Kailee Hanke

Kailee Hanke (she/her) is completing her Bachelor of Arts degree in Psychology at Capilano University. Kailee previously attended Hofstra University for Pre-med, music production, and music performance, where she had the dean’s list scholarship and the Marine Corps “Semper Fidelis” music award scholarship. At Capilano University, she has been named to the dean’s list twice while also working. In the future, Kailee plans to continue her education to become a counselor to work with marginalized communities.

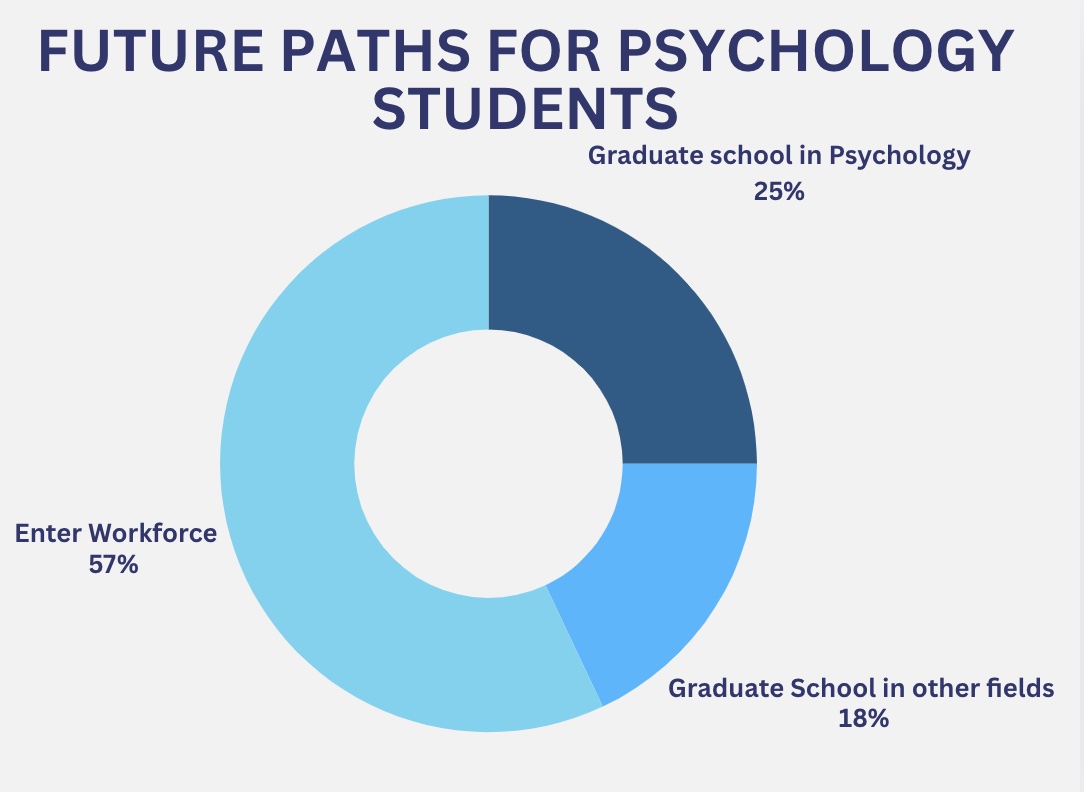

“Looking back on it, I hated those fucking classes… like oh my God, shoot me in the head. I never want to take that class again. It just wasn’t what I was hoping psychology would be” (Riley Bizzotto, personal communication, February 28, 2025). Riley Bizzotto, a future PhD student at the University of British Columbia (UBC), completed her undergraduate degree in Psychology at UBC, intending to become a counselor or forensic psychologist. However, upon finishing her undergrad, she decided to leave the discipline, citing disillusionment with her coursework and negative experiences with several professors. Her story, unfortunately, is not unique. According to the American Psychological Association, “Twenty-five percent of psychology baccalaureates go to graduate school in psychology, about eighteen percent go on for more education but not in psychology, and fifty-seven percent are workforce graduates” (Landrum, 2018). This statistic implicitly reveals that seventy-five percent of psychology undergraduates do not continue in the field. Why is that? While not every psychology student intends to pursue a career in psychology, in which further education is required, it is worth asking whether certain aspects of the educational experience actively discourage students from doing so. Psychology is a discipline that, in theory, examines the whole person, from observable behaviors to underlying biological mechanisms. Yet, in academic settings, the field can feel sterile, unbalanced, and marginalizing. There is a disproportionate emphasis on quantitative data, often at the expense of narrative, lived experience, and human emotion. Theory and hard science are prioritized, while the practical application is frequently neglected. Course content tends to be repetitive, and the experiences and contributions of marginalized communities are often overlooked or reduced to mere footnotes in lectures and textbooks. These shortcomings can lead to feelings of alienation among students who may be members of such communities, who also often have ostracizing experiences in school. Psychology, at its core, is meant to be a discipline about people– all people, all of the person. When students are not given a balanced, safe, inclusive, and engaging education, dissatisfaction can grow, leading some to leave the field or school altogether.

“Twenty-five percent of psychology baccalaureates go to graduate school in psychology, about eighteen percent go on for more education but not in psychology, and fifty-seven percent are workforce graduates” (Landrum, 2018). Could there be underlying issues causing seventy-five percent of psychology undergraduates not to continue in the field?

The field of psychology in its setting of academia has lost its focus and balance, ironically dehumanizing a discipline about people. As it currently stands in 2025, curriculums are changing, and there is a shift toward favoring hard data over the humanist approach–hard data being statistics and biological elements of the discipline. This shift means the field is losing students, and it has farther reaching effects than student happiness and retention rates in undergrad programs. Without addressing classes and textbooks, repetitive content that focuses primarily on hard data and leaves marginalized communities as footnotes, things will stay the same, and more students will have the same experiences. Students in psychology were asked how they were educated, and they mostly responded with how and where it failed them.

Reflecting on both my own experience as a psychology undergraduate and those of my peers, there were common themes that emerged regarding expectations of the discipline versus what was actually experienced. Students had much to say about their time in the classroom and their experience with professors, and while some of it was positive, most of it was critical of what they had experienced. Another common theme was looking at the diversity of content being taught, if it was repetitive, and if the material was diverse in who and what it covers. Finally, I examine how well balanced the discipline felt, looking at theory and application, and hard science versus personal connection and the human element.

When the experience in the classroom and with your professor has left a lot to be desired, students leave discouraged, sometimes questioning if they’re in the right discipline. Riley Bizzotto experienced this at UBC in her undergrad, where she proposed a research project involving urban Indigenous communities to her advising professor and was squarely rejected.

I remember sitting in there and explaining why I thought the research was really important. I thought it would have a really positive impact on the people we’re working with, and he was like, there’s not enough Indigenous people in Vancouver for this to matter…these aren’t questions that are ever going to be funded, aren’t questions that are ever going to be good enough for grad school. You need to be more specific and discerning in the questions you ask, and understand what actually is important. And I remember sitting on the couch and he’s in his office chair and he’s just leaning back with his feet up on the coffee table while he’s saying this …And I’m just trying to convince myself not to cry, and then when I finally got out of there I sat and cried for two hours, I was mad about what he said, that it didn’t matter. There weren’t enough of us to matter. That who cares about these kinds of questions? But I was also really frustrated that he was saying I was never gonna get into grad school because that’s all I’d ever wanted since I started university and it was just blow after blow, just so much and I just was bawling my eyes out (Riley Bizzotto, personal communication, February 28, 2025).

After this Riley decided to do her masters in a different discipline, she didn’t care what as long as it didn’t disregard what she wanted to study, the way her psychology advisor had. Her experience with that professor was the breaking point that led to her changing disciplines, showing how much interactions with professors can shape a student’s journey.

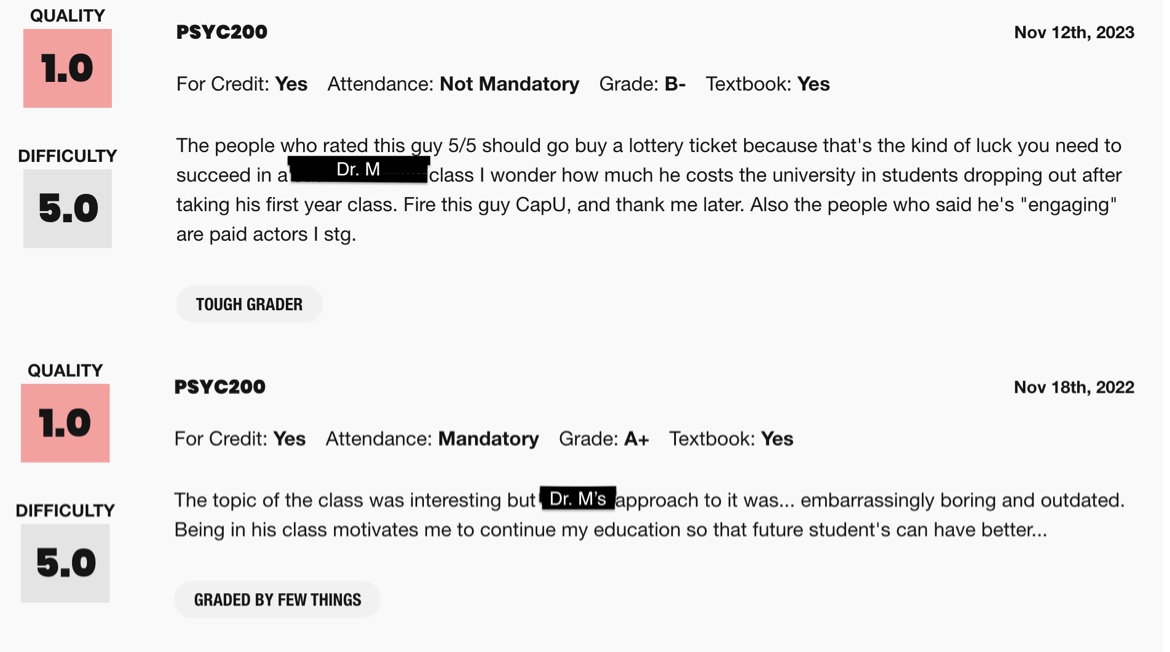

At Capilano University, students had similar poor experiences in the classroom and with professors. Sarah Humchitt, an Indigenous student who is minoring in psychology and is almost finished with her undergrad degree, reflected on her educational journey, making note about one specific professor who will be referred to as Dr. M.

In my first few years studying psychology at Capilano University, I had some really bad experiences with instructors, though at the time, I didn’t fully recognize how problematic they were. One instructor in particular, [Dr. M], stood out. In an assignment that asked us to reflect on our own psychology, I explored how the atrocities committed against Indigenous peoples in Canada had shaped me. I felt I had provided a strong, well-structured outline, but the feedback I received dismissed my perspective. [Dr. M] wrote that I hadn’t provided “enough detail” about myself, as if the impact of intergenerational trauma needed to be laid out in deeply personal, almost clinical terms for it to be valid. It felt less like an academic critique and more like a demand for personal material to be studied—yet another example of Indigenous trauma being dissected in an impersonal way, rather than understood with care and respect. This experience reinforced what I had already started to notice about psychology as a discipline: it often focuses on Indigenous peoples through a lens of trauma, without considering the full person, their strength, or the broader cultural context. Instead of engaging with my perspective on how systemic harm had shaped me, the instructor seemed to want raw details to fit into a predefined narrative of Indigenous suffering (Sarah Humchitt, personal communication, March 28, 2025).

Sarah’s experience with her education and with that one particular professor is not uncommon. Students who are a part of marginalized communities like Indigenous People face ostracizing events frequently in education and psychology in academia. “Although rates of school psychology graduate students from minoritized backgrounds are growing, they experience barriers that reduce perceptions of belongingness, reduce academic engagement, and prevent success in graduate study” (National Association of School Psychologists, 2021).

Student reviews from the website Rate My Professor for Dr. M. Many students go there to give their honest feedback about a professor.

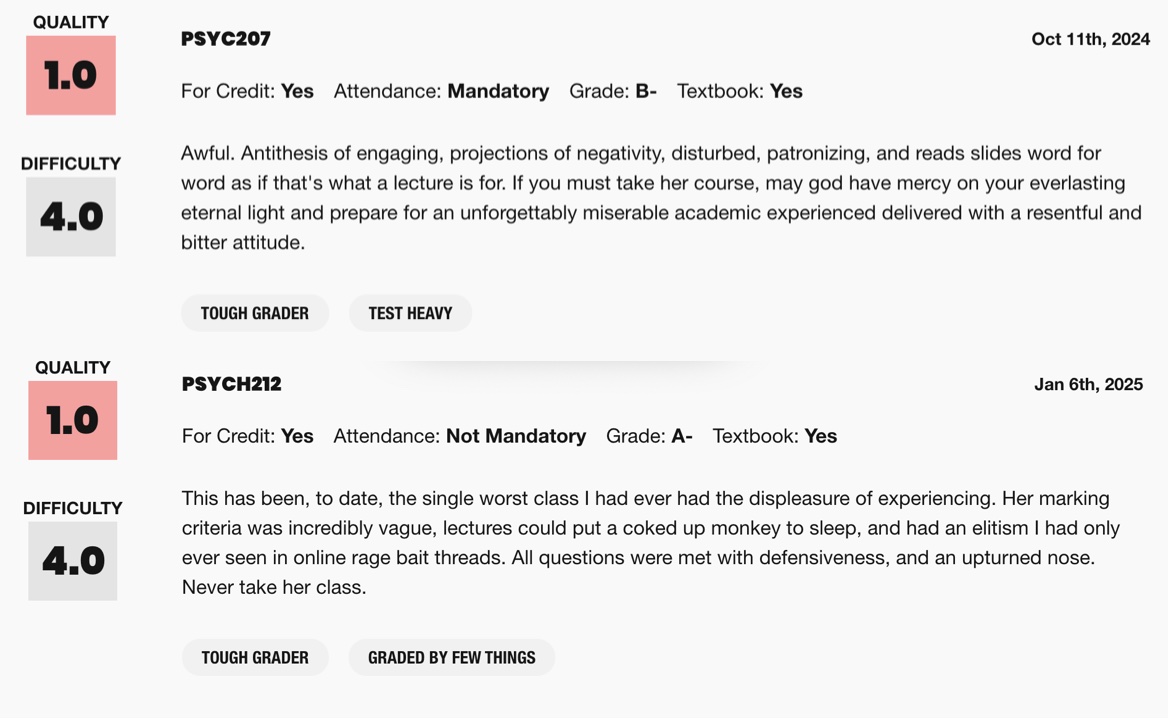

I too have had poor experiences in classrooms and with professors, such as one professor who will be referred to as Dr. G, whose name can be said among psychology students at Capilano and unanimously they will respond negatively. In the classes I have had with her, she has belittled and demeaned students, both in class and over emails. The class is often on edge, feeling unsafe, as her sometimes explosive attitude makes its appearance at least once a semester, leaving students reluctant to attend class or participate. She gives vague and disorganized instructions for assignments and then grades harshly, with little explanation as to what was missed. The environment she creates is unwelcoming, as she has stated in her syllabus’ that she does not wish to be contacted for trivial things like being sick or having extenuating circumstances that cause you to miss anything. It is professors and experiences like these that cause students to question if they should continue school at all.

Avery Wood, a psychology undergrad who is almost done with her degree took a break from school for a while citing Dr. G as one of the underlying factors.

You can’t tell me that it’s just the person’s fault, because I have experienced taking her class when I was not at my best, and I have experience taking her class where I was a lot more stable, a lot more happy, healthy and everything in between. But somehow, still it comes short. And you can look at a piece of paper and have it written out for you. But if it doesn’t work for you, it’s not going to work for you. Trying to force yourself to fit someone else’s rubric is patronizing, demeaning, doesn’t make you feel like a person, doesn’t feel like you’re regarded. It does not in any way promote you or give you drive or anything like the sort to continue (Avery Wood, personal communication, March 25, 2025).

Both of our experiences with Dr. G are unfortunately shared by many of our peers, and those kinds of interactions lead to growing disinterest and a loss of passion for the subject. When you’re treated poorly by those you are learning from, you start to lose any interest in continuing along that path.

However, there were some good classroom experiences and interactions. Between myself and my peers, there were several professors with whom we had good interactions, one universally being Dr. Justin Wilson, an Indigenous psychology professor at Capilano. Sarah Humchitt spoke highly of Dr. Justin Wilson, sharing that:

As I entered the final years of my bachelor’s degree, I found that some instructors were immensely better than the ones I had taken previously. They didn’t just teach psychology—they respected their students as individuals, including me as an Indigenous person, rather than treating my identity as a case study. One instructor who stood out was Justin Wilson. I had initially taken his class reluctantly, skeptical of what I could learn from an “urban Native” from my own community. How could he teach me more about Indigenous psychology than I already knew? But as the course progressed, I realized how wrong I had been. His unique blend of personal experience and educational background didn’t just complement my own—it reshaped how I viewed psychology altogether. Through his teaching, I began to see the field in a new way, one that wasn’t just about diagnosing problems but about understanding people within the full context of their lives (Sarah Humchitt, personal communication, March 28, 2025).

This shows that respecting students and their identities alongside their job of teaching psychology makes students feel much more welcome and allows them to engage more with the content, Sarah felt that Dr. Lesley Schimanski and Dr. Mark McPhedran also achieved this as well, and I felt that Dr. Jennifer Davis did the same.

I found Dr. Justin Wilson’s classes and teaching style to be different from most other psychology classes in a more engaging way. We would often sit facing each other so that whoever was talking could be seen and acknowledged, which led to deeper discussions than we would have in classes where we all face the projector screen with lecture slides pulled up. Our thoughts and opinions on the material mattered, and we were allowed to use both I statements and more approachable language in assignments without being marked down, as psychology in academia is known for discouraging both. Dr. Justin Wilson feels that psychology in academia is generally focused on studying, with no focus on relationality or interconnection, which is a need in a field like psychology, especially for future counselors (Personal Communication, April 4, 2025). He also feels that psychology doesn’t need to be binary, and get stuck in the science and lose its humility (Personal Communication, April 4, 2025). In his classes, he recognizes these things and actively works to make psychology more human and inviting to all students.

Student reviews from the website Rate My Professor for Dr. G. Clearly, the professor has evoked some impassioned responses from students.

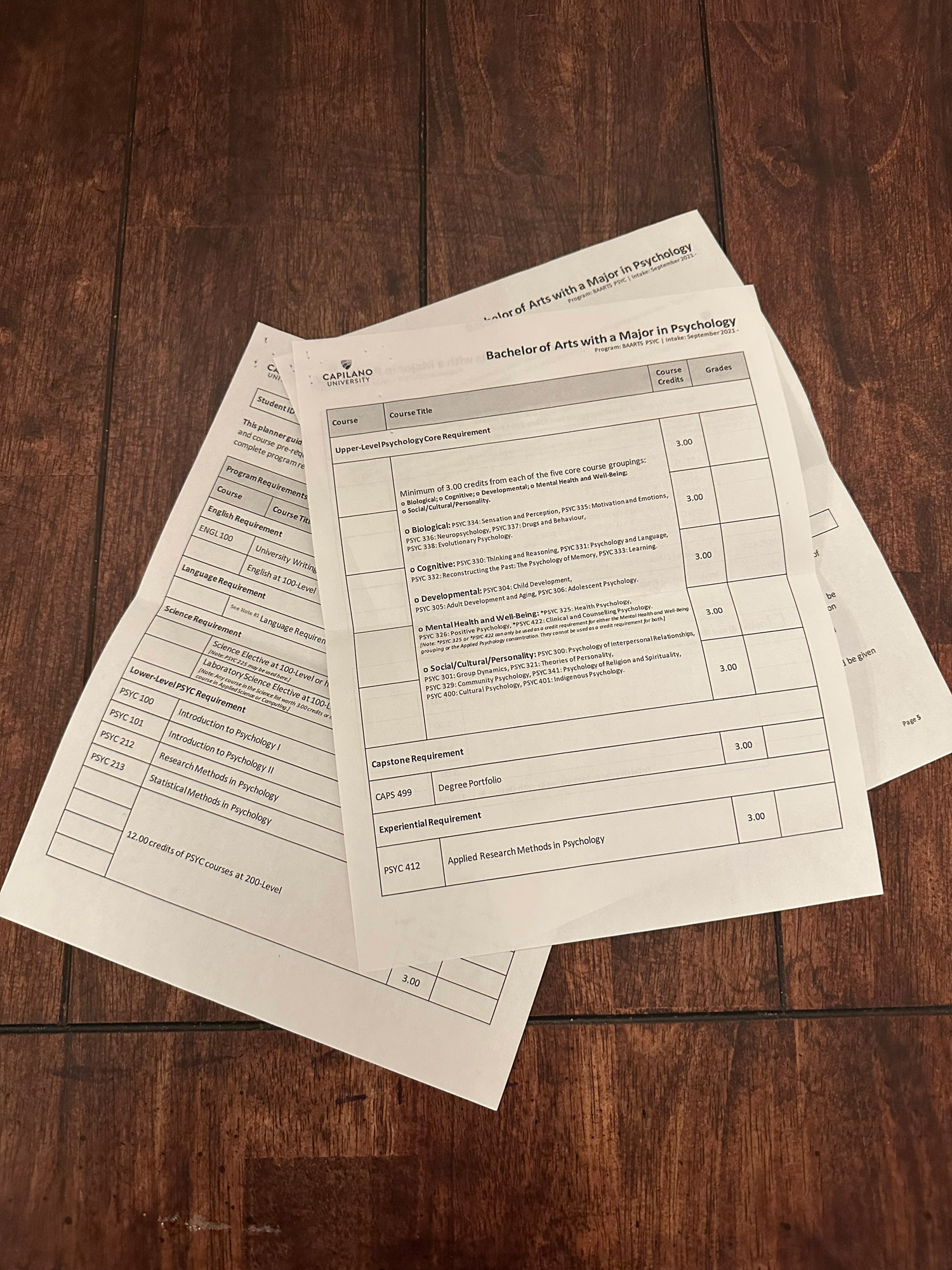

Looking at the diversity of content taught in psychology, there is often much left to be wanting. The content seemed to be repetitive, the same thing time and time again, from constantly covering Freud to learning about the same biological processes in several different classes with no new information being provided. This constant overlap and repetitiveness is one of the factors leading to disinterest in students, in both attending class and staying in the discipline. The reason for this at Capilano University could be the recent growth from an AA to a BA in psychology, but Riley Bizzotto shared the same sentiments about repetitiveness from her time at UBC. Another aspect is the lack of diversity present in who and what is covered. Marginalized communities such as Indigenous People or the LGBTQIA+ are footnotes at best in most textbooks and rarely discussed in class if at all. Riley Bizzotto wisely pointed out that, “There are going to be differences between Indigenous People and white people and we can’t approach psychology as this blanket discipline that explains every person’s behavior if we’re not doing the work to understand how different groups work” (Personal communication, February 28, 2025).

The gap present in the literature about marginalized communities presents problems for the discipline, showing that it is a gap in knowledge that isn’t being bridged. While the field of psychology is slow to bridge this gap, as it wasn’t until February 2023 that the APA published its apology for “ its contributions to the harms that First Peoples and their communities have suffered”( APA), there should be some kind of noticeable strides in academia, since we are constantly getting new editions of our textbooks, or at the very least professors should be doing the work to bridge the gap when teaching us. However, professors seem to be reluctant to cover material about marginalized communities unless they themselves have some kind of connection to them, which in my time at Capilano University, leads to two out of twelve different professors I’ve had covering content about marginalized communities. As someone who is a part of both marginalized communities previously mentioned, I have found it to be somewhat alienating. A large majority of my peers see themselves represented in the material we learn, but I get a sentence here and a paragraph there.

Capilano University’s degree requirements for a BA. The school’s growth from only offering an AA to a BA could have led to some of the repetitiveness in the material students learn.

Moving to how balanced psychology in academia is, it is noticeably unbalanced; psychology now favors hard science like statistics and biological processes over behavior and lived experiences. Dr. Nancy Eisenberg, who has over 40 years in the field of psychology, has noticed the field becoming more narrow, sharing her insights about the shift in an article.

As a consequence of the visibility and excitement about biologically oriented work, I have noticed a tendency toward reductionism by some individuals in the field and by some funding agencies. There seems to be an increasing tendency to assume that studying genetic/neural/physiological processes is more important than research on behavior and psychological processes per se because biological findings will eventually explain most of human psychological functioning. This belief is especially evidenced in the funding priorities at some of the National Institutes of Health. It can also be seen in the hiring patterns of many psychology departments that place a priority on hiring people who study biological processes or aspects of cognition that can be tied to neuroscience (Eisenberg, 2014).

This narrowing is seen in curriculums, textbooks, lectures, and throughout psychology in academia, and it has negative effects. Speaking with peers, they seem to enjoy and engage more with classes that offer a more balanced approach to the material, offering more than just statistics, and offering a narrative to the content. Lived experiences, showing that people are more than just a number on the page, engage students more, often reminding them why they were interested in the field in the first place.

Another imbalance in psychology in academia is seen in the prioritization of theories and the lack of explanations on the application of said theories. Avery Wood felt that, “We are taught to examine, less so to understand” (Personal communication, March 25, 2025), and I agree. We are not taught to apply the theories, to understand how they would really affect people. We are taught to examine the symptoms, but not the underlying causes. We are being taught half of what we need to or would expect to learn in a discipline like psychology. Riley Bizzotto felt that she was given, “Good methodological training and theory training, but …there wasn’t any training that made you a better listener or might help you understand people better… build better relationships” (Personal communication, February 28, 2025). This general sentiment was shared again by Sarah Humchitt, who felt that, “Another issue is that psychology tends to label individuals by their diagnoses rather than seeing them as whole people with unique experiences. This approach can be dehumanizing, reducing a person to a set of symptoms rather than considering their strengths, history, and community connections. For Indigenous people, the Western psychological framework can feel limiting and even harmful.” (Personal communication, March 28, 2025). Given what all of them say, it shows that this is a widely felt issue and is something that needs to be addressed moving forward.

There is a gap in the literature in psychology about marginalized communities that may not be seen by most, but is felt by those within the communities.

Evaluating all of these experiences in psychology in academia shows some of the glaring issues that the discipline is dealing with. Students are becoming disheartened by their educational experience and in some cases leaving the discipline altogether. I have considered leaving it myself many times, but have stayed because of those few good experiences with professors like Dr. Justin Wilson, who acknowledges all of these issues, sharing that he believes, “The wheels have to come flying off the car before anyone addresses it” (Personal communication, April 4, 2025). Dr. Justin Wilson also feels that psychology, as it currently stands, is falling short, with a negative focus, preferring to look at issues and not their causes (Personal communication, April 4, 2025).

However, if these issues are not addressed, there will be more problems than retention rates for the discipline. This unbalanced approach to teaching will affect those who continue in psychology and become counselors, for example. Avery Wood saw the effects of this when she met with a new counselor who was fresh out of school. Avery felt that the counselor would be able to recite textbooks back to her but was lacking in human connection (Personal communication, March 25, 2025). The quality, diversity, and balance of our education affect both the present and the future. It’s frustrating to hear your experience echoed by so many others, how students could wax on at length about what they’ve seen, gone through, heard, and then brush it off because that has seemingly become the norm. It seems universal to have abysmal experiences in class, with the content, or with a professor, and rarer to experience something so positive it sticks out from the poor and average and forgettable experiences. When I asked Riley Bizzotto if the psychology program had been different in her undergrad, more like what she had envisioned going into it, if she would have enjoyed her experience as a student more, she responded, “Yes, I think I would have enjoyed it more… I wouldn’t have dreaded going to psych class” (Personal communication, February 28, 2025). Dreading going to classes that are in your major shouldn’t be common, but it is an experience shared by myself and others. The field of psychology in its setting of academia has lost its focus and balance, and is ironically dehumanizing a discipline about people, and is failing its students.

References

“An Offer of Apology to First Peoples in the United States.” American Psychology Association, Feb. 2023, www.apa.org/pubs/reports/indigenous-apology.pdf.

Eisenberg, N. (2014, August 29). Is our focus becoming overly narrow?. Association for Psychological Science – APS. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/is-our-focus-becoming-overly-narrow

Landrum, R. E. (2018). What can you do with a bachelor’s degree in psychology? Like this title, the actual answer is complicated. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/ed/precollege/psn/2018/01/bachelors-degree

National Association of School Psychologists. (2021). Shortages in school psychology: Challenges to meeting the growing needs of U.S. students and schools [Research summary].