Mira Golembioski

Mira Golembioski (they/them) is a Fourth-year student at Capilano University, studying creative writing within the Interdisciplinary Studies program. They have published a short story in The Liar, Capilano University’s student-led literary periodical, and have served as part of its editorial team. In the Summer of 2023, they represented Capilano University while studying at Aichi Gakusen University in Okazaki, Japan.

Plagiarism, offensive content, appropriation of the voices of the dead – art generated by Artificial Intelligence (AI), only recently popularized, already has a bad reputation. The cultural connotations of automation are that an old process will be made obsolete by a high-tech replacement, so AI technology appears to be an existential threat to art as it is traditionally practiced. It’s not surprising that some artists are hoping to protect their careers through stricter regulation, for example through the expansion of intellectual property rights (Clarke). In one case, the companies behind multiple AI platforms are facing a lawsuit filed by illustrators whose work was used to program the software, alleging that these platforms’ learning processes “violate the rights of millions of artists” by harvesting data from their works without permission (Chen).

Because of its controversial reputation, AI art needs to be fairly evaluated as its own medium – it has been praised or criticized as only an alternative to art made by humans, despite its totally dissimilar creative process. Part of the fault lies with the way AI art is marketed and even how it is trained. However, its potential does not need to be restricted to imitations. This article seeks to critically interpret AI art on its own terms, to understand how it challenges our definition of art, and to argue that true freedom for artists will not come from regulation but from ensuring that every person has free and equal access to generative AI technology.

Part 1: Excess, Materiality and its Challenge to Quality

“It’s Over, Isn’t It” was supposed to be a romantic song from the cartoon alien Pearl to her dead lover, Rose Quartz. The original video was released on Youtube as a promotion. However, it’s now been joined by a surprising crowd of other singers. Far from the solemn moment intended by the original, it’s possible to find everyone from the livestreamer Markiplier to the necromantic voice of Frank Sinatra attempting their own versions. This slightly irreverent display is, of course, all powered by AI (Enderia).

This proliferation of slight variations is characteristic of the post-AI social media landscape. Music is only one medium in which this tendency is noticeable. One video featuring the song “Bad Apple!!” recreates its music video through AI ‘paintings.’ Each image is, when paused, a unique pastoral image of trees and whitewashed castles; when the video is played, however, they create an animation with moving silhouettes formed from the lighter and darker spaces of the paintings (KF2015). By themselves, these paintings would remain unconvincing pastiches. However, the visual trick into which they are incorporated transforms their large quantity into a powerful aesthetic asset.

In his book Retromania, music critic Simon Reynolds writes in critique of the mass-content practices of then-contemporary 2011 Youtube, which he sees as detrimental to creativity and innovation (56-63). In a mostly pessimistic chapter, he blames the massive volume of content these platforms preserve for the directionlessness which they induce (76-77). He sees their contents as largely composed of “cultural carrion” (63), decontextualized decay which actually decreases creativity by limiting the space and need for innovation (74).

Despite the differences between these media, Reynolds’ negative description of mass content platforms is even more applicable to the world of AI art. What platforms like Youtube feature as a side-effect of their construction, AI intensifies and makes an aesthetic attribute of the material it generates: speed, quantity, and incoherence. Reynolds’ critique is a deep and perceptive attack on those qualities, and reading it allows us to understand the difference between the artistic value systems of traditional and AI art.

Reynolds’ primary concerns are originality and coherence (62-63). Both of these are under threat, he argues (76-77) from what could be called the excess of digital platforms, which accumulate incoherent content with little oversight. (The word “content” is important here, because it suggests physicality, an almost inhuman mass, unlike “art” which is gauzy and ethereal.) On Youtube and similar platforms, content is not ranked by quality, and material from the past is scattered together with that from the present (63). Like an over-decorated mansion, Youtube is hostile to canons, perfection and coherence.

Reynolds fears the ease of using Youtube. He is suspicious of the power the viewer has to choose at which point the video plays. He sees the “volume and mass,” the materialistic excess of the platform, as “quantity-over-quality” (61). His use of the term “spongiform” (63) is especially perceptive; we are faced with an image of the aesthetic world he fears as an organism, a gigantic over-decorated slime mould spreading over the landscape and overwhelming authentically creative art.

As a solution, Reynolds longs for asceticism and limits; he praises boredom as the origin of creativity, necessitating it as rebellion. He fears excessive references draining the vitality from music (75).

AI content has intensified the situation Reynolds laments. Reducing the effort needed to create content, increasing the amount of content, and multiplying old videos through AI-generated variants, the landscape is becoming even more complex and directionless. AI art can be seen as the natural continuation of the processes which have made it easier to create and consume creative media.

Terms such as “spongiform” (63) and the name “Artificial Intelligence” itself suggest that AI has a lifelike, almost organic quality. While it lacks the essential features of biological life, its ability to generate content and spread over digital space is reminiscent of mould or bacterial infection. Not only do databases like Youtube act as embodiments of excess and lack of restraint, they actually grow, spitting out AI-generated variants of the content they contain.

The original song, AI variants, and AI versions of different songs. The disorganized proliferation of variants is characteristic of the post-AI social media landscape. From a Youtube recommendations sidebar.

Revolutionary Aesthetics

Reynolds is correct in his view that AI art is hostile to ‘originality’ and ‘innovation’. It is a distinct medium with its own aesthetic values. In his article “Chance Operations,” Baillehache analyzes 20th century surrealist and futurist writing and its relation to “electronic poetry,” a 21st century precursor to today’s AI content. These movements made use of unconscious, probability-based procedures to generate content that avoided expressing their personal creative intent. For the surrealists, this was combined with the desire to access unconscious desires; “electronic poetry” was instead built around audience participation or an attempt to question the unique nature of human identity (Baillehache).

“Electronic poetry” was constructed using computer control over limited points of variance (Baillehache), unlike the unrestrained AI technology that has recently become available. Surrealist sentences such as “the new-born kitties rotate,” which Baillehache has translated into English from Breton and Soupault’s writing, form what he sees as a parallel with the randomly-constructed sentences of Wylde’s Storyland. Baillehache argues that the result of these poetic procedures decentres specific meanings and destabilizes hierarchies of quality by empowering audience understandings. He uses the example of Russian Futurist ZAUM language, which consisted of invented words (for example, those found in Aleksej Kručenyh’s poem “Dyr bul schyl”) whose meanings were left unclear.

Interpreting AI art in the context of its modernist precedents allows us to see it ‘on its own terms’ rather than expecting it to conform to traditional aesthetic principles. Rather than privileging emotion or self-expression, these movements suppressed the artists’ creative intent in order to access other possibilities. Instead of just a failed attempt to be art as made by humans, AI art can be understood as the latest in a long line of projects that deliberately limit creative control in order to explore alternative voices, such as the unconscious mind (Baillehache.)

Stylistic Comparison

Both human-centric aesthetics, as exemplified by Reynolds, and dehumanized aesthetics are valuable. AI content cannot replace conventional art. However, it is important that it is included in the category ‘art’, equally with human creations.

Firstly, there is not a clear separation between ‘AI art’ and ‘Human art.’ Artists have been using chance-based practices long before AI technology was created. Baillehache attributes such practices to the Dadaists, and to a lesser degree the Surrealists and Russian Futurists; he also records the existence of pre-AI computer generation technology. Criticisms that AI art fails to “express ideas” (Clarke) are applicable to avante-garde practices as well. ZAUM, for example, attached no meaning to its words and was intended to be interpreted in different ways based on the background of its readers (Baillehache.) Opposition to AI art could devalue intermediate practices by forcing them into one or the other category, discouraging experimentation.

Secondly, the existence of ‘Artificial Intelligence’ in unregulated online spaces creates ethical problems around rejecting AI art. It puts human creators in the position of having to suppress and dominate the creative field by eliminating suspicious works, a position similar to a pest exterminator’s or law enforcement officer’s. This attitude is detrimental to artistic practice because it forces artists into a hostile relationship with an unregulated, quasi-legal popular culture.

Thirdly, embracing an inclusive definition of art offers the potential for liberation from all standards of quality. A concrete example of how this dehumanizing process can be liberating appears in the complaint that AI content lacks a human element. The nature of this human element is ambiguous – for example “transformational creativity,” imagined as different from what an AI does in quality rather than intensity (Clarke). The implication is that there is an essentially human mind which is necessary for the creation of art. Often, this is combined with the view that AI content cannot truly communicate because it lacks intention; it is just vacuously copying real people (Clarke).

This perspective restricts art to a culturally defined standard of value – the artist Ridler pejoratively refers to AI art as “wallpaper” (Clarke). This contempt for decorative art suggests historical aesthetic prejudices, and should make us uneasy about accepting such criteria. Searching for an essential human element risks excluding fields of art that have not been prioritized as intellectually valuable. It also risks establishing a hierarchy of minds and mental states. One of the goals of the “electronic poetry” Baillehache writes of is to challenge that there is a “difference between the human mind and cybernetics” at all; privileging a human element might really be an inhuman standard which excludes ordinary human creative behaviour.

Once our aesthetics embrace this organic surge of content, we become more free.

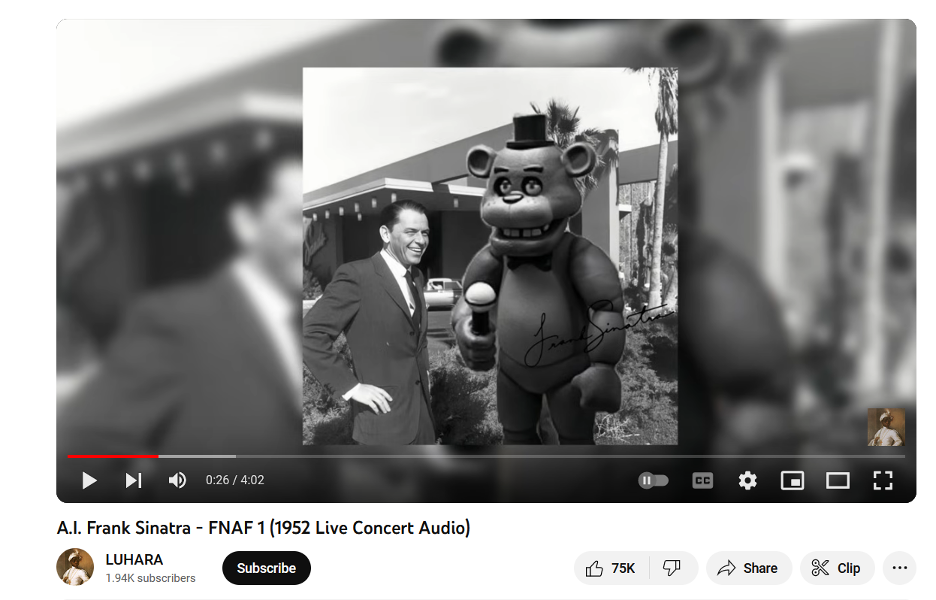

This image is probably manually edited, but accompanies an AI-generated cover song. It humourously draws attention to the combination of unlike elements enabled by AI software. From Youtube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ugjFAljBKI

Part 2: Voice and Authorship

AI’s Modernist Parallels

Metzidakis writes about the attempt by Surrealist writers to achieve “automatism” and the difficulties they faced in suppressing their artistic will. The ideal voice of surrealism is an aspect of an individual’s psychology incommunicable by language (Metzidakis 54). Success came when their works were de-individualized, failure when the “desire for authorial control” (66) emerged again.

To the Surrealists, a collective, depersonalized voice was liberating and “revolutionary,” and a private, individual voice was implicitly reactionary (Metzidakis 61). They rejected the ideology of individual creativity. While they saw themselves as accessing a deeply human unconscious state (Baillehache), the total dehumanization of the AI voice is an intensification rather than a divergence from their values.

The strategies the Surrealists and Futurists used, Baillehache argues, prefigured the aesthetics of early computer-generated writing. Their emphasis on “chance” (Baillehache) seems even more applicable to AI art than the surrealists’ actual output. The ideal of a depersonalized, universal voice is even stronger when it is electronic rather than reliant on the ambiguities of the subconscious mind.

It is not possible to see the unconscious mind of the surrealists as an essentially human attribute. Baillehache argues that the concept of “materiality” expanded surrealist theory beyond psychological explorations to a more universal level. Éluard’s statement, translated by Metzidakis, has a post-psychological, metaphysical quality: “We must erase reflections of a personality so that inspiration may burst out forever from the mirror” (64).

In light of AI’s tendency toward imitation and illusion, the term “mirror” seems perfect. AI art functions similarly to a distorted mirror, reflecting (metaphorically) shapeless patterns onto which we can project anything. As in the Russian futurist ZAUM language, where deformed phonemes give all power to the audience (Baillehache), AI content reserves nothing for authorship.

This post-psychological view allows the surrealists’ revolutionary goals to avoid datedness from, for example, too close a reliance on Freudian theory (Baillehache). It is also a natural conclusion to remove the last remnant of individuality, the subconscious mind. Total AI dehumanization does a better job of mediating between diverse human creators, because the ‘unconscious’ is not necessarily universal and may vary based on psychological features. AI art more closely approximates a universal voice because it avoids vestigial remnants of human nature.

There can be no ownership of this kind of art. By aiming for a voice which is common to all, the medium questions the ethical framework in which ideas can be privatized. In a significant passage, Metzidakis notes that surrealist practices, in the words of Myriam Boucharenc, “‘erased boundaries of intellectual property’” (64). This is a utopian goal with sociopolitical implications. “Genuine poetry erupts only once individual poets disappear,” writes Metzidakis, summarizing the opinion of Paul Éluard (64). The audience is equally empowered – it “also frees those who receive it,” Metzidakis describes Éluard as believing (64-65). The goal is “removing authors from their textual production” and the result is equality (65). This goes radically beyond the idea that AI can “democratize” (Clarke) art through ease of use. The inhuman nature that AI art is accused of having is its most attractive feature, an attack against what the surrealists would call “vanity, the poet’s mortal sin” (65).

Online spaces combine images without regard for context, creating surreal juxtapositions. This process is intensified as AI art acts without human understanding of narrative or meaning. This screenshot is a recreation of a chance combination of images that occurred when opening Kikiyama’s 2004 video game “Yume Nikki” while reading an online article. The background image is a fossilized Rhamphorhynchus from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rhamphorhynchus_munsteri.jpg

AI in Social and Economic Context

Incompatibility with the ideology of authorship drives much of the hostility to AI in the art world. Some of these complaints are legitimate responses to economic threats – for example, the fear that publishers will use AI to generate content for free, locking creators out of the industry. Some have tried to attack AI based on its failure to conform to authorship – by alleging that its ‘training’ on various images is a violation of their intellectual property rights (Clarke).

Their concerns are valid. However, preventing the creation of any work trained on artists’ images would be an inflation of the privatization of ideas to grotesque extremes. The end products of AI art do not necessarily resemble their training data, but these images would be wiped from existence regardless of the context in which they were used or published. For example, the lawsuit calls attention to the ability of AI to create imitations of artists’ bodies of work, but alleges that all images, even those which bear no such clear resemblance, “add nothing new” (Chen). It would be similar to a collage by Heartfield or Yokoo being declared the intellectual property of the various photographers whose work was cut up. AI art, however, has no human guardian to protect it from these attacks. Authorlessness is a liability as well as an aesthetic strength.

There is a deeply un-artistic quality to this attempted expansion of copyright law. It would implicate artists in an endless campaign to suppress AI content. Inevitably, peoples’ careers will be damaged by unsubstantiated claims of AI use, and the gap between professionals with access to training and amateurs without equal resources will deepen. Art cannot flourish in an environment dedicated to detecting and excluding AI content.

Regulation would have the result of making it even harder for non-professionals to use AI technology, restricting its use to powerful corporations and organizations. Both of these ‘solutions’ would increase inequality. The argument that AI can “democratize art” (Clarke) cannot be entirely rejected. Interacting with an AI cannot compare with art creation, but it could provide a space for people without the physical or financial ability to approximate what they desire to create. The popularity of AI song covers suggests that many AI users are searching for capabilities they don’t have, and ensuring AI technology is accessible could be invaluable to many peoples’ ability to participate in creative spaces.

The real threat from AI is the result of too much copyright protection – that AI content will be used by publishers and studios to replace creative workers.

If ordinary people had access to the same AI technology that corporations had, there would be little danger of the market being flooded with cheap AI content. The viability of AI products would decline if it was easier for potential customers to generate similar works by themselves. Job loss would be inhibited by the need for human creators in making successful products.

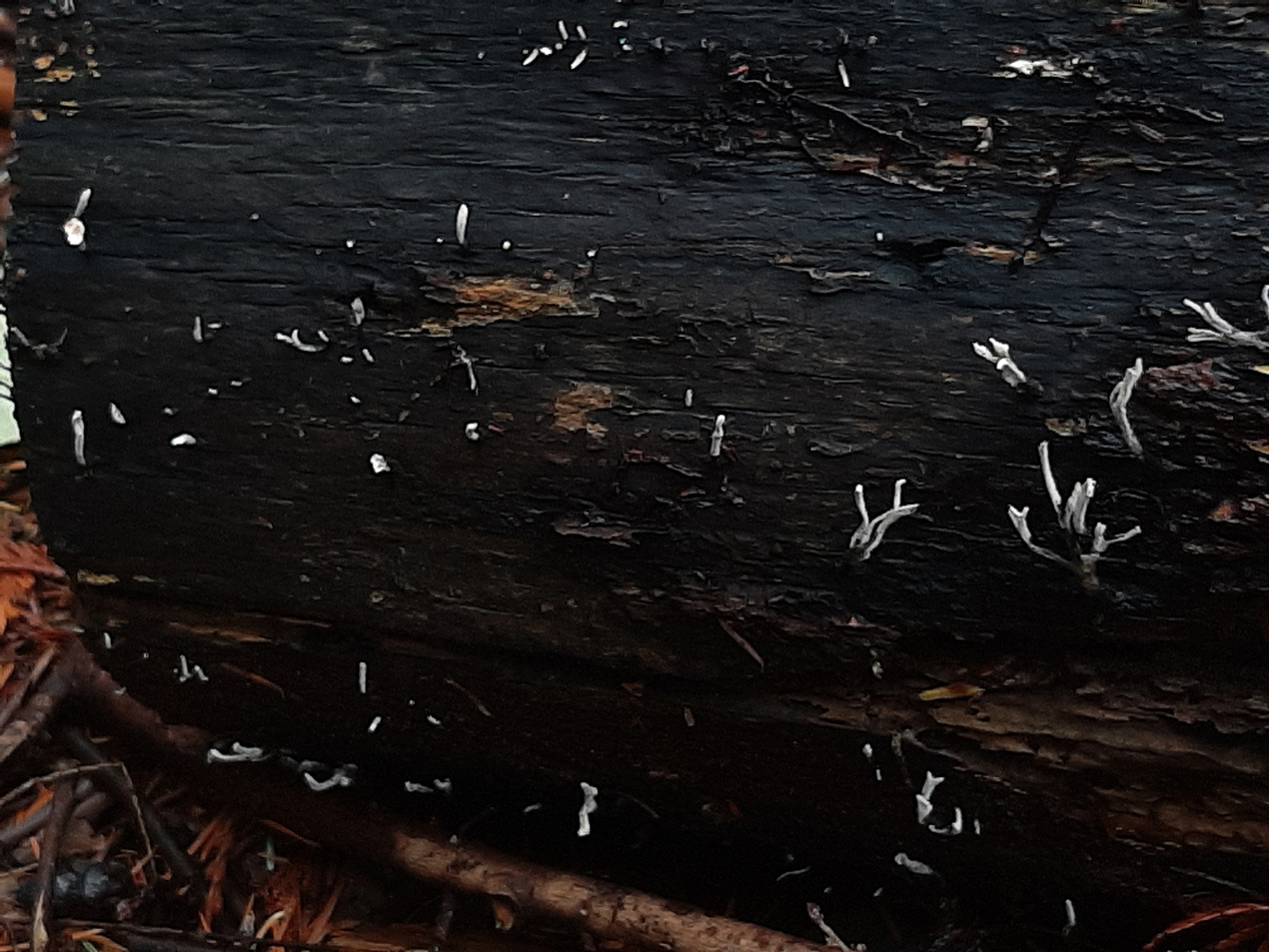

AI art, despite its inorganic qualities, spreads over digital space in a way similar to mould or fungal growth, generating content with little obvious connection to its context.

Part 3: Artist Perspectives and Social Spaces

The artist Beth Frey, who uses AI as part of her creative practice, creates photorealistic, surreal images of dreamlike – or nightmarish – beings. According to an article by Rolien Zonneveld, this series of images, which originated as traditionally painted watercolours but has grown to include AI “photographs” subjected to extensive editing by the artist, give the impression that the lifeforms they depict “actually [exist] out in the world.”

“I see my voice in it even though the AI constructed the parts,” Frey says, emphasizing the consistency between her earlier, equally surreal watercolour works (Zonneveld) and later AI images. However, she sees AI as responsible for these images’ complex interplay of reality and artificiality. “There is a photorealistic quality, but there’s also just something off that it does, and I think that’s unique to it,” she says.

Frey views the technology as, essentially, “A tool.” However, she also mentions that, “Often, there’s a surprise” when working with the technology. Frey avoids imposing too much creative control. Unlike many artists who work with AI, who, she says, “Want a very specific thing,” she allows more space for unexpected results. To begin the process of image creation, she says, “[She throws] in a bunch of really random things to confuse” the software. AI can be a powerful tool because of how, unlike a tool is expected to, it pushes back and acts unpredictably.

These works appear stronger because a degree of creative control was relinquished while making them. They have been curated and altered; however, these images’ surreal inhumanity would lose some of its power if it were not the product of inhuman computer processes. The viewer approaches these images in a different way, knowing that they are a parallel with dream imagery due to both being the product of depersonalized forces.

There may be a limit to the power of the conscious mind to create such imagery. While it’s easy to say, with hindsight, that a human artist could have created these images working alone, the pressures of our intentional creative desires might introduce biases which imperceptibly limit our work. Some of Frey’s more unsettling images might have been difficult to make intentionally, due to the degree of unease and tension they inspire. For many people, collaboration with an AI may be indispensable to bring such a work to completion.

Jesse S, who has asked for his name to be abbreviated, is an artist who has not used AI in his practice but has experimented with the technology. His view of AI technology is generally negative. He is concerned that AI users will intrude on space normally reserved for artists, for example, by appropriating the term ‘artist’ without doing the work or showing the effort normally expected. “They’re calling artists like us ‘gatekeepers’ and [claiming that we’re] making it inaccessible,” he says, criticizing the talking points of AI advocates. He also suggests the technology is built on the exploitation of artists’ intellectual property, a practice which is, he says, “Morally and legally wrong.” He elaborates, “You know, this is thievery when you’re taking someone’s art and using it to train on the machine without their consent.”

Jesse’s criticisms, though directed at AI, are also a response to the attempt to force the technology into a social role to which it is ill-suited. The struggle for career advancement and funding in the art world forces artists into disputes based on whether or not they use AI assistance, with those who work with the technology being perceived as having an unfair advantage. This is a reputation which AI advocates have been accused of intentionally cultivating, with the artist Dryhurst arguing that the threat to artists has been exaggerated, not in an attempt to rally opposition to AI technology, but for the purpose of sensational publicity (Clarke). This situation also obscures the essential value of AI art, as the technology is reduced to the status of a tool. When AI is normalized as just another medium for artists to express themselves through, it is forced to hide its own voice, its power to surprise and frustrate human creative control.

Both Frey’s and Jesse’s perspectives suggest the complexities of introducing this technology to an art world with values that emphasize individual human creativity. AI can become, in Frey’s case, a paradoxically rebellious tool, or, from Jesse’s perspective, an economic threat and competitor. Both of these approaches sideline AI’s depersonalizing potential in order to situate the technology in the art world. However, this is a source of tension as AI complicates artists’ struggles for economic resources. Rather than in the art world, AI seems least economically threatening, and at its most aesthetically unique, in the anonymous world of social media.

Returning to the “Bad Apple!!” video, the strange premise was positively received by commenters for its distance from economic niches currently filled by artists (@XemeraldXD). In addition, its premise, using lifeless renaissance pastiches as components in a surreal video, makes full use of AI’s unique potential (and saved an artist from a task that would have been both boring and unprofitable.) In the art world, coexistence could be reached if AI art was seen as a collaboration between software and human, rather than a product firmly credited to a specific human creator. However, anonymous online spaces, where there is less necessity for artists to protect their livelihoods through name recognition, might already be approaching this coexistence. These online spaces represent what the art world could be if artists were free from the pressure to compete for scarce resources in a social context that deprioritizes their work.

These apparently plain and unremarkable AI paintings undergo a surreal transformation as they imitate the “Bad Apple!” music video with their interplay between light and dark spaces. From Youtube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E58aMjthQCM

Conclusion

Attempts by artists to integrate AI into the established art world risk constricting the technology and turning it into something safe and unchallenging. The most powerful AI art is found on anonymous platforms in the form of ephemeral meme content. Once authorship is reintroduced, AI tends to lose its identity, only being valued for its efficiency at imitating conventional art – or criticized for its failure to do so.

It’s unfortunate that artists have embraced the reactionary ideology of intellectual property as a defence against AI art. When the products of AI are privatized by humans, however, it’s not surprising. Taking AI seriously and respecting its products as creative works means rejecting human claims to sole authorship. AI art is not the property of artists whose work was used in the training process, any more than a Daido Moriyama snapshot of a Shinjuku skyscraper is the property of an architect. However, the artist working with prompts is only the final perfecting step in a long process, most of which happened without them. AI art is a group effort and should be intellectual common property.

Attaching labels of authorship to AI art erases what makes it unique and reduces AI to the status of a tool. By insisting on the dehumanized nature of the medium, and empowering everyone to participate, we will make sure that humans and AI help each other grow.

The dangers of AI are not that the technology conflicts with intellectual property and authorship, but that it remains subject to a degree of ownership and control. AI platforms are owned by technology brands and access to them is limited by market economics. Instead of retreating from the potential of AI, we should go further by recognizing AI as an independent, non-human voice and removing it from private control. In addition, the products of AI should not be eligible for copyright protection. The fear that AI will cause economic damage to artists will lessen if AI art cannot be used as a substitute for mass media products.

If we expand concerns about AI’s integration with market economics into hostility towards AI art as a medium, the result will be that the art world becomes a segment of an oppressive regulatory bureaucracy. Alternatively, disconnected from technological change, the art world could slowly lose vitality until the traditional arts are fossilized, irrelevant to everyday life.

If we instead ensure that everyone can use AI technology, our creative world will become stronger, as our art transforms into something unearthly and new.

References

Baillehache, Jonathan. “Chance Operations and Randomizers in Avant-garde and Electronic Poetry: Tying Media to Language.” Textual Cultures: Texts, Contexts, Interpretation, Vol. 8, no. 1, April 2013, pp. 38-56.

Clarke, Laurie. “When AI can make art, what does that mean for creativity?” The Guardian, 12 Nov. 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/nov/12/when-ai-can-make-art-what-does-it-mean-for-creativity-dall-e-midjourney

Chen, Min. “Artists and Illustrators Are Suing Three A.I. Art Generators for Scraping and ‘Collaging’ Their Work Without Consent.” artnet news, 24. Jan. 2023, https://news.artnet.com/news/class-action-lawsuit-ai-generators-deviantart-midjourney-stable-diffusion-2246770

Enderia. “Frank Sinatra sings “It’s over, isn’t it.” Uploaded by Enderia, 10 Jul. 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iHN5zm_Rsm8

KF2015. “[Seizure Warning] Bad Apple, but Played Through AI-generated Paintings.” Uploaded by KF2015, 20 Sep. 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E58aMjthQCM

Metzidakis, Stamos. “Automatic writing and authorial egos.” Forum for Modern Language Studies, Vol. 58, no. 1, January 2022, pp. 53-70.

Reynolds, Simon. “Total Recall.” Retromania, Faber and Faber, 2011, pp. 55-85.

Zonneveld, Rolien. “Beth Frey: A fleshy world made from watercolors and AI tools.” WePresent, 25 Jan. 2023, https://wepresent.wetransfer.com/stories/beth-frey-sentient-muppet-factory

@XemeraldXD. Comment on “[Seizure Warning] Bad Apple, but Played Through AI-generated Paintings.” Uploaded by KF2015, 20 Sep. 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E58aMjthQCM