Michelle Mandelstam

Michelle Mandelstam earned a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology from Capilano University in the Spring of 2025. Her undergraduate studies fostered a strong interest in the application of psychological theory to the promotion of individual health and well-being.

Throughout her academic work, she engaged with topics bridging cognitive psychology and psychopathology within social context, paying special attention to the ways in which these fields can inform practice across diverse professional settings. She intends to integrate her insights into future professional endeavors.

Introduction

Pre-COVID, in 2019, Canada’s unemployment rate was at 5.7%, while today, it has sky-rocketed to 6.6% (Statistics Canada, 2025). Ironically, the 2019 job vacancy rate was much lower than it is today (Government of Canada, 2024). There has as such been an increase in available jobs and yet also an increase in job-hunting Canadians. How is it possible then, that despite many more Canadians looking for jobs, companies are in a greater search to find talent?

The present research aims to uncover Canadian Generation Z’s preferences on workplace conditions so as to provide employers with insight on the areas to which operational changes need to be made to attract and retain the generation now entering the workforce.

The Relationship Between Unemployment and Job Vacancy Rates

Canada’s current circumstances, in terms of the trends in unemployment and job vacancy rates both increasing throughout the past few years, are atypical. As defined by Statistics Canada (2017), the conditions for an individual to be considered unemployed involve them searching for, and immediately available for work, while the criteria for a job to be considered vacant involve the employer currently recruiting for a position that may begin within thirty days. There exists a statistically significant negative relationship between job vacancies and unemployment (Statistics Canada, 2017). That is, a high job vacancy rate is associated with a low unemployment rate, and contrarily, a high unemployment rate coincides with low job vacancies. Why is this relevant? Comparing job vacancy and unemployment rates provides insight into how effortful it may be for either individuals to find employment or for employers to find workers; as a note, (and a bit of foreshadowing), when the unemployment-to-job vacancy ratio is low, employers experience more difficulty in attracting and retaining employees (Government of Canada, 2024).

Canada’s Recent Trends in Unemployment and Job Vacancies

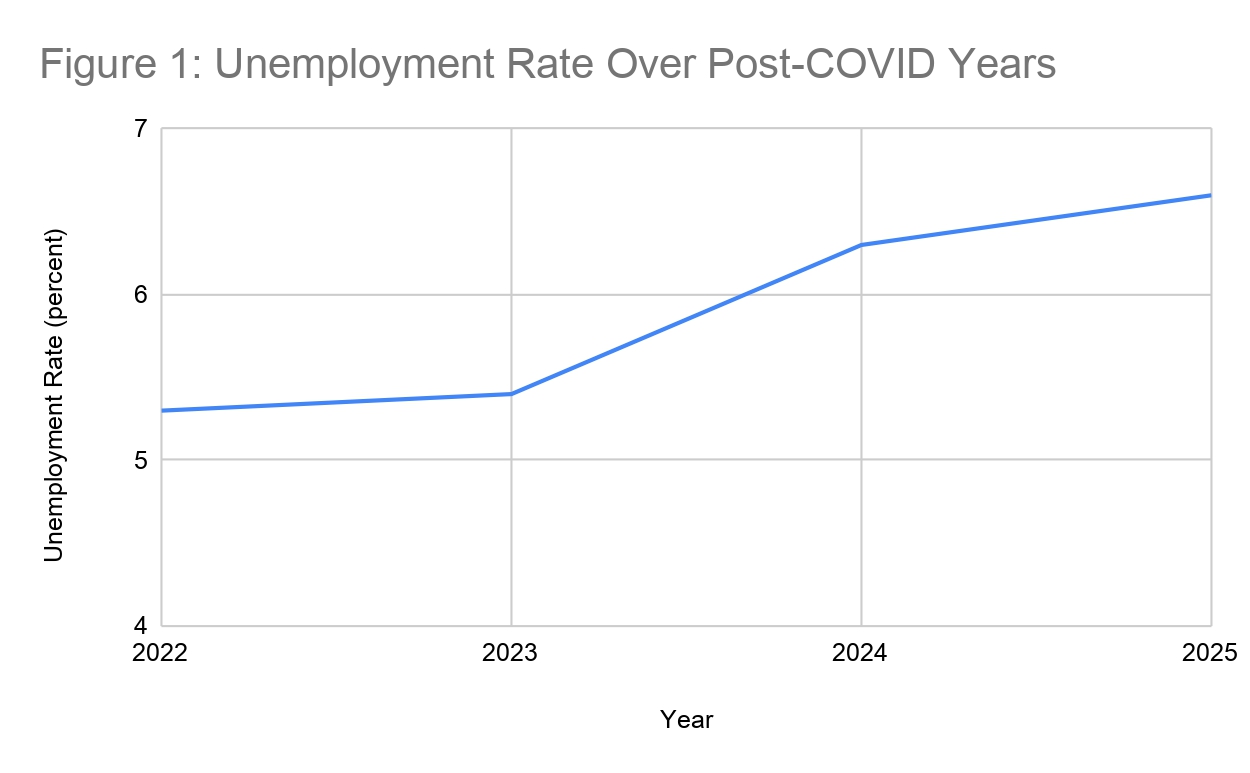

In 2016, for every job vacancy in Canada, there were 3.4 unemployed individuals (Statistics Canada, 2017). Since then, the number of job vacancies increased by two and a half times, bringing on labour shortages– which according to Statistics Canada (2023) refer to an “insufficient number of workers available to fill vacant positions.” Drawing from the most recent available data depicting Canada’s unemployment-to-job vacancy ratio, for every one job vacancy, there was an average of precisely two unemployed persons (Government of Canada, 2024). This means that, from an employer’s perspective, on average, since 2016, the proportion of available candidates for any given vacant professional position has reduced by over 40%! At the same time, in the past few post-COVID years, as depicted in Figure 1, unemployment has been on the rise (Statistics Canada, 2025). A rising unemployment rate is generally beneficial for employers, as deduced by the negative correlation between unemployment and job vacancy, but when the reducing unemployment-to-job vacancy ratio experienced since 2016 is taken into account, it becomes apparent that as much as unemployment is on the rise, it is no match for the magnitude at which job vacancies have increased. The negative relationship between unemployment and job vacancies prevails, however, not in favor of the employer.

Figure 1: Canadian unemployment rate over post-COVID years across all ages (Statistics Canada, 2025).

Causes for Recruitment Difficulties

A 2023 Statistics Canada report comparing unemployment and job vacancies by education found “no evidence that the recruitment difficulties experienced by Canadian employers seeking to fill positions requiring some postsecondary or higher education can be attributed to a lack of job seekers with such education levels.” It has in fact been found that since 2016, there have consistently been more unemployed Canadians holding a bachelor’s degree or higher education than there have been vacant positions necessitating such an education (Statistics Canada, 2023). Furthermore, job vacancies requiring a high school education or less have exceeded the number of unemployed persons with solely this level of education (Statistics Canada, 2023). As such, Canada’s high job vacancy rates are not a result of the population failing to meet employers’ educational requirements.

Alternatively, the report suggests that the root of these recruitment challenges is reflected by a mismatch between either the skills required for a position and those possessed by highly educated unemployed persons, or the wages offered by an employer and the unemployed individuals’ reservation wages, that is, the minimum wages at which individuals would be willing to accept specific work positions (Statistics Canada, 2023). Stemming from this, the report highlights several examples of factors that would lead to one of these two mismatches. In some instances, there may be a lack of accord between individuals’ fields of study and the fields of expertise necessary for vacant positions, in others, individuals may possess inadequate language skills, or work experience, and in others, the mismatch may be between “working conditions that prevail in some occupations and those desired by job seekers” (Statistics Canada, 2023). To help mitigate the recruitment challenges faced by Canadian employers today and in the coming years, the present paper aims to address the latter factor, in beginning to find the working conditions preferred by the generation steadily entering the workforce– Generation Z.

Why the focus on Generation Z?

A generation is not simply a range of years between which individuals are born– we are tied to each other by our generations in terms of our interpretations of our similar circumstances, whereby we attach shared meanings to them and see the world homogeneously (Grayson, 2021). With the baby boomer generation (born between 1946 and 1965) leaving the workforce, the three generations that remain include generation X (born between 1966 and 1980), generation Y (born between 1981 and 1996), and finally, those born between 1997 and 2012, generation Z (Statistics Canada, 2022). As discussed by Statistics Canada, 2022, “younger generations, such as millennials and Generation Z … now make up a considerable share of the working-age population, leading to changes in the labour market.” It is as such worthwhile to assess the recent shift in Canada’s unemployment-to-job vacancy ratio within the context of the influence of generational differences.

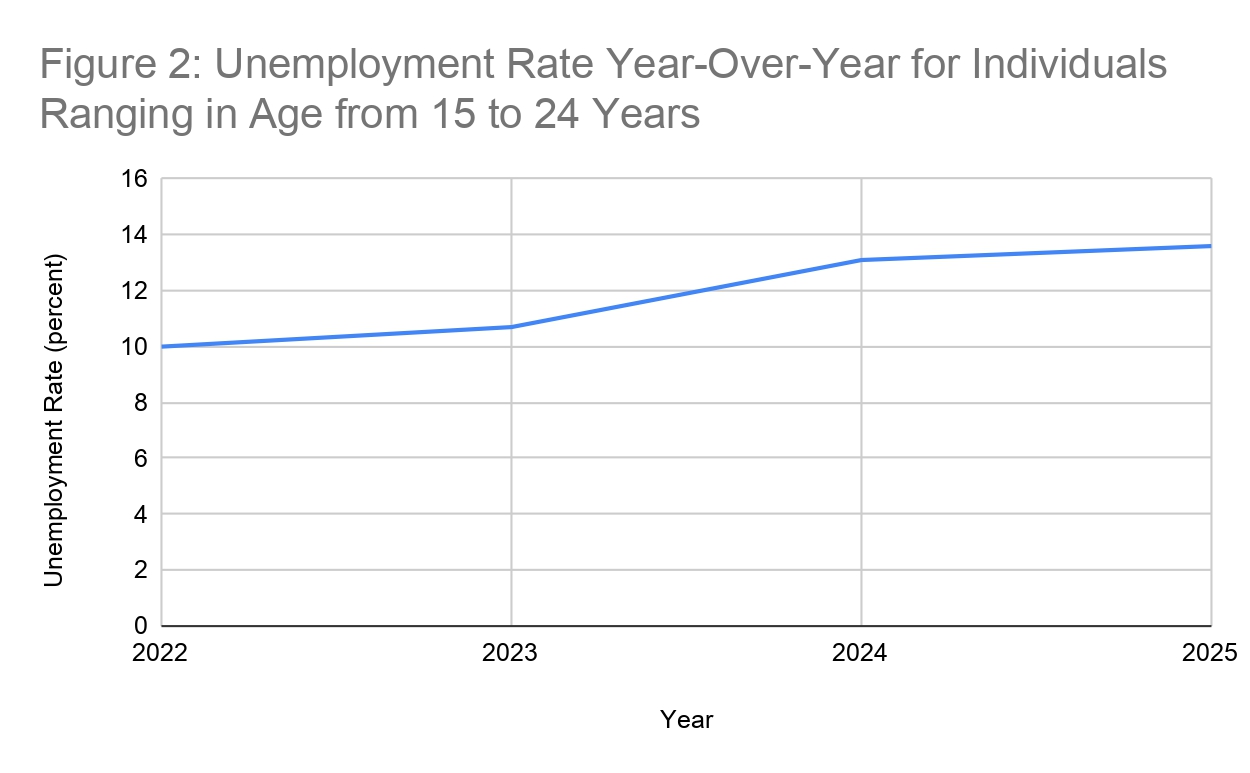

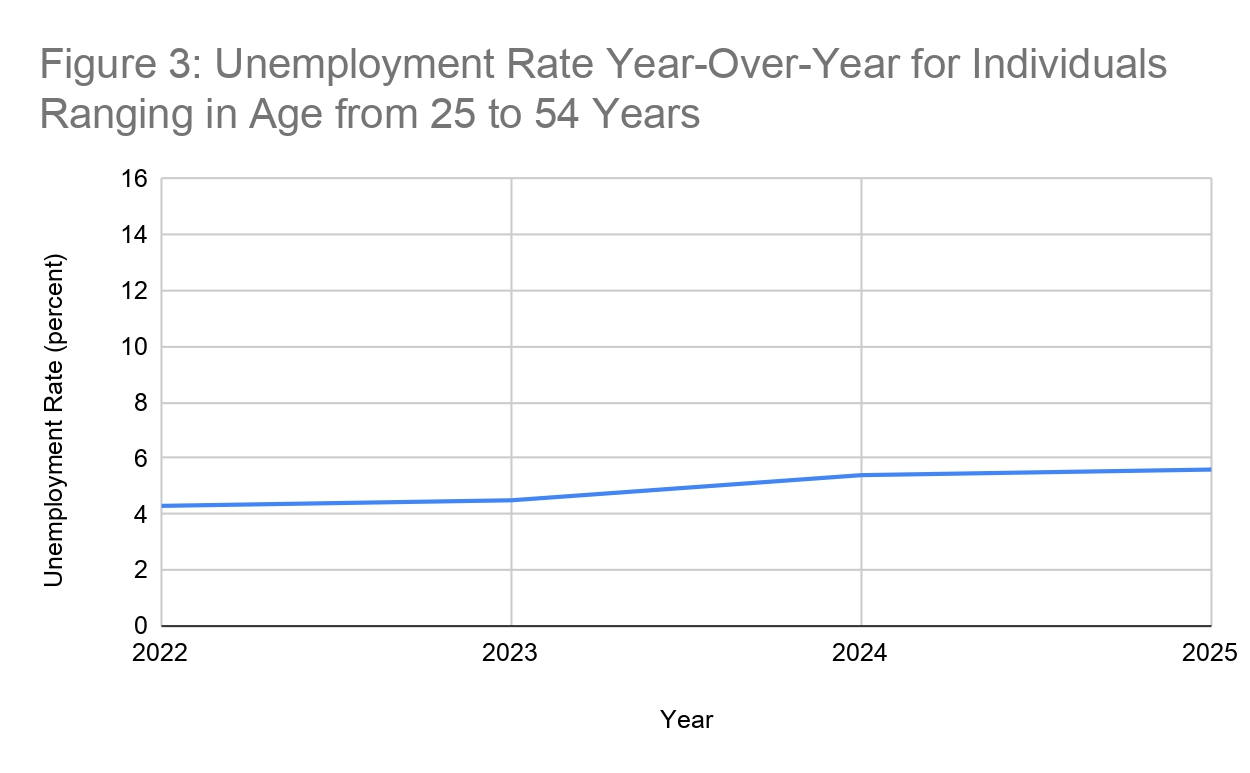

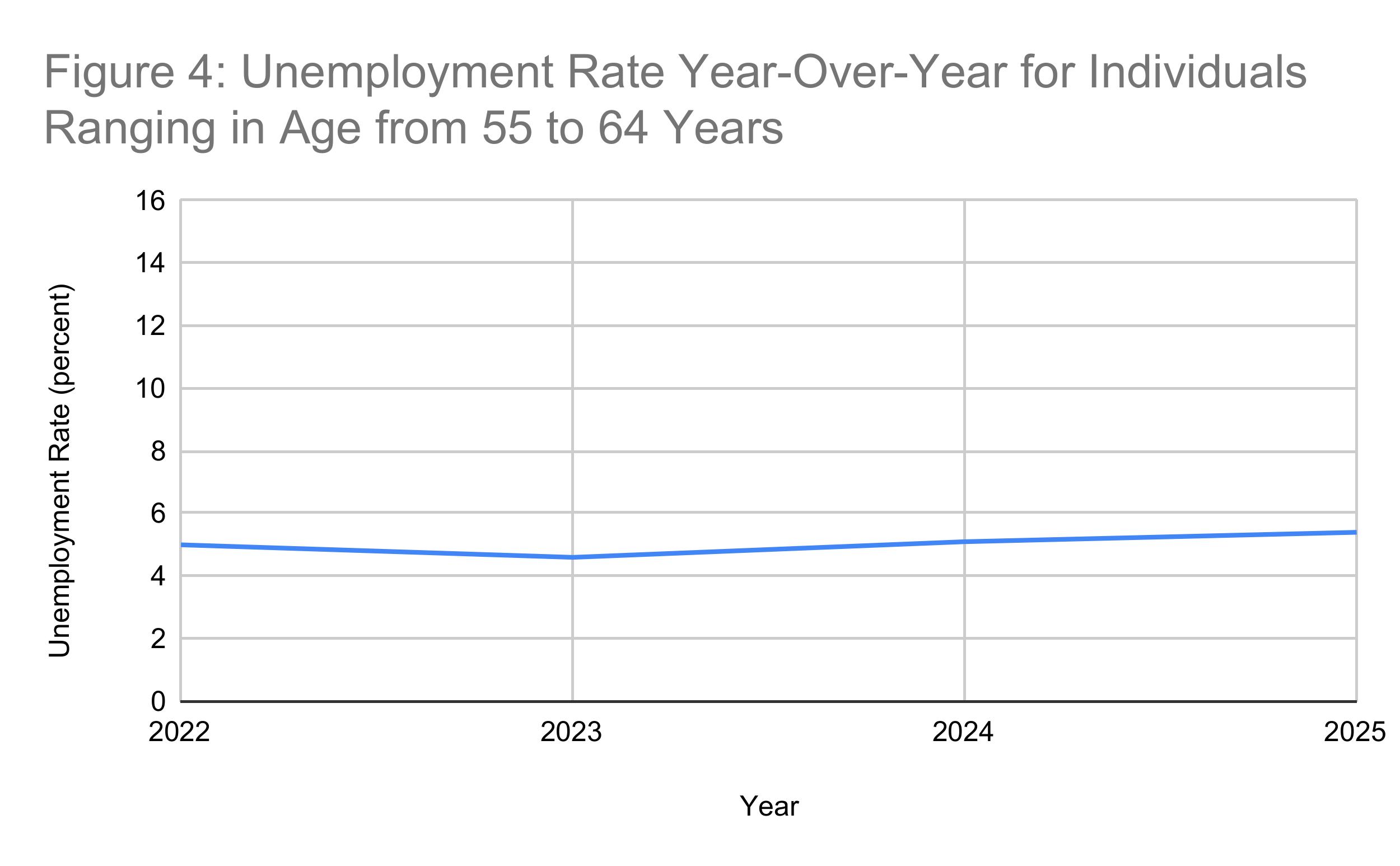

According to Statistics Canada (2018), in 2011, Generation Z “were just starting to enter the labour market.” Five years into their entry, in 2016, the unemployment-to-job vacancy ratio was at 3.4:1– fast-forward another thirteen years, it has reduced to 2.0:1. There as such exists a trend: as Generation Z accumulates in the labour force, so does the proportion of job vacancies. Generation Z, therefore, may be of particular benefit for study since their entry has coincided with the recent labour market changes experienced in Canada. In addition, in further support of this notion, as indicated by Figures 2, 3 and 4, Generation Z is experiencing a more drastic increase in unemployment rate year-over-year in comparison to other working generations (Statistics Canada, 2025). Not only this, but they are the least studied working generation, with Canadian research exploring workplace generation differences between Generation Z and previous generations emerging only as recently as four years ago (Mahmoud et al., 2021).

Figure 2: Canadian unemployment rate over post-COVID years for individuals ranging in age from 15 to 24 years. Since 2022, unemployment for this demographic has increased by 36% (Statistics Canada, 2025).

Figure 3: Canadian unemployment rate over post-COVID years for individuals ranging in age from 25 to 54 years. Since 2022, unemployment for this demographic has increased by 30% (Statistics Canada, 2025).

Figure 4: Canadian unemployment rate over post-COVID years for individuals ranging in age from 55 to 64 years. Since 2022, unemployment for this demographic has increased by 8% (Statistics Canada, 2025).

Currently Circulating Findings and Interpretations of Generation Z’s Workplace Preferences

The topic of Generation Z’s workplace preferences has been captivating, but only in recent years, resulting in empirical research on the subject matter being few-and-far-between, particularly in the Canadian context. As pointed-out by Kowalczyk-Kroenke (2024), multidimensional crises, that is those that foster intersections between financial, political, cultural, social, and environmental strains, affect individuals’ emotions, attitudes, expectations and behavior. The adapted coping methods in circumstances involving rapid change and high uncertainty come to determine an individual’s psychological needs, and consequently, how they will operate in the workplace (Kowalczyk-Kroenke, 2024). In accordance, it is vital that insight on Generation Z’s workplace preferences be grounded in a local context, with Canadians experiencing a unique set of co-occurring large-scale crises in areas such as housing, overdose, mental health, healthcare, education, and both national and international politics.

A study assessing workplace motivation across generations X,Y, and Z through an online survey completed by Canadians between 2017 and 2020 found that Generation Z is more susceptible to amotivation in comparison to X and Y generations (Mahmoud et al., 2021). In the context of the multidimensional work motivation scale (MWMS), which was incorporated within the survey delivered to these participants, amotivation “is defined as a lack of motivation or voluntary intention towards accomplishing one’s work” (Trépanier et al., 2023, p. 158). The study also concluded that, within the workplace context, extrinsic motivation as an overarching motivator is valid for only Generation Z (Mahmoud et al., 2021). Extrinsic motivation relates to societal expectations and values– extrinsically driven individuals perform their duties to receive acknowledgements or rewards (Mahmoud et al., 2020). In addition, the study found that identified regulation, where “one fully recognises and accepts the underlying importance of one’s work as objectives aligned with personal goals and values,” is only effective as a source of motivation for generations Y and X (Trépanier et al., 2023, p. 158). Finally, intrinsic motivation, “where individuals are willing to complete an activity, because they consider the activity interesting and pleasurable,” acts as a more significant contributor to Generation Z’s overall work motivation in comparison to Generation X and Generation Y (Mahmoud et al., 2020, p. 397). With this, from a psychological research perspective, several unique workplace motivation attributes of Generation Z have been identified.

Given that this discourse is still emerging, the majority of existing sources homing in on this discussion are journalistic rather than academic. For instance, through the news outlet, HR Dive, a report of high dissatisfaction rates in North American Generation Z tech workers argues for more opportunities for career development as a strategy for employers to obtain greater engagement and retention of employees (Crist, 2024). This article reported that through a survey delivered to North American tech professionals by the global tech recruitment firm, Lorien, it has been discovered that factors including the use of outdated technology, lack of career progression, and negative company cultures were among the principal reasons why 90% of Generation Z tech workers were motivated for a job change (Crist, 2024). When asked about prioritized considerations in accepting future job offers, it was reported that, in order of prevalence, opportunities for career growth, flexible schedules and higher salaries were weighed heavily (Crist, 2024).

One strong example of an ongoing mismatch between the working conditions of a workplace and those desired by job seekers arises with the ‘Unpaid Work Won’t Fly’ campaign, with which the union representing a majority of Canadian flight attendants is pushing back on the aviation industry by demanding that local candidates and national party leaders ensure fair compensation within this work environment (Unpaid Work Won’t Fly, n.d.). Policies dictating that flight attendants are only to be paid while the aircraft is in the air, and not for their completion of tasks on the ground, or during flight delays, cost workers thirty-five unpaid hours per month (Kwon & Cormier, 2025). Through this campaign, the union presents unpaid ground time as a major dissatisfaction in and of itself, but additionally posits that repercussions to this challenge of excessive unpaid hours, include detriments to mental health and chronic fatigue (Kwon & Cormier, 2025). This narrative within the Canadian aviation industry is pertinent to the discussion of Generation Z preferences in the workplace, with the Government of Canada (2025) positing that in upcoming years, “school leavers are expected to be the main source of job seekers” within the flight attendant profession.

Photograph taken by author when boarding a Canadian commercial airline’s aircraft—flight attendants on board were not paid during this time.

As critical as the involvement of Generation Z in the labour force is, it may at this point be deduced that prior research on this topic is sparse, with firm, all-encompassing conclusions being impossible to make based upon the few case-by-case scenarios that are only recently being brought to attention. The numbers are showing that we have a problem, but we do not yet have answers pointing towards our solution.

Interviewing Canadian Generation Z Individuals in 2025

Grounded in the notion of a mismatch between working conditions dominating occupations and those accepted by job seekers, the present research aims to uncover Canadian Generation Z’s preferences on workplace conditions through interviews with individuals of this demographic who are either soon completing their formal education or in the early years of their career. The results of these interviews present qualitative interpretations that may provide employers with insight on the areas to which operational changes need to be made to attract and retain this generation.

The first of the interviews conducted was with participant T.S. (name redacted), a twenty-four year old working as a police constable. This participant completed a BA in Psychology at the University of British Columbia, a credential exceeding the educational requirements of her workplace (in accordance with the previously outlined data indicating that unemployed Canadians with a Bachelor’s degree or higher exceed the number of vacant positions requiring this level of education). When asked about whether she felt her educational path set her up for success in the workplace, T.S. indicated that she “wouldn’t say that a degree made [her] more prepared for [her] job than any other path would have” (personal communication, March 4, 2025). In terms of the characteristics this participant would prefer in a given professional position, she noted prioritising “… a job with a sense of purpose where… at the end of the day you feel like you really accomplished something,” and a competitive salary and benefits. In addition, T.S. indicated her prioritisation of “… the opportunity for career progression,” as well as perks such as an onsite gym, free employee parking, and electric vehicle charging stations. When asked about the characteristics that would turn her away from a professional position, T.S. emphasized “… a lack of pay transparency,” and employers that lack an online presence and accordingly do not provide sufficient information on their mission.

The second interview was conducted with participant L.O. (name redacted), a twenty-three year old pursuing a Bachelor of Design in Architecture, Landscape Architecture and Urbanism at the University of British Columbia. When asked whether she felt her educational path was setting her up for success in the workplace, she noted, as a co-op student currently working at an architecture firm, that “… there was a large learning curve when entering the workplace,” noting examples such as discrepancies between the softwares primarily used in the industry versus the ones taught during schooling (personal communication, March 9, 2025). When asked about the characteristics she prefers in professional positions, L.O. mentioned the importance of enjoying working with the team one is assigned, being compensated fairly, and feeling competent in her skillset with the potential of being able to develop it further. Interestingly, L.O. indicated that feeling competent in her work not only helps her “feel secure” but addresses the benefit of receiving “…fulfillment… in the people [she is] around.” This speaks to the findings of Mahmoud et al. (2021), where extrinsic motivation, that is that related to achieving acknowledgment or rewards, has a greater influence on Generation Z than other generations. Both participants’ discussions of salary as a factor influencing whether a given job offer may be prioritised, are in further agreement with this finding, especially when paired with participant T.S. stating that a lack of pay transparency would turn her away from a prospective offer of employment. For L.O., when asked about the factors that would cause a job offer to appear unattractive, she noted those that do not offer comprehensive benefits, vacation time, and work-life balance. Additionally, a lack of flexibility in offering remote work would turn L.O. away, just as found by the survey reporting on Generation Z tech workers’ preferences as described by Crist (2024).

Finally, the third interview was conducted with participant N.R. (name redacted), a twenty-two year old pursuing a Bachelor of Science in Interactive Arts and Technology with a Minor in Print and Publishing at Simon Fraser University. This fourth-year student is soon to work in user experience design and user interface design. When asked about whether she felt her educational path was setting her up for success in the workplace, she shared that although her education has taught her the skills she will need in the workplace, it did not prepare her for “…breaking into the professional world and securing a position” (personal communication, March 10, 2025). On the topic of characteristics of a job offer that would call to her, N.R. noted that opportunities for career progression, job security, comprehensive benefits, and work-life balance would take precedence for her. She also added her prioritization of a profession where she would “…truly enjoy the projects [she] work[s] on, and ideally the environment as well”. The latter, again, mirrors the findings of Mahmoud et al., (2021), where Generation Z is more significantly motivated by intrinsic motivation (that where individuals are motivated to complete tasks because they find them pleasurable) than previous generations. Finally, her discussion of characteristics of a job offer that would turn her away revolved around job postings that do not disclose pay, and of “…outdated workplace practices or technology”, which she explained would limit her skills in being transferred to new work environments. Again, this mirrors Crist (2024)’s article on Generation Z tech workers, many of whom considered outdated technology as a reason to leave their workplace.

Discussion

As one would hope, the interviews conducted in this research offer findings useful to employers currently adjusting their recruitment practices to attract Generation Z. Although not entirely reflective of the 2021 study by Mahmoud et al., for instance through participant T.S.’ prioritisation for a job giving her a sense of purpose (which would have been more suited as a motivator for generations X and Y), generally, this investigation’s findings are in agreement with prior research on motivational factors for Generation Z. Moreover, it expands beyond research on motivational factors alone, identifying the exact, concrete priorities of the increasingly working generation. Just as argued by Crist (2024), all three interviewees preferred work environments where there exist opportunities for career progression and felt that compensation is an important factor for consideration. Beyond this, however, the three interviews also all presented the significance of comprehensive benefits for incoming Generation Z employees. Other themes arose as well, although not consistent for all three interviewees. These include the prioritization of primarily, work-life balance, the availability of remote work or onsite amenities such as free employee parking or a gym, as well as enjoying the workplace environment, just as found by Crist (2024) with her report on Generation Z tech workers leaving the industry due to negative company cultures.

For employers, this may mean shifting recruitment practices by disclosing pay, and presenting indications of workplace perks, whether they be offerings of benefits packages, opportunities for remote work, or free employee parking. Other implications from this research point towards effective employee retention strategies, for instance fostering a positive workplace culture, using updated technology, or perhaps, most importantly, offering paths for career progression.

This research, having only assessed three individuals of various work sectors, can merely serve as a starting point for learning about how Generation Z individuals can be best recruited and retained as employees. More than this, the significance of this article lies in its piecing together of Generation Z’s unmet workplace needs acting as a potential contributor to the actively reducing unemployment-to-job vacancy ratio in Canada. Previously, it was written that the numbers are showing that we have a problem, but we do not yet have answers pointing towards our solution– hopefully, with the insights gained from the aforementioned interviews, we may inch closer to finding the right workplace practices to serve the generation now flooding the doors of Canada’s labour market.

References

Crist, C. (2024). Vast majority of Gen Z tech workers say they’d consider new career opportunities. HRDive. https://www.hrdive.com/news/tech-worker-dissatisfaction/715888/#:~:text=About%2090%25%20of%20Gen%20Z,fears%20of%20a%20brain%20drain.

Government of Canada. (2024). Job Vacancy Data for the First Quarter of 2024. https://search.open.canada.ca/qpnotes/record/esdc-edsc,EWDOL2024June12

Government of Canada. (2025). Canadian Occupational Projection System (COPS). https://occupations.esdc.gc.ca/sppc-cops/occupationsummarydetail.jsp?tid=299&lang=eng

Grayson, P. (2021). Boomers and Generation Z on campus: Expectations, goals, and experiences. Canadian Review of Sociology, 58(4), 549-568. https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12362

Kowalczyk-Kroenke, A. (2024). Where Is Generation Z Headed? What Do They Want, What Do They Get, and How Are Generation Z Employees Coping in Times of Crises in the Polish Labour Market? Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology – Organization & Management, 202, 253–267. https://doi.org/10.29119/1641-3466.2024.202.16

Kwon, E. & Cormier, L. (2025). Canadian Flight Attendants are Pushing for Fair Ground Pay Amid Union Negotiations. Trent University News and Events. https://www.trentu.ca/news/story/42099

Mahmoud, A.B., Fuxman, L., Mohr, I., Reisel, W.D. and Grigoriou, N. (2020). The reincarnation of work motivation: Millennials vs older generations. International Sociology, 35(4), 393-414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580920912970

Mahmoud, A.B., Fuxman, L., Mohr, I., Reisel, W.D. and Grigoriou, N. (2021). “We aren’t your reincarnation!” workplace motivation across X, Y and Z generations. International Journal of Manpower, 42(1), 193-209. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-09-2019-0448

Statistics Canada. (2017). Linking labour demand and labour supply: Job vacancies and the unemployed. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2017001/article/54878-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2018). Generations in Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/98-311-x/98-311-x2011003_2-eng.cfm

Statistics Canada. (2022). A generational portrait of Canada’s aging population from the 2021 Census. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/98-200-x/2021003/98-200-x2021003-eng.cfm

Statistics Canada. (2023). Unemployment and job vacancies by education, 2016 to 2022. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/36-28-0001/2023005/article/00001-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2025). Labour Force Survey, January 2025. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/250207/dq250207a-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2025). Unemployment rate, participation rate and employment rate by educational attainment, annual. https://doi.org/10.25318/1410002001-eng

Trépanier, S. G., Peterson, C., Gagné, M., Fernet, C., Levesque-Côté, J., & Howard, J. L. (2022). Revisiting the Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale (MWMS). European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 32(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2022.2116315

Unpaid Work Won’t Fly. (n.d.). https://unpaidworkwontfly.ca/