with the first claim made in this research, stating that GenAI lacks human perspectives to replace human artists in their artistry process. It also generalizes an important idea that human workforce will be an irreplaceable factor in the creative process as we drive and shape this algorithmic technology with our diverse intangible human perspectives.

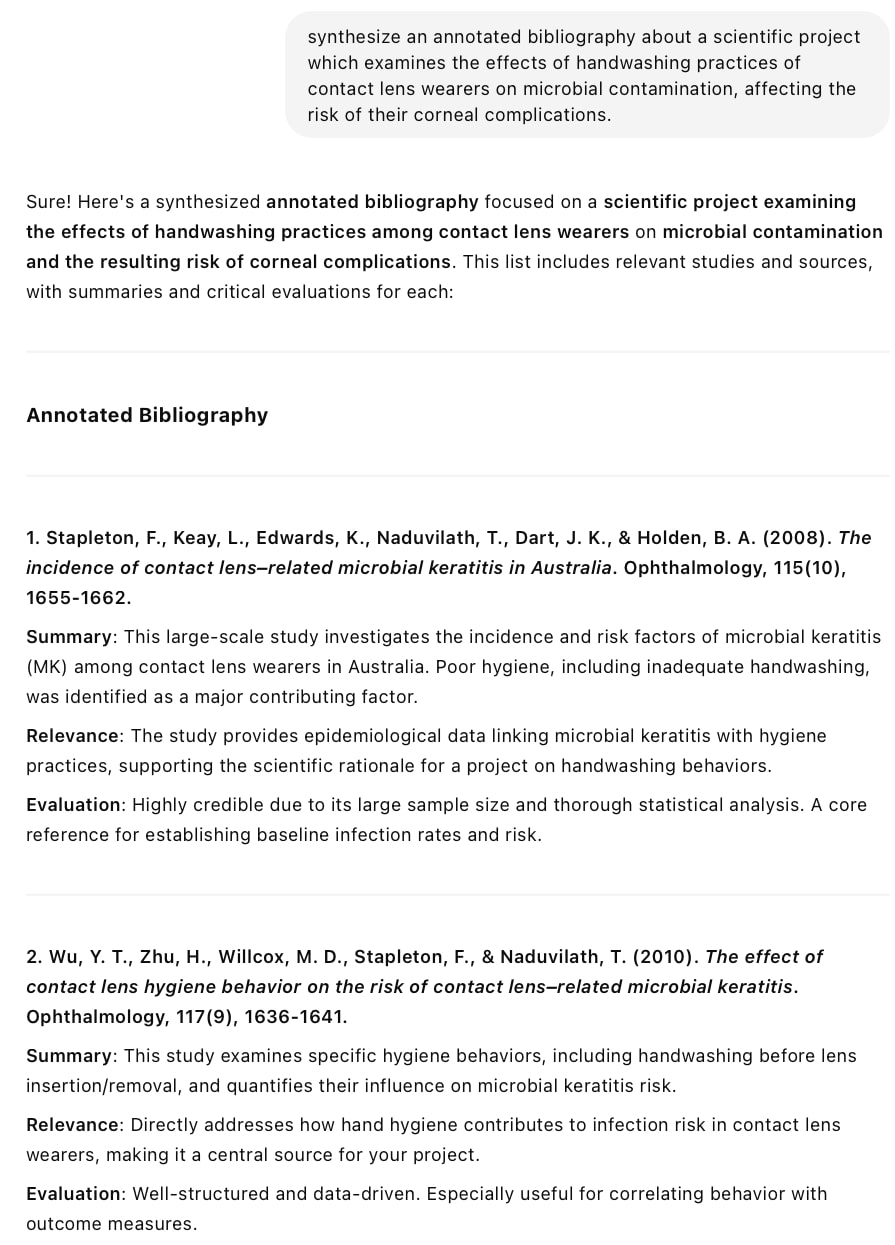

ChatGPT was tested to see if it could provide a meaningful annotated bibliography for my biomedical research project. However, the AI returned qualitative studies, whereas the more appropriate focus—emphasized by my SCI400 professor, Dr. Vaughan—should be on scientific and quantitative research.

GenAI will be an advanced technological development that possesses endless innovative capabilities to generate aesthetically pleasing artworks, but it will not ever replace human artists in their artistry creations. This machine-driven technology lacks human perspectives to create artwork that are perceived and certified as original and authentic under copyright laws and the eyes of audiences. For those artists who choose to embrace the use of GenAI art tools, they should be transparent to the public about their use of GenAI and should not over employ this technology. Business owners and leaders should be aware that human artists are an irreplaceable element to run the “human in the loop” of the creative artistry process and should give more recognition to them for authentic and original works that are shaped by their unique human perspectives. Although computer and data scientists are main drivers of AI technology, scientists in other fields of science need to be aware that AI (or Gen AI) technology is growing fast to potentially play their roles in basic scientific discovery steps; and just like in the artistry creations, human perspectives will be the core element that keep us as human researchers being an irreplaceable factor in this journey of scientific study. Lastly, GenAI models should only be acknowledged as useful tools to complement the works of humans and assist us in boosting the productivity of the creation of our work.

References

Cooper, Gael. “Christie’s First-Ever AI Art Auction Earns $728,000, Plus Controversy” CNET, 6 Mar. 2025, https://www.cnet.com/tech/services-and-software/christies-first-ever-ai-art-auction-earns-728000-plus-controversy/

CVL Economics. Future Unscripted: The Impact of Generative Artificial Intelligence on Entertainment Industry Jobs. 2024. https://animationguild.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Future-Unscripted-The-Impact-of-Generative-Artificial-Intelligence-on-Entertainment-Industry-Jobs-pages-1.pdf, PDF file.

Ding, Amy Wenxuan, and Shibo Li. “Generative AI lacks the human creativity to achieve scientific discovery from scratch” Scientific Reports, 15, 2025. Research Gates, doi:10.1038/s41598-025-93794-9

Garcia, Manuel B. “The paradox of artificial creativity: Challenges and opportunities of generative AI artistry” Creativity Research Journal, 2024, pp. 1-14. Taylor & Francis Online: Peer-reviewed Journals, doi: 10.1080/10400419.2024.2354622

Gerstenblith, Patty. “Getting Real: Cultural, Aesthetic and Legal Perspectives on the Meaning of Authenticity of Art Works” Columbia Journal of Law & the Arts, vol. 35, no. 3, 2012, pp. 321-356. Elsevier, https://doi.org/10.7916/jla.v35i3.2169

Grand View Research. AI Image Generator Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Component (Software, Services), By End-user (Media & Entertainment, Healthcare), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2024 – 2030. 2023. Report no. GVR-4-68040-100-5. www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/artificial-intelligence-ai-image-generator-market-report, PDF file.

KOAA. “KOAA Survey: Should AI-generated images be considered art?” KOAA News5, 01 Sept. 2022, https://www.koaa.com/news/news5-originals/koaa-survey-should-ai-generated-images-be-considered-art

Lee, Robin. Interview. Conducted by Ngoc Ngan Lam, 17 Mar. 2025.

Lovato, Juniper, et al. “Foregrounding Artist Opinions: A Survey Study on Transparency, Ownership, and Fairness in AI Generative Art”. Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, vol. 7, 2024, pp. 905–916. AAAI Publications, https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AIES/article/view/31691/33858

Messer, Uwe. “Co-creating art with generative artificial intelligence: Implications for artworks and artists”. Computers in human behavior: artificial humans, vol. 2, issue. 1, 2024. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbah.2024.100056

Reddy, Chandan K, and Parshin Shojaee. “Towards scientific discovery with generative AI: Progress, opportunities, and challenges” Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, 2412.11427v2, 2024. arXiv, https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.11427

Renaissance art: History, impact & influential artists. Lindenwood University Online, 16 Oct. 2024, https://online.lindenwood.edu/blog/the-renaissance-art-period-history-effects-and-influential-artists/ Accessed 28 Mar. 2025.

Valentine, Frank, and Leo Haidar. “As transparency obligations on AI providers increase in the EU, will infringement claims and even a Collecting Society approach follow?” DLA Piper, 10. Jan. 2025, https://www.dlapiper.com/en/insights/publications/2025/01/as-transparency-obligations-on-ai-providers-increase-in-the-eu

“Why the growth of AI in making art won’t eliminate artists.” The Conversation, 8 Aug. 2023, https://theconversation.com/why-the-growth-of-ai-in-making-art-wont-eliminate-artists-210187