Tara Ward

Tara Ward is currently completing her Bachelor of Arts Degree in Interdisciplinary Studies and isinvolved in overseeing the editorial process for the 2024 edition of Capilano University’s literary journal, The Liar. She has a keen interest in publishing and editing, which she aims to integrate with her passion for creative writing. Tara has consistently demonstrated dedication to excellence, earning multiple appearances on the Dean’s List. Additionally, she works part-time as an aide in her local school district, showcasing her commitment to education and community engagement. Tara plans to pursue a Bachelor of Education in the coming year, aligning with her goal of becoming an elementary school teacher. Her academic and extracurricular achievements highlight her commitment to personal and professional growth, positioning her as an aspiring educator ready to make impactful contributions to the field of education.

“Despite differences in the definition of inclusion and the education required to become a teacher, [they] are not adequately prepared to teach in inclusive classrooms.”

-Umesh Sharma and Jahirul Mullick

The introduction of Article 24 – Inclusive Education, which states every student is welcome to attend their neighbourhood school, no matter their additional educational and behavioural needs, has left British Columbia teachers and educational assistants in crisis. As special needs students filter into local districts under the misguided notion of inclusion, British Columbia’s Ministry of Education and Child Care has neglected to predict the damage Article 24 would cause to the British Columbian education system; they have also failed to address the issues which have arisen. However, this is not to say that these students need to be segregated or stigmatised; instead, we must find an agreeable and flexible solution that will benefit all British Columbian students. Inclusion in classrooms is essential; however, due to Article 24 – Inclusive Education, all students are suffering, particularly the diagnosed and undiagnosed special needs students that Article 24 was created to protect. Furthermore, this ineffective inclusion system pushes teachers and educational assistants to their breaking point, forcing them to obtain Ukeru self-defence training as more special needs students enter their local districts. Although there are potential solutions, such as Shelly Moore’s The Ideal Model, BC’s educational system worsens, resulting in education professionals balancing more high and low-incidence students while simultaneously adapting the BC required curriculum to meet the needs of all their students.

If Article 24 had been introduced earlier, it would have negatively affected my entire family: my profoundly deaf sister, my teaching mum and myself, a diagnosed dyslexic. As I began preparing for my Bachelor of Education,compos I gained work experience in a local district. I witnessed the understaffed, overworked, and undertrained educators and the affected students, which made me curious, as well; having been affected in high school by a teacher strike surrounding class sizes and compositions, I was perplexed why classrooms remained the same, yet class sizes continued to grow.

Article 24 overrules a Canadian Supreme Court ruling regarding class composition, further amplifying the teacher and education assistance shortage. As this overruling will affect my future career path, I wanted to understand, leading to much research and conducting two interviews with affected teachers, who will remain anonymous. My interviewees were diverse enough to gain a vast understanding of this ongoing situation. Teacher A is new to elementary school teaching but not to education. In contrast, Teacher B is a seasoned teacher in an elementary school, having worked in elementary and high school education for over 20 years across multiple schools and districts. These interviews provided a plethora of information, specifically Teacher B pulling from her twenty years of experience, highlighting how the new education system overrides classroom composition, offering only the poor alternative of remedy time, “compensation for the school district breaking the collective agreement, i.e., going over the class composition limits” (Teacher B), and ignoring teacher burnout, the Canadian government has inadvertently forced teachers to choose between their students, inevitably leading to exclusion within BC classrooms.

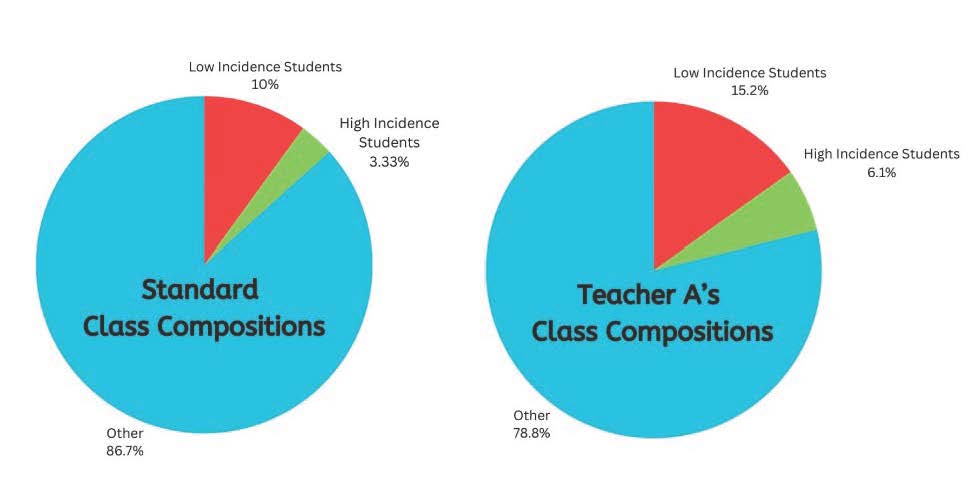

These pie charts compare what the standard class composition should look like in a BC classroom, dictated by the Ministry of Education, as published in “Teaching in Inclusive Classrooms: Efficacy and Beliefs of Canadian Preservice Teachers,” and what Teacher A current classroom’s composition is, which goes against Canada’s standard classroom composition.

Article 24’s mandate to improve inclusive education is “…based on the principle that all children should learn together, wherever possible, regardless of difference” (Lattanzio, Andrews, and Wilson, 2015). Created to cater to special needs students and their families, “Parents of children with disabilities face many challenges, but few as great as ensuring their children get a good education” (Galloway). This intention of this progressive step to remove the barriers is essential, as the estimated number of “… students with special education needs in Canada rang[ing] from 9% to 15%” (Canadian Council on Learning), leaving inclusive education as a significant concern within the Ministry of Education. However, while inclusive education held promise in theory, implementing Act 24 has fallen short of expectations, reflected in the little progress made since the act was introduced. Officially, this slow progress is attributed to the “…obstacles still to be removed and supports to be developed and funded. Each province and territory in Canada has work to do to fulfil the promise of the Convention. Inclusive Education Canada is working to meet this challenge” (Inclusive Education).

The slow progress can be attributed to the individual districts having to devise strategies to fund inclusive education alone, as each district became responsible for revising its budget and education programs to cater to the influx of students with disabilities. Outside of funding, the sluggish advancements towards inclusive education are linked to the disregard of BC’s standard class composition, “…the collective agreement guidelines [which] dictate[s] each classroom only has 10% low-incidence students, 3 out of 30 students, and 3.333% high-incidence students, 1 out of 30 students, in a single class” (Bennett). This ratio was created to maintain a manageable classroom environment. As more high- and low-incidence students are incorporated into their local districts, the more this ratio is being ignored.

Teacher A was adamant about explaining the definition of high- and low-incidence students, as these distinctions were a relatively new concept to them as they were new to education. “High Incidence” designations are special needs students with a designation with a “high incidence.” This includes those with learning disabilities like dyslexia or dysgraphia” (Teacher A). Whereas “Low Incidence are special needs students that happen less often in a population – these include designations around physical disability (like diabetes), Downs Syndrome, Hearing and Sight impaired and some Autism Spectrum Disorder” (Teacher A). As a class’s composition becomes more complex, classrooms become chaotic. With the limited funding, resources, and support, teachers are suffering, verbalised by Teacher A, “It’s exhausting- we don’t have enough support whether from EA, LST or straight up time to find diversified resources” (Teacher A), hindering all their student’s education.

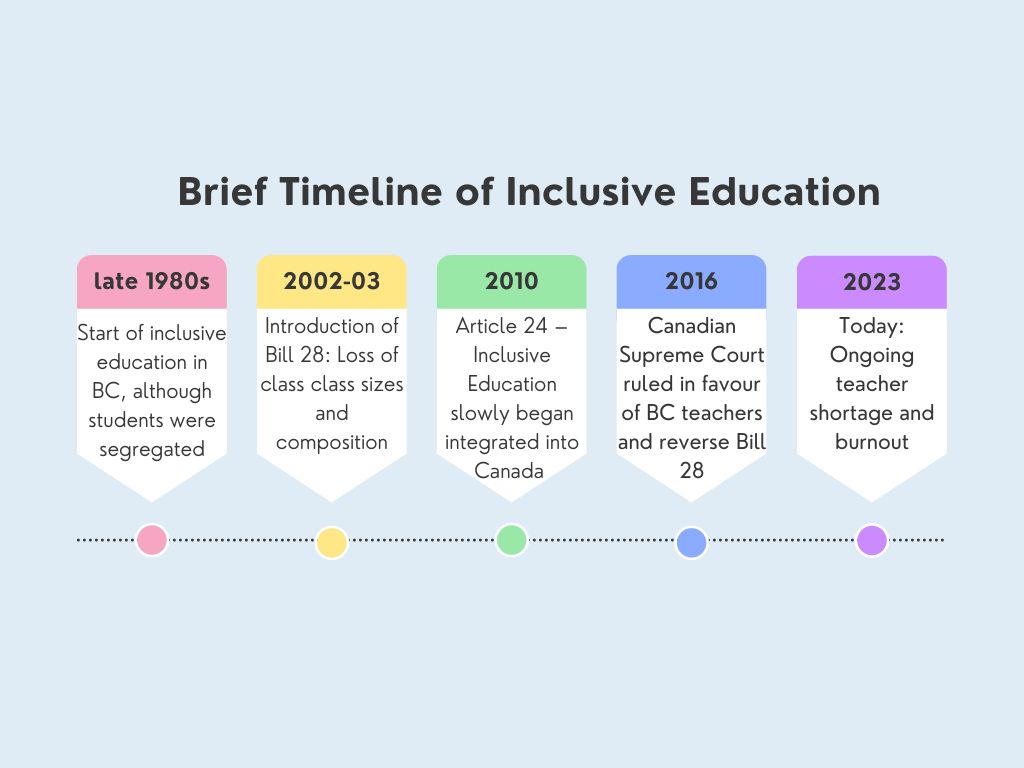

This Brief Timeline of Inclusive Education breaks down how Inclusive Education has changed over time within Canada and how it has been intertwined with other Bills and Acts throughout BC Education.

Class composition is critical within classrooms, to the extent that the British Columbia Teacher Federation (BCTF), British Columbia’s teacher’s union, went to the Supreme Court to cement class composition into Canadian law. After maintaining steady class composition for years, the BCFT lost control in 2002 with the introduction of Bill 28, which “…substantially reduced the scope of teachers’ bargaining [power]. It explicitly provided that the employer’s right to determine matters including class size and composition” (BCTF). Although Bill 28 was framed as cost-cutting measures, in actuality, Bill 28 was “… an attempt to finally end what had been an ongoing struggle between governments of all stripes and the BCTF for control over what the government regarded as matters of managerial discretion and public policy, and which BCTF considered vital bargaining issues representing teachers’ fundamental working conditions” (Slinn).

Bill 28 stripped educators of their control over class sizes and composition, leading burnt-out teachers to go on strike, which led to the groundbreaking Supreme Court of Canada ruling on November 10, 2016; the Supreme Court ruled in favour of the BCTF after BC teachers went on strike to reverse Bill 28. “The government should not have done that back in 2002, and it’s pretty amazing for the Supreme Court of Canada to agree with that and to issue that decision in the room right when we were sitting there,” said BCTF President Glen Hansman after the favourable verdict. After winning the right to dictate class sizes and composition, teachers regained control; however, with Act 24 and the introduction of more special needs students into schools, classrooms have moved further away from an acceptable composition.

Furthermore, many as-of-yet undiagnosed students in classrooms require the same assistance as their diagnosed classmates; however, these undiagnosed students cannot access the same funding, forcing classroom teachers to step out of their role, as these students cannot access education assistance. Additionally, undiagnosed students do not count towards the high or low-incidence student ratio within a class’s composition; as Teacher A stated, “I expect I’d have at least one or two more Low incidences and at least one High incidence in my current class” (Teacher A), which are not counted towards their class composition.

Sometimes, these undiagnosed students are immigrants, as their families frequently only get their children diagnosed once they receive their permanent residency or citizenship, making the process easier for the families (Teacher B). This choice forces schools, after Act 24, to accept undiagnosed students with severe learning and behavioural disabilities, knowing the lack of funding and support they will receive. These undiagnosed students’ erratic “… behaviour can also take away education assistance’s time from the students who need the academic and social emotional support but remain calm in the lessons” (Teacher B). The only other alternative is for their teachers to assume the role of educational assistant while attempting to teach the rest of their class simultaneously. Due to this additional workload expected of teachers and educational assistance, overloaded class compositions, and the lack of funding or other support, the profession is experiencing an increase in burnout, leading to an overall educational staff shortage. Our teachers are being pulled too thin, and many are choosing to walk away before they break.

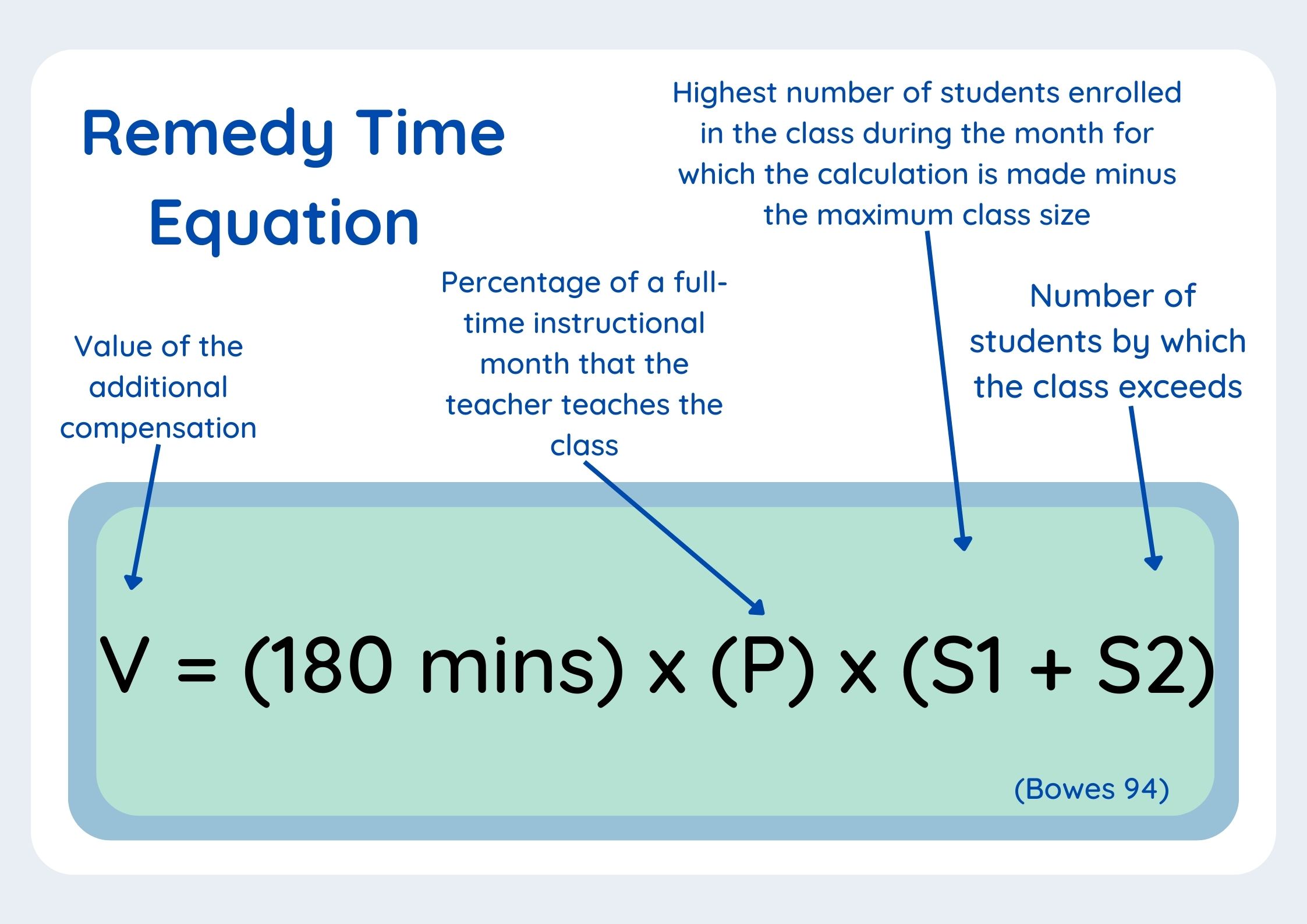

To partially maintain the Supreme Court’s 2016 ruling and teachers’ teaching ability, the Ministry of Education created remedy time to rectify the classroom compensation imbalance. Remedy time is awarded to the “Teachers of classes that do not comply with the restored class size and composition provisions” (Bowes 94). The teachers whose classes violate class composition “…will become eligible to receive a monthly remedy [time] for [the] non-compliance” (Bowes 94) of class composition. Created “…as a way to try to give Teachers time to manage the overload of work required by having diverse, high needs in their classroom” (Teacher A), remedy time offers a calculated amount of minutes per month when a teacher is permitted to request coverage for their class “once the value of the remedy has been calculated” (Bowes 94). To calculate a teacher’s remedy time, their school administrator uses the formula: “(V) = (180 minutes) x (P) x (S1 + S2)” (Bowes 94). This equation looks at a teacher’s class composition, and with every violation, the teacher is awarded remedy time.

Each teacher can choose how to use their awarded remedy time, including “Additional preparation time for the affected teacher; Additional non-enrolling staffing added to the school specifically to work with the affected teacher’s class; Additional enrolling staffing to co-teach with the affected teacher; Other remedies that the local parties agree would be appropriate” (Bowes 94-95). The creation of remedy time indicated that the Canadian government knew there is a problem within our education system; remedy time is an ineffective band-aid on a massive issue, not the solution.

A significant factor when calculating remedy time is the amount of additional low and high-incidence students teachers have in their classes; however, no matter the remedy time awarded, Teacher A reflects that “There is no way to schedule in enough time back to account for the daily time spent managing increased workload, class disruptions, parent communication, behaviour management, resource preparation, lesson adaptations and modifications” (Teacher A). Moreover, many teachers choose not to utilise their awarded remedy time, often driven by a strong sense of guilt associated with leaving their classrooms in the temporary care of another teacher hired to cover their remedy time. Teachers frequently grapple with guilt as the media constantly bombards them with shameful articles: “Do B.C. teachers really need 15 days of sick leave per year that accumulates without a maximum?” Written by Charlie Smith and “BC Teachers Need a Reality Check on Wages and Benefits” by Niels Veldhuis and Peter Cowley. Within these articles and more are accusations and criticisms that are devastatingly harmful to a teacher’s mental health. Lacking a comprehensive grasp of the daily challenges that teachers contend with—belittling statements such as, “If the B.C. Teachers’ Federation wants to generate some public goodwill, it should offer to give up… sick days” (Smith); journalists are gradually turning the public against the teachers. The public shaming surrounding teacher’s paid sick days, a necessity for anyone, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic, taking additional time away from their classrooms becomes unfeasible. Remedy time is a subpar correction and has not made the impact hoped, leaving many teachers to choose to walk away from education, leading to a teacher shortage and worsening classroom conditions as “The failure of teachers to return to their schools has immediate consequences for students and schools” (Gilmour).

The graphic above expands on each element of the Remedy Time Equation, as defined in the Provincial Collective Agreement, which came into effective July 1, 2022, to June 30, 2025. This equation is how a teacher’s remedy time is calculated each month.

The limited support for teachers has left them feeling abandoned. While there are solutions to British Columbia’s teacher shortage, better educational funds increasing teachers’ pay, training and the Ministry of Education better support their educators, as “…higher levels of self-efficacy, or who report that they feel more prepared to meet the requirements of teaching, experience less burnout than teachers who do not feel confident in their skills” (Brouwers & Tomic, 2000; Pas et al., 2012; Ruble et al., 2011), these solutions are complex and costly. However, if action is not taken soon, the shortage will only worsen, as reports show that “…teachers [are] leaving the profession after five to 10 years on the job, citing additional workload and pay as reasons why.” Reid Clark, the president of the Chilliwack Teachers Association, stated (Turner). This affects everyone, particularly students; as Clark adds, “We often see teachers…pulled left, right and centre to cover classes, to cover those vacancies, and the ones impacted are the students and families” (Turner). Although not the only reason for the teacher shortage, Act 24 has inadvertently worsened the issue: “Student behaviour problems in the classroom… increases job demands and leads to prolonged stress or burnout for teachers that eventually leads teachers to move to schools with more resources or leave teaching entirely.” (Aloe et al., 2014; Feng, 2009).

While special needs students are the focus of inclusive education, many forget to consider the other students in the classroom, who also have the human right to education. With the push to integrate special needs students, classrooms are becoming more dysregulated, leading to classroom environments becoming chaotic and unsafe for others as “…teachers, EA and other children witness violence in their classrooms” (Teacher B) as a result of special needs students. An experienced Teacher A details, “The hallways are loud and full of screaming kids, and the risk of violence is everyday and completely normalized. If you ask most people, they don’t go to work everyday expecting to be hit, yelled at or something thrown at them at some point.” (Teacher A). This level of disruption leads to “…academics [being] very low because the classes are being disrupted, evacuated or held hostage by a violent student” (Teacher A). Due to specific student safety plans, classroom equipment such as scissors, pencil sharpeners, and rulers are prohibited from being kept in classrooms for all student’s safety.

This image is a real example of the restrictions teachers must place on classroom supplies. Due to a student’s safety plans, baskets such as this are kept behind teacher’s desks, and only brought out when needed and when classes are heavily supervised or absent.

Whole classrooms are frequently disrupted and forced to relocate to empty classrooms, the school library or the gymnasium for their safety, while a dysregulated classmate’s outburst is attempted to be de-escalated by education assistants and teachers. To avert this, schools often decide to isolate special needs students from their classmates; an experience a young student with autistic and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) experienced as “Ninety per cent of his time when he was at school that first year, he was in the sensory room” (Hyslop). Although sensory rooms are a helpful tool within schools, as they provide a safe and quiet space for students away from the overstimulation of schools, they are not a replacement for a classroom. As these disruptions transpire within elementary schools, students immediately accept, accommodate and empathise with their classmates, regardless of the continuous distortion to their education. Although this empathetic behaviour towards their classmates is commendable at this age, the normalisation of harmful behaviour within classrooms is cause for great concern, something Teacher B discussed throughout her lengthy career in education: “…violence is just another thing they have in their lives at school,” as it is expected to get kicked, punched and hit weekly by students. Although normalisation is necessary to maintain classroom control in response to incidents, it is increasingly unjust for students wanting to learn. As violence from special needs students continues to escalate, education assistants are finding it necessary to obtain Ukeru training.

Ukeru, a “trauma-informed and hands-off approach” to educational training, offers four programs specialising in; “Verbal and nonverbal communication to convert/divert an aggressive individual; Physical release techniques that keep both client and caregiver safe; Physical redirection to avoid injury and self-harm; and Safe Blocking—the only trauma-informed, restraint-free blocking technique” (Training). Ukeru also produces specific mats created to protect teachers and educational assistants and “… to help violent students. There are times when an EA will enter [a] teaching space carrying one or two because the child has been violent earlier in the day.” (Teacher B). These mats are becoming essential to schools as students’ dysregulated outbursts become “…commonplace in schools” (Teacher B). Ukeru mats are not exclusive to British Columbian schools; “… it’s hard to walk 20 feet without seeing Ukeru material anywhere. It’s part of the classrooms, hallways, homes, and even outside” (Zinniel).

The alternative to educational assistants utilising Ukeru training is sending dysregulated students home or preventing them from regularly attending and disturbing classes, denying students their human right to education, an extreme Teacher B has been forced to do, “We had a student start mid-term last year, and after one day we realised they were not yet able to be in the classroom without being violent; additionally, we did not have the EA support or resources to work with the student. It was decided that this student would come for 2.5 hours a day and work 1:1 with an EA, overseen by the LST” (Teacher B). This is not an isolated incident across Canada: “Over 270 parents self-reported…that their disabled children were excluded from school more than 4,700 times in the 2021-22 school year” (Hyslop). Schools struggle to balance including special needs students and protecting every student’s safety and education. If all students have the equal right to access education, as Act 24 states, dysregulated outbursts disrupting students’ education are unjust; similarly, it prevents special needs students from attending classes. Another intricate facet of inclusive education for which only partial solutions exist.

The images above are Ukeru mats, commonly left outside classrooms for easy access when needed. The handled are for the use of the teacher and/or education assistant to grip when a dysregulated student begins hitting and kicking. As staff members are not allowed to touch children even if they are assaulting them these mats are required to protect the student’s rights and physically protect staff members.

One potential solution spearheaded by Shelly Moore, a Canadian educator, researcher, and expert on special education, is prominent in her The Ideal Model concept, where she proposes transforming the current idea of inclusive education into a more adaptable model and optimising its application to education, where inclusion is not seen as a special education program and instead as a concept of teaching everyone. Moore explains that instead of continuing with the current system, which forces teachers to choose the students they help, the system should be adapted so that teachers can help them all. Drawing a metaphor between bowling and teaching, Moore elaborates, “The [bowling] ball is the lesson, the pins are the kids. We aim for the middle. We do the best we can. The pins left standing often have another chance to get to them, but at the end of the day, those two pins staring back at you are the kids who need the most support and the kids who need the most challenge. So, we end up choosing one, and the other one is left standing” (Moore). The purpose of Moore’s bowling metaphor is to explain how we can change our education model to stop teachers from choosing between those last two pins and instead train them to achieve the perfect 7-10 split, but it takes training. Going further, Moore explains that she believes we must shift our thinking of students with disabilities. Instead of seeing and treating them as individuals who need fixing, removing this barrier and replacing the standardised learning system with a standard-spaced learning system and standard-based goals, we can realise that curricular goals are designed to be conceptual and accessible (Moore).

A core element of Moore’s work is “The barrier to inclusion is not kids’ capability levels” (Moore); it is that “…we cannot make things accessible” (Moore). However, Moore is vocal in her support of the Canadian Ministry of Education moving away from special needs schools for students and into district schools, Act 24, intending to create a total environment of inclusive support, which Moore believes will help all students. However, by eliminating specificity-catered schools for special needs students, the Ministry of Education is making education less accessible for many and “forcing students into a classroom when it is not the best place at that moment for them is ableism” (Teacher A). Instead of focusing on inclusive education, we need to prioritise what students need to thrive, which could be “…special schools that can have appropriately paid and trained staff for the violent behavioural kids. [Teachers] are not trained properly and do not have the support in the regular stream for this – and teachers and kids are getting hurt and being traumatised on a regular basis” (Teacher A). In a less extreme example, my sister only thrived in school after moving to The British Columbia Provincial School for the Deaf. She was born profoundly deaf and is classified as a low-incident student. After several years of attending our local district elementary school alongside me, she moved to the School for the Deaf, where she thrived. Although attending a special needs school out of her district goes directly against the ideals of Moore and Act 24, it was the best decision for her, as she was in a classroom with other deaf and hard-of-hearing students and was taught in a practical way that suited her specific needs. While this does not fall under the definition of inclusive education, as her class was created and exclusive to deaf and hard-of-hearing students, it was what they needed to succeed, as “…regular classrooms are not necessarily the best place for all students” (Teacher A).

An alternative solution to Moore’s, proposed by Teacher A, is “…to have full time [educational assistants] (i.e. work 8-4 or 9-5) rather than the 27.5 hours max they work a week” (Teacher A). This would allow teachers time with the educational assistant “before and after class to help photocopy, organize materials, set up lesson plans” (Teacher A). This increase in hours would enable educational assistants to be present more; as Teacher A notes, “Our [educational assistants] cannot support us at all…because they are only present when students are, and there is no extra time” (Teacher A). While seriously helping teachers prepare for classes, this solution “might also attract more EAs to the job as it might realistically be a job that could support a family” (Teacher A).

Act 24 is causing more harm than good. By encouraging dysregulated students into unprepared schools, Act 24 is forcing teachers and educational assistants to work overtime trying to maintain a safe, regulated classroom; however, educators are being subjected to violence, leading many to leave education. The normalisation of violent behaviour in elementary school, which the Ministry of Education continues to expose their teachers to, has created a new reality that Teacher A noted consists of “…getting hit, bit, kicked, rock thrown at your head, whipped across the face with a headphone cord, chair thrown at you, classroom destroyed, relentless noise all day” (Teacher A). Act 24 continues to create an unsafe and defective educational system, and although “…teacher education programs have a crucial responsibility to prepare and graduate teachers who are capable of effectively teaching in these inclusive classrooms” (Specht), this issue cannot be shouldered by educators alone. While all aspects of inclusive education continue to spark debate, Teacher A emphasises that “Students need to be in school,” leaving British Columbia with no easy solution. However, things need to change; if not, teachers’ and students’ suffering will continue, classrooms will no longer be about education but a beginner’s course in combat training, and the next generation will be able to spell dysregulated before understanding osmosis.

References

Aloe, A. M., Shisler, S. M., Norris, B. D., Nickerson, A. B., & Rinker, T. W. (2014). “A

multivariate meta-analysis of student misbehavior and teacher burnout.” Educational Research Review, 12, 30–44. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2014.05.003

BCTF, Negotiations 2001 to 2002, 2008, http://bctf.ca/AboutUs.aspx?id=18888&printPage=true

(1 October 2023); bcpsea obtained an lrb interim order enjoining the planned illegal strike (bcpsea, [2002] bclrb No. B34/2002, upheld on judicial review: “Hospital Employees’ Union v. Health Employers’ Assn. of British Columbia.” 2007 bcsc 372.

Bowes, L. (2023, March 10). “Provincial collective agreement – July 1, 2022, to June 30, 2025.”

Canada Commons. https://canadacommons.ca/artifacts/3494500/provincial-collective-agreement/4295048/

Brouwers, A., & Tomic, W. (2000). “A longitudinal study of teacher burnout and perceived self-efficacy in classroom management.” Teaching and Teacher Education, 16, 239–253. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00057-8

Canadian Council on Learning. 2009. “Does Placement Matter? Comparing the Academic

Performance of Students with Special Needs in Inclusive and Separate Settings. Lessons in Learning.” Accessed October 1st, 2023. http://www.ccl-cca.ca/pdfs/LessonsInLearning/03_18_09E.pdf.

Gilmour, A. F., & Wehby, J. H. (2020). “The association between teaching students with disabilities and teacher turnover.” Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(5), 1042–1060. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000394

Hyslop, Katie. “Disabled Kids Excluded From Education.” The Tyee, 12 July 2023, https://thetyee.ca/News/2023/07/12/Disabled-Kids-Excluded-From-Education/.

Inclusive Education. Inclusion BC, n.d., https://inclusionbc.org/our-resources/what-is-inclusive-education/.

Lattanzio, R., K. Andrews, and J. Wilson. 2015. “What’s the Law: Legal and Policy Implications of Service Provision and Inclusion?” Presented at how to meet the diversity challenge in the classroom, Kingston, Canada, March 31.

Moore, Shelley. “Teaching For All Learners, with Shelley Moore” | Podcast Ep. 8 – Teach Away. https://www.teachaway.com/blog/inclusive-education-with-shelley-moore

Sharma, Umesh, and Jahirul Mullick. “Bridging the Gaps Between Theory and Practice of Inclusive Teacher Education.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1226.

Slinn, Sarah. “Structuring Reality So That the Law Will Follow: British Columbia Teachers’ Quest for Collective Bargaining Rights.” Labor / Le Travail, volume 68, fall 2011, p. 35–78.

Smith, Charlie. “Do B.C. Teachers Really Need 15 Days of Sick Leave a Year to Accumulate Without a Maximum?” Straight, www.straight.com/news/713061/do-bc-teachers-really-need-15-days-sick-leave-year-accumulate-without-maximum.

Specht, J., McGhie-Richmond, D., Loreman, T., Mirenda, P., Bennett, S., Gallagher, T., Young, G., Metsala, J., Aylward, L., Katz, J., Lyons, W., Thompson, S., & Cloutier, S. (2015). “Teaching in inclusive classrooms: Efficacy and beliefs of Canadian preservice teachers.” International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1059501

Teacher A. Interview. Conducted by Tara Ward. 26-31 October 2023.

Teacher B. Interview. Conducted by Tara Ward. 25-29 October 2023.

“The Current with Matt Galloway.” The Current, CBC Radio, 29 Apr. 2014.

“Training.” Ukeru Systems, 5 May 2021, www.ukerusystems.com/how-we-can-help/training/.

Turner, Abigail. “B.C. teacher shortage a ‘really severe crisis,’ union president says.” CTV News, Sept. 6, 2023 https://bc.ctvnews.ca/b-c-teacher-shortage-a-really-severe-crisis-union-president-says-1.6550866

Zinniel, Johnathon. Https://Www.Ukerusystems.Com/Wp-Content/Uploads/2021/04/CaseStudyChildea.Pdf, Ukeru, 2021.

Zussman, Richard. “BCTF wins Supreme Court battle over class size and composition” | CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/bctf-wins-supreme-court-battle-over-class-size-and-composition-1.3845620?utm_source=EdCan+Wire+%2F+Le+Fil+%C3%89dCan&utm_campaign=9943a89ff5-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2018_02_07&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_53657416d3-9943a89ff5-