Ruby Chevalier

Ruby Chevalier (she/her) is completing a Bachelors of Arts with a Major in Psychology at Capilano University. She has appeared on the Dean’s List multiple times. Ruby currently works as a behavior interventionist under Butinga Consulting. She hopes to further her education by obtaining a master’s degree in counseling psychology at the University of Calgary with the intention of becoming a therapist.

Individuals possess unique perspectives shaped by their experiences. Personal lenses enable us to recognize issues that might be overlooked by others. In order to ensure that education is inclusive and accessible to all, the Ministry must be able to build systems from a variety of viewpoints when developing curriculum. Working with children on the spectrum sharpened my awareness of the challenges and realities that autistic children face in the classroom. At a previous daycare position, staff regularly expressed frustration over a child’s perceived high demands in the classroom. The team showed impatience and inflexibility regarding the child’s needs, even questioning the feasibility of them remaining at the center. The facility also couldn’t provide additional support or alternative services when requested.

The Ministry writes and designs a curriculum that assumes that individuals with disabilities, distinctive traits, and limitations do not belong to the collective “we” in classrooms (Diamond & Kirby, 2014, p. 113). According to data from the U.S. Department of Education, 63% of students with disabilities (SWD) in 2017 attended general education classes for 80% or more of the day (Ackerman et al., 2023). According to this data, general education teachers should receive training in order to adopt strategies that cater to the diverse behavioural and complex educational demands of students with particular needs (2). Since these people do not belong to the normative, dominant group, everyone outside of the “we” is seen as working in opposition to the accepted standards in an effort to gain preferred opportunities (Diamond & Kirby, 2014, p. 113). There are varying kinds of people fitting within a broad spectrum of distinctions, variances, and unique characteristics in a given society (2). Accordingly, “everyone” in this society should encompass all identities when used in this sense (2). The practice of inclusion is not an approach solely benefiting a child with unique needs; it benefits everyone within a classroom.

Drawing on my experience as a behaviour interventionist for children with autism, I emphasize positive reinforcement techniques. This involves replacing disruptive behaviours with positive alternatives and ensuring consistency across different environments, such as school and home. I work with youth in daycare and elementary school settings, recognizing and addressing environmental barriers that may impede learning. For instance, providing tools like fidget tools or wobble seats allows children to self-regulate and participate in group activities. Having a separate space apart from the group for when a child feels dysregulated is another environmental accommodation for when a child exhibits intense feelings and is needing a break. Rather than reacting to unexpected actions or conflicts, positive reinforcement strategies focus on teaching individuals tools to prevent, problem-solve, and approach challenging situations positively.

In my work, positive framing and positive praise have a significant influence on whether someone maintains a behaviour or not. This behaviour retention is integral for children, as they are learning about the boundaries of others and how to navigate the social world. In my interview with Morgan Butinga, a Board-certified behaviour analyst, I inquired about the contributions of positive reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative reinforcement to effective behaviour management across individuals and environments. Buitinga, a behaviour consultant, explains during our interview that positive punishment, which refers to adding an unpleasant consequence after a behaviour occurs, has been employed in academic settings oftentimes to withdraw students from their learning environments. For instance, if a student disrupts class, they might be sent to the hall, acting as negative punishment and reinforcement. Such consequences are often seen as negative experiences from an academic and social-behavioural standpoint.

Positive punishment, however, can be useful for skill practice, like running laps to improve stamina. However, as Buitinga, a behaviour analyst, outlines in our interview, when viewed through an academic lens, negative reinforcement and positive punishment, such as removing a student from the learning experience or being asked to wait in a separate space, are unhelpful ways to support their learning. All students in public schools, from early childhood to secondary school, should be encouraged with positive reinforcement for effective behaviour regulation. Avoiding the use of positive punishment and negative reinforcement in classrooms is essential. To foster a cooperative learning environment, British Columbia’s public education system should promote and support students feeling like members of a team.

This is a photo of my Zoom interview with behavioural analyst Morgan Buitinga. Having worked as a behaviour interventionist in the past, Morgan Buitinga is currently employed as a behaviour consultant. Morgan Buitinga has a Masters of Education in Special Education with an emphasis on autism and developmental disabilities, in addition to being a board-certified behaviour analyst. During the interview, I asked Morgan about her experience with behavioural outcomes related to her present position and how positive reinforcement has helped her in day-to-day settings. Additionally, Buitinga shed light on the usage of both positive and negative punishment and reinforcement in educational settings, as well as the reasons behind their potential drawbacks.

Personal Narrative

When I started working with a long-term client in behaviour intervention, the three-year-old non-verbal child on the spectrum displayed challenging behaviours like hitting, kicking, spitting, and biting. The daycare was unprepared for these issues. Initially, our team focused on teaching emotional regulation and communication skills to mitigate these challenges. My role involved implementing the child-specific behavioural plans created by the analyst to manage disruptive behaviours in various classroom situations, like waiting, sharing, social skills, playing with others, and idea sharing. During that time, concerns arose from myself and the other behavioural interventionists about the facility’s punishment methods, including berating children and using harsh feedback while we would go into the facility to conduct sessions. Additionally, the daycare staff suggested using a leg to restrain the child during naptime. For example, I was advised by the daycare staff to place one leg across a child’s chest during naptime, allowing the child to position their arms and placing another leg across their lower body to restrict movement. I also observed how this posture was kept in place despite the child’s protests or struggles (i.e., crying).

According to the aforementioned standards, using restraint is inappropriate in this situation. Additionally, any form of restraint on a person lying on the ground is strongly discouraged in physical management or safety training, as it poses a risk of compression asphyxiation to the chest, sternum, diaphragm, back, or abdomen. However, little explanation was provided by the daycare staff as to why they used this technique. The family reported the misconduct to Vancouver Coastal Health Child Care B.C. licensing. The options for justice were limited, prompting a move to a new centre and the possibility of filing a new claim if the family stayed at the current centre, and more instances arose. The plan was to transfer the child to a different daycare for a better experience and community support in line with the family’s and intervention team’s goals.

After the transition, the child rarely exhibited challenging behaviours for communication. Instead, they improved their self-expression through tools like chewelries, visual communication boards, fidgets, and sensory aids. These behaviours were effectively managed at the new centre, mostly arising in uncomfortable situations or significant life transitions. Positive staff support contributed to significant progress, minimizing reactive behaviours that would typically arise only at times when the child felt unheard or faced firm language, triggering memories from the previous centre.

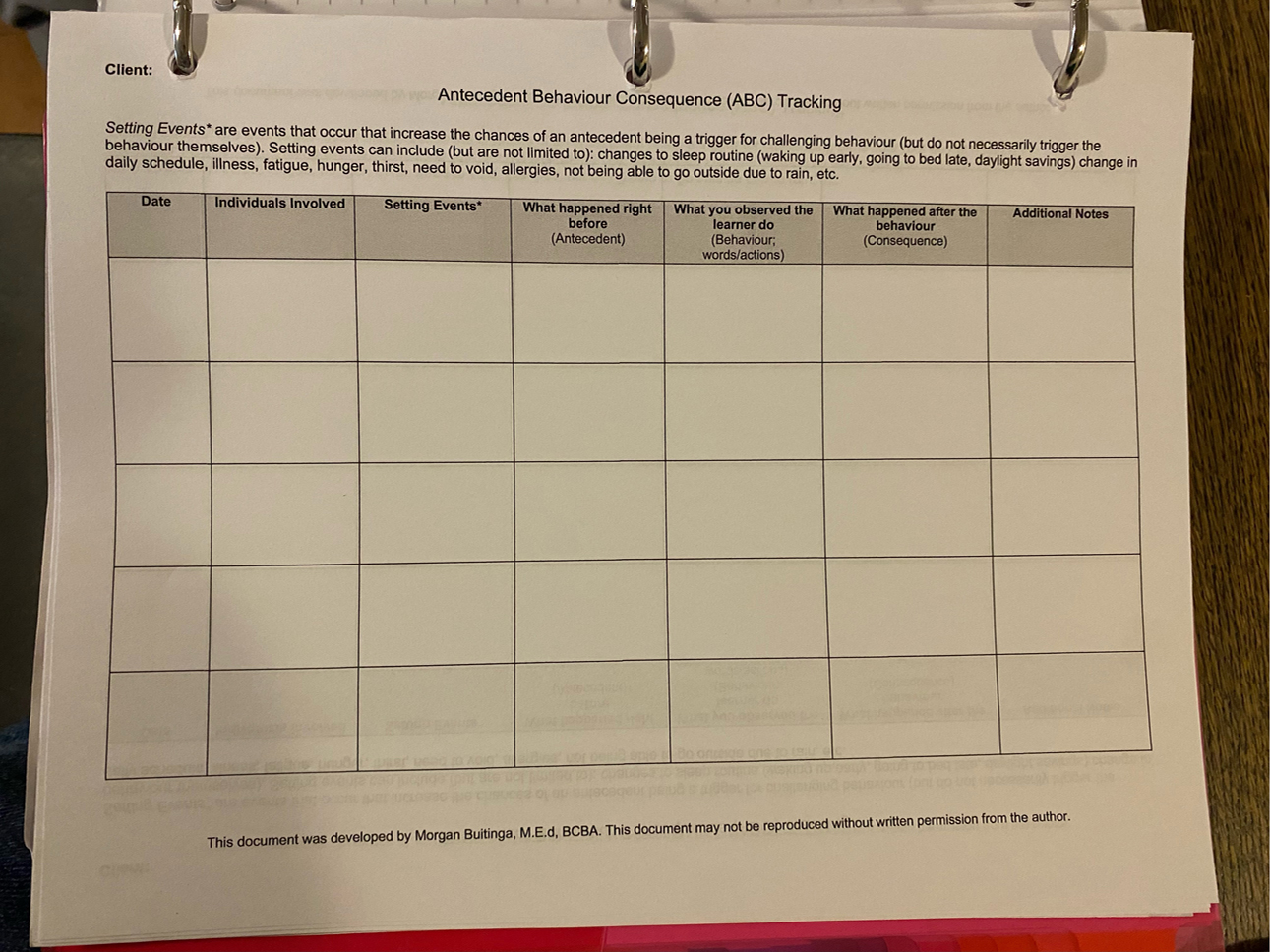

This is a picture of an ABC tracker that I use in my work as a behaviour interventionist. ABC tracker stands for antecedent: what triggers the behaviour; behaviour: the action; consequence: what happens directly after the behaviour occurred. This is a form of tracking how behaviours manifest in ABA, particularly if we are unsure of why a behaviour is occurring. ABC trackers can give some context to challenging behaviours. This allows behaviour analysts to understand why particular behaviours are happening and can allow us to provide a child with more specific intervention strategies. This tracking can also allow support staff to see if a behaviour is common across environments.

Primary Research

Working with children on the spectrum has revealed how teachers often exclude and undervalue those with unique needs, despite some positive initiatives by the British Columbian government. While there are government-backed efforts and additional training for aspiring teachers, there’s still a significant gap in implementing protocols and making informed decisions in the daily educational environment. In behavioural intervention, motivating daycares and employees to adopt optimal practices for children on the spectrum can be challenging, even though these practices can be beneficial for children with various behavioural needs. In my interview with Kathleen Kummen, a Capilano University Early Childhood Education faculty member, the discussion focused on pedagogical approaches in the context of British Columbian education, positive reinforcement, inclusiveness, and teaching barriers. Kummen, a Capilano instructor, explains during an in-person interview that we are advocating against people who care deeply but have little to no formal education, so these challenges persist and obstruct informative teaching. Kummen, an early childhood education expert, reveals during an in-person interview that we enter pedagogical settings where sometimes what one person thinks is significant is not relevant to another. My work in behaviour intervention has brought to light the ways in which people with disabilities are often viewed as outsiders in need of additional support from a system unable to offer it. Kummen, a professional in pedagogical practice, asserts during an in-person interview that the inability to mandate a four-year degree for those dealing with young children is one of the challenges facing early childhood educators today.

In my interview with Kummen, a specialist in pedagogical practice, she emphasizes the need for implementing common measures, like improved literacy rates and high school graduation rates, in the field. This differs from Canada’s expectations, where early childhood educators, as outlined by Kummen during our interview, are often highly gendered, racialized, and economically precarious. The early learning and child care (ELCC) workforce is disproportionately made up of women, visible minorities, and non-native speakers of official Canadian languages (Choi & Frank, 2023). Research indicates that women from minority ethnic groups in the US working as child care providers often occupy low-paying entry-level positions with limited prospects for professional growth and decision-making authority (6). Furthermore, individuals in both general and special education settings are susceptible to severe caregiver burnout, leading to brief experiences with students in need of consistency and routine. This underscores key themes: professionals in these fields may struggle to commit due to various stressors (e.g., housing instability, communication challenges, lack of education); they may lack the capacity for prolonged commitment; lack of motivation in feeling undervalued in their work; and insufficient preparation in research-informed teaching practices. Visible minority ELCC workers, compared to non-visible minority peers, were more likely to be paid employees, yet more likely to be impoverished (6). The percentage of visible minority groups earning at least $40,000 was lower than that of the white population (7). In light of these findings, early childhood educators and teachers are not well-equipped to respond to inclusion measures due to systemic issues.

The predominant educational approach in many British Columbian schools continues to be a standardized curriculum with the aim of teaching to the green [the presumed, mythical, average, and homogenous student] (Moore, 2020). This method of teaching aims to reach the majority of students with one standard approach—the green way (7). For kids that require additional guidance, we then attempt to take a different approach, but this tends to happen after the fact (7). Kummens, an expert in curriculum and pedagogy, highlights during our interview how education has become an ethical project: “Because we really have not talked about inclusion; it’s about nicing people who are OK enough to be present […] with ill-defined inclusive practices”. Teachers have exceedingly challenging duties as a result of this retrofit strategy, especially when multiple students may require this kind of curriculum modification (Moore, 2020).

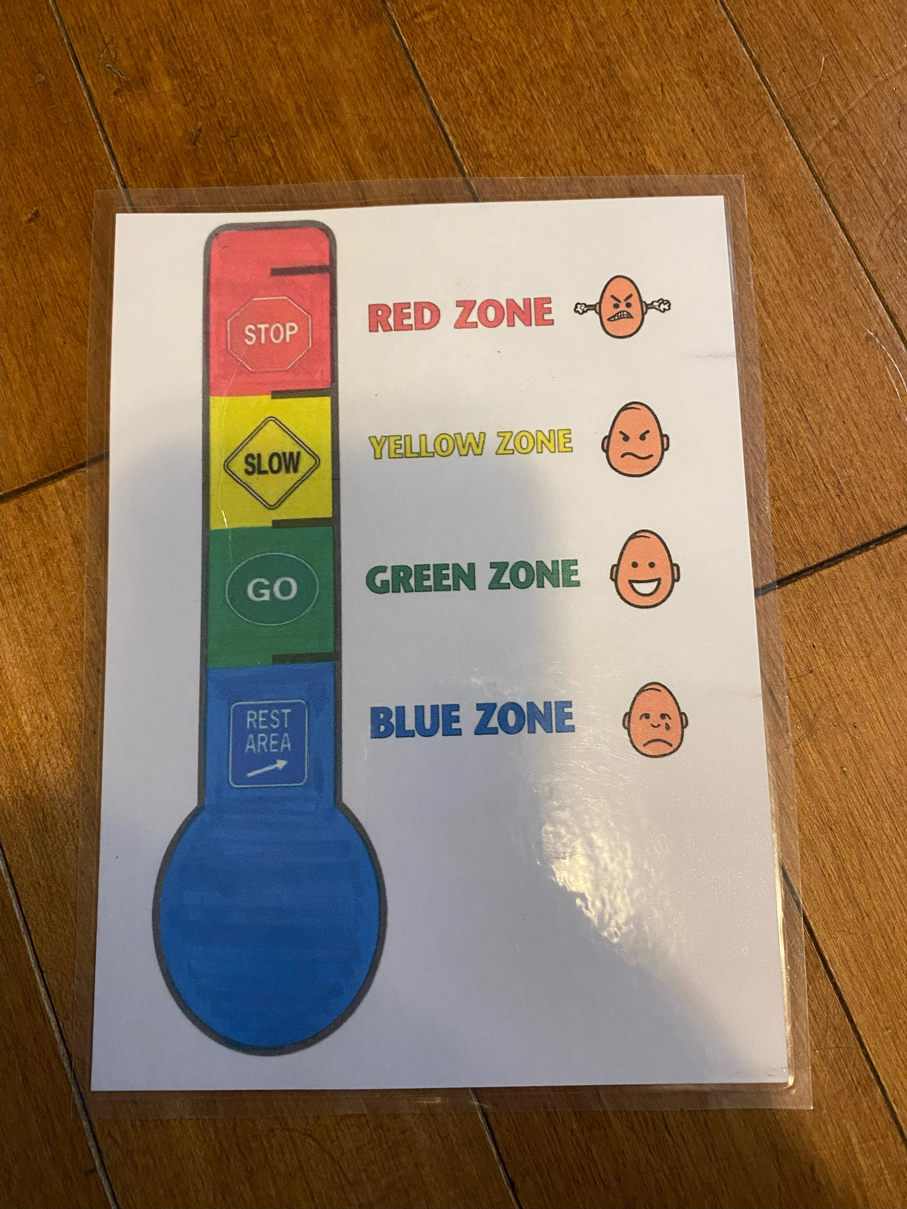

This image depicts an emotional thermometer tool. This image serves as a visual representation of the regulatory zones. Children can learn to identify and classify emotions as they arise, as well as comprehend the range of emotions they are experiencing. Additionally, this gives behavioural interventionists the means to draw attention to and characterize the feelings that a client in treatment may be experiencing or may be causing others to feel. With the help of this visual, learners may assess and identify their emotional state as it occurs. This emotional thermometer aligns with the tools in the program zones of regulation.

One contemporary solution to this problem is the use of individual education plans. A student with special needs may have an Individual Education Plan (IEP), which is a written plan that outlines their unique goals, any necessary adjustments or revisions, the services they will receive, and how their progress will be monitored (“Individual Education Plans,” 2022). However, these require a lot of time and resources. Teachers may prefer limiting the number of students needing individualized attention to reduce their classroom workload, presenting a challenge in promoting inclusivity while managing reasonable workloads (Moore, 2020). In accordance with Kummen’s explanation during an interview, a scholar on pedagogy says there is a “need for a collective education plan; we also need space so that fewer individual education plans are necessary.” Inclusion aims to change existing structures and services, not force individuals into societal norms (“Diane Richler”, 2023). Schools must give students and families the chance to participate in shared decision-making, exercise autonomy, acquire assistance, and have their identities and strengths valued (Whiteley, 2023).

Based on my experiences in behaviour intervention, children with autism in centres often face reprisals from educators and lack crucial support to achieve their developmental goals. Many centres, while presenting themselves as disability-friendly, prioritize appearances over genuine inclusivity. The standard of education in the twenty-first century should ensure people of all genders, abilities, ethnicities, socioeconomic backgrounds, and ages acquire the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes for resilient and responsive societies (“Why Inclusive Education”). Yet, reachers and other educators who hold conservative views about education may be opposed to inclusion because they believe that individuals with disabilities are not as valuable as those without disabilities (Kirjava & Witham, 2022).

At one daycare, prioritizing picture-taking of children during activities took precedence over meeting their immediate needs, often neglecting licensing regulations. The goal was to showcase the centre’s diversity, including neurodiversity and ethnic diversity, through these photos. In conformity with Kummens description, a thought leader in early childhood practices, in our learning environments, “Children are less than humans; we don’t see them as having the same comforts and aesthetics that adults need to go to work, and we don’t see the women that work with them requiring these things either. In agreement with Kummen’s view, as discussed in an interview, “The system itself is a barrier to inclusion.” Institutionally, schools can create social contexts that, from an early age, give kids the impression that they are part of a welcoming community and that their accomplishments are valued, encouraging active and meaningful participation.

This picture is of me working alongside a client in behaviour intervention. The interventions I use in my practice vary according to the requirements of the child I am working with. In some aspects of my work, I teach children more concrete life skills and communication, while in other areas, I focus on teaching them more specific goals, like starting prosocial behaviour and assessing children on what they should expect in certain situations, such as “expected or unexpected” actions or “public and private” actions. Given that frustrating or unexpected events are a part of life, the range of programs provided can assist in transforming a child’s thought patterns to see experiences positively.

Particularly since public school classrooms are becoming increasingly heterogeneous, the public education system in British Columbia needs to support and cultivate conditions where young students are encouraged to feel like members of a team, fostering an atmosphere of cooperative learning. According to Buitinga’s illustration, for a professional in applied behavioural analysis (ABA) implementation, positive reinforcement and praise can be incorporated into daily life situations. Buitinga, a specialist in ABA, notes during an interview that establishing positive relationships with others can be achieved by simply being nice, expressing appreciation, and recognizing the acts that someone contributed that were beneficial.

From my experience working in childcare centres, a lot of young children are disciplined in learning environments using outdated techniques, such as ordering a child to perform an action or behave a certain way just because an authority figure told them to (“do x because I said so”). These traditional ways of engaging with students (i.e., those in preschool, elementary, secondary, or post-secondary education), such as the use of corporal punishment, may lead people to disregard the intent behind one’s action and only attribute meaning based on their physical experiences. In my experience with a child with autism in a facility emphasizing negative reinforcement, there was a focus on outward behaviour rather than motivation, discouraging reflective thinking. For instance, the student was forced to endure loud music in a classroom and sought a break in a closet, as it was the most nearby isolated space to calm down. While attempting to reintegrate the child using intervention strategies, a teacher sternly instructed them to leave the space, using strong language and applying excessive pressure on their arm, undermining positive approaches.

As stated by Buitinga during an interview with an expert in behaviour analysis, children who receive negative reinforcement frequently develop low self-esteem and lack the confidence to be open-minded and share their particular perspectives and ideas with others. This may be extremely frustrating for those affected and can result in an array of internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Historically, children have had limited influence over the teaching and learning methods employed in their educational journey. Therefore, to promote effective behaviour management strategies for all students, public school settings need to provide positive reinforcement to every student, from childcare to secondary school. Students should not be subjected to positive punishment or negative reinforcement in the classroom as a means of disciplinary action or as a tool for behaviour management.

Research and Theoretical Framework

History of School Discipline

Using rhetoric that connected physical violence to homosocial contact, male educators could define a real man’s persona in the 1960s and construct an authoritarian teacher ideal (Hedlin, 2013). Women’s employment in Sweden caused controversy in the 1960s (10). Studies conducted by the government recommended that women actively participate in the workforce in order to support welfare state growth and economic sustainability (10). Teachers’ Journal disproved the idea that women shouldn’t hold jobs by establishing a connection between parenting, work, and femininity (10). In contrast to the cliché of the uncaring working mother, women presented themselves as nurturing educators, encouraging a positive femininity that encompassed working with children (10).

Classroom Environments

Due to obstacles including a lack of professional development opportunities, resources, support, and/or training preparation, a large number of general education teachers are inexperienced and unequipped to provide effective instruction to SWD (Ackerman et al., 2023). According to Rohmah Faristin et al. (2022), there is a 92.8 percent contribution between learning outcomes, feedback, and learning motivation. Research has shown that learning motivation is positively correlated with both positive reinforcement and feedback, accounting for 93.2 percent of the connection (Rohmah Faristin et al., 2022). Using the principle of operant conditioning in psychology, B. F. Skinner established how a behavioural repertoire is chosen, formed, and maintained by its consequences (Overskeid, 2018). People’s sensitivity to consequences determines their capacity to adjust, frequently unconsciously, to the circumstances in which they find themselves (11). These findings illustrate the necessity of adapting instruction and teaching practices to meet the demands of all kids in the classroom, including neurodiverse students and students with particular needs.

Teaching Attitudes

Typical classrooms often lack positive reinforcement for good behaviour, as research suggests teachers focus more on addressing misconduct than verbally praising appropriate conduct (Nelson & Kauffman, 2020). The prevalent use of negatively reinforced instructions relies on aversive consequences for undesirable behavior, assuming students will be deterred by the prospect of unpleasant outcomes (11). Teachers believe this approach reduces problematic behaviour and minimizes the need for harsh consequences (11). However, it inadvertently highlights disruptive behaviour, indicating to students that attention is garnered only through misbehaviour, potentially encouraging more instances of such conduct to seek teacher attention.

Positive Reinforcement Techniques

Since challenging behaviour makes it difficult to learn and to make the transition to adolescence and early adulthood effectively, a number of school-based programs and preventive interventions have been developed globally with the goal of reducing disruptive behaviour in schools (Jensen, 2021).

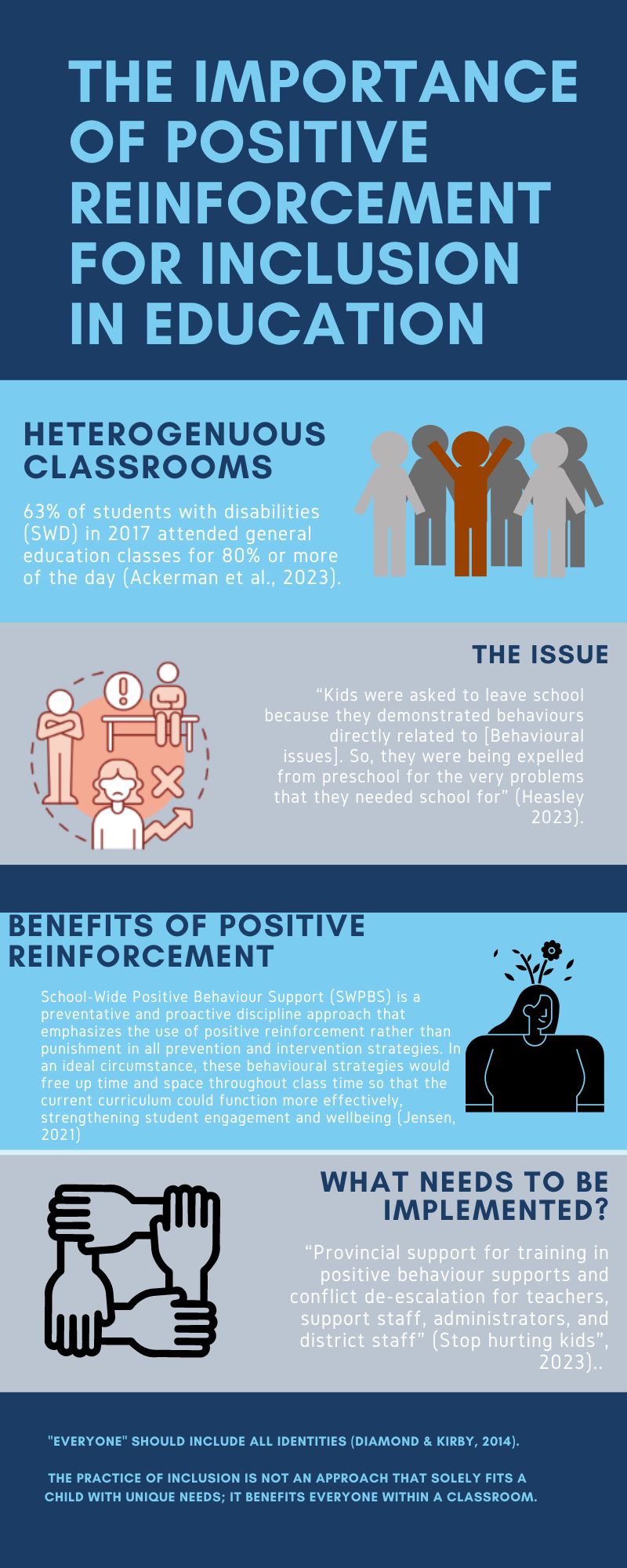

The insightful quotes in this graphic can aid in educating the general public about the advantages of positive reinforcement in B.C. school settings. This infographic focuses on the condition of today’s classrooms, the causes for their challenges, and the integration of positive reinforcement in educational environments. The primary ideas I discuss in this paper are outlined in this infographic, which also illustrates why it makes practical to incorporate positive behavioural supports into BC’s educational institutions. To make the information easier to understand, this infographic highlights the most crucial points I make in the article and includes graphics for each of the major themes.

Programs and Outcomes

A study conducted at UBC discovered that the method utilized in all behaviour modification studies is relevant and helpful to educators who have prior experience creating lesson plans and customizing education for each student. With this method, teachers implement curriculum in which the environment’s control over the learner is less restrictive and more flexible to student needs (Main, 1972). According to this research, the educator’s focus and support of appropriate behaviour while ignoring unsuitable behaviour have a substantial effect on students’ academic achievement (12).

The Zones of Regulation is a social-emotional learning curriculum that is frequently used in school settings (Mason et al., 2023). The Zones of Regulation curriculum is an educational framework that teaches self-regulation abilities that are practical in everyday situations (12). Positive mental health techniques, a social-emotional learning framework, and trauma-informed approaches contributed to the creation of the program (12). The Zones of Regulation curriculum was initially designed for students with neurobiological and mental health disorders, such as oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), Tourette syndrome, ADHD, and ASD; however, it is also beneficial to a wider range of students (12). Students in preschool, elementary, and secondary schools are using the Zones of Regulation curriculum, which has gained popularity as an educational strategy (12). The effectiveness of the Zones of Regulation for students with any diagnosis label cannot currently be empirically analyzed due to a lack of research available (12). While the Zones of Regulation program is widely utilized and recognized in educational institutions, programs with broad appeal may inherently be regarded as legitimate without additional critical examination of their execution or results (12).

Within a trauma-informed framework, the MindUP for Young Children project implements and assesses an evidence-based, mindfulness-informed social-emotional development intervention (“MindUP for Young Children,” 2023). This program is a global, school-based education approach that integrates positive psychology, neuroscience, and mindful awareness in 15 teacher-led courses (13). In order to solidify the application of the MindUP teachings to their daily lives, parent-child sessions have also been developed (13). In order to maintain awareness and responsiveness in their interactions with their students, instructors can benefit from the MindUP program (13).

Conclusion

In childcare, I have observed antiquated ways of discipline, instructing children to obey authority rather than considering alternative and collaborative approaches. Outdated techniques of discipline in childcare settings frequently involve giving commands to children based solely on authority without taking their motivations into account. This method places outward appearances above awareness, implying that coming to decisions based solely on what has happened outwardly is of greater importance than taking rationality into account. Teachers in general education may not have the skills or resources necessary to instruct students with disabilities due to issues such as inadequate professional development, resources, and assistance (Ackerman et al., 2023). Teachers in British Columbia face heavy workloads, especially with retrofitted education methods, hindering inclusivity and reasonable workloads (Shelley, 2023).

To truly be inclusive, we need to improve our structures and educational processes so they benefit everyone (Richler, 2023). Kummen, a childhood education specialist, states during our interview that our existing systems “put all the problems in the child; they don’t look at the environment; they don’t look at the social injustices; they don’t look at all the problems that impede their progress; and they don’t look at what needs to be created in order for this child to thrive. As described in an interview by Kummen, a professional in childhood education, “We lack the ability to ask ourselves, How can I listen to this child’s communication style to possibly lessen the need for me to yell for help?” Our curriculum should include positive reinforcement techniques like MindUp, Zones of Regulation, SWPBS, and environmental customization in an effort to support inclusion.

Since it can be challenging to control what is taught in many external settings, such as public schools, teachers have various opinions on how to discipline children, some of which are more traditional and use harsh language. From a psychological standpoint, these harsh strategies could model negative reinforcement in an educational setting, which can contribute to the continuance of attention-seeking and disruptive behaviors. As posed by Kummen, an early childhood learning professional, during an interview, how do we create room in the world for diverse ways of being and get over the idea that the only life that is truly worthwhile is one in which the individual essentially fits the stereotype of what constitutes normalcy? According to Kummen in our interview, an early childhood development specialist, education encompasses more than just acceptable behaviour; transformational thinking needs to be the focus in education, calling for difference and diversity of thought. All students, from daycare to secondary school, should experience positive reinforcement in school settings.

The education system in British Columbia needs to offer teacher training programs that address classroom environment construction and behaviour management. Rewarding the entire class along with individual students for valuable contributions to the class or acting in accordance with individual goals is an integral part of implementing SWPBS, but it is not consistently applied in settings where SWPBS is already in use. In SWPBS, integrating student empowerment is crucial. Staff must demonstrate responsiveness and reflexivity to cater to individual and group learning dynamics. Reflexivity is also essential for those implementing SWPBS for thoughtful and adaptive execution. In the case of the child I supported as a behaviour interventionist, envision an educational setting where all children’s needs are heard without judgment. Within this setting, students are encouraged to meaningfully participate in class and are not drawn attention to their shortcomings or negative behaviours. Staff members working in the general facility provide additional support to children who need it, eliminating the need for additional resources and allowing educators to address ways they can enhance their instructional methods. Though it has not historically been recognized as an essential component in educational settings like daycare facilities, elementary schools, and high schools, communication is an integral function of daily life.

References

Ackerman, K. B., Whitney, T., & Samudre, M. D. (2023). The Effectiveness of a Peer Coaching Intervention on Co-Teachers’ Use of High Leverage Practices. Preventing School Failure, 67(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2022.2070591

Chapter Five: Individual education plans (IEPS). Inclusion BC. (2022). https://inclusionbc.org/our-resources/inclusive-education-handbook-chapter-5/#:~:text=An%20Individual%20Education%20Plan%20%28IEP%29%20is%20a%20documented,Manual%20of%20Policies%2C%20Procedures%20and%20Guidelines%20by%20BC

Choi, Y., & Frank, K. (2023). Diversity, economic characteristics, and retention of early learning and child care workers in canada. Journal of Research in Childhood Education. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1080/02568543.2023.2232832

Diamond, S., and Kirby, A. (2014). “Trans jeopardy/trans resistance,” in B. LeFrancois and S. Diamond (eds.), Psychiatry Disrupted: Theorizing resistance and crafting the (r)evolution (pp. 163-176). Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press.

Diane Richler: Jewish Federations of Canada – UIA. Diane Richler | Jewish Federations of Canada – UIA. (2023). https://www.jewishcanada.org/speakers-and-presenters/diane-richler

Gage, N. A., Grasley-Boy, N., Lombardo, M., & Anderson, L. (2020). The effect of School-Wide Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports on disciplinary exclusions: A conceptual replication. Behavioral Disorders, 46(1), 42–53. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1177/0198742919896305

Hardy, J. K., & McLeod, R. H. (2020). Using positive reinforcement with young children. Beyond Behavior, 29(2), 95–107. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1177/1074295620915724

Hedlin, M. (2013). Teachers and school discipline 1960–1970: Constructions of femininities and masculinities in Teachers’ Journal. Education Inquiry, 4(4), 232-20. https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v4i4.23220

Jensen, S. S. (2021). Effects of school-wide positive behavior support in Denmark: Results from the Danish National Register data. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 32(2), 260–278. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1080/09243453.2020.1840398

Kirjava, S. A., & Witham, K. (2022). Practical and ethical considerations for neurodiversity inclusion in audiology education and practice. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 29, 1–4. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1016/j.tine.2022.100185

Main, G. C. (1972). The effects of positive reinforcement and a token program in a public junior high school class (T). University of British Columbia. Retrieved from https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubctheses/831/items/1.0101647

Mason, B. K., Leaf, J. B., & Gerhardt, P. F. (2023). A Research Review of the Zones of Regulation Program. Journal of Special Education, 1. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224669231170202

Moore, S. (2020). Supporting inclusive and responsive learning environments video series. Ministry of Education and Child Care. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/k-12/teach/resources-for-teachers/inclusive-education/videos

Nelson, C. M., & Kauffman, J. M. (2020). A commentary on the special issue: Promoting use of positive reinforcement in schools. Beyond Behavior, 29(2), 116–118. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1177/1074295620934707

Overskeid, G. (2018). Do we need the environment to explain operant behavior? Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00373

Rohmah Faristin, Yuniawatika Yuniawatika, & Sri Murdiyah. (2022). The Relationship between Positive Reinforcement and Learning Outcomes Feedback in Increasing the Learning Motivation of Fifth-Grade Students. Sekolah Dasar: Kajian Teori Dan Praktik Pendidikan, 31(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.17977/um009v31i22022p127

United Nations. (n.d.). Why inclusive education is important for all students. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/transforming-education-summit/why-inclusive-education-important-all-students#:~:text=Truly%20transformative%20education%20must%20be%20inclusive.%20The%20education,and%20attitudes%20required%20for%20resilient%20and%20caring%20communities.

Western University. (2023). MindUP for Young Children. Western Centre for School Mental Health. https://www.csmh.uwo.ca/research/mindup.html#:~:text=The%20MindUP%20program%20helps%20educators%20learn%20how%20to,funded%20by%20the%20Public%20Health%20Agency%20of%20Canada.

Whiteley, S. (2023). Educator researcher: Dr. Jess Whitley. Mysite. https://www.jesswhitley.ca/