Gabriele Geremia Bucco

Gabriele Geremia Bucco (she/her) is completing her Bachelor of Arts Degree in Psychology at Capilano University, where she also earned her Communication Studies Diploma in May 2021. Gabriele was placed on the Dean’s List for four consecutive terms and placed on the Merit’s List for the Spring 2023 Term at Capilano University. Currently, she works as a Mental Health Worker for the Portland Hotel Society (PHS) serving the Downtown Eastside community. Gabriele is Brazilian and has been living in Vancouver since 2018, a city she now also calls home. Her family and friends from Brazil and Canada are her source of unlimited love and motivation to continue studying and working towards achieving her goals. Gabriele wishes to obtain a Master of Arts in Counselling Psychology in order to keep serving vulnerable communities and individuals facing mental health challenges.

My Personal Narrative

I could not have anticipated the profound impact volunteering at the crisis line at Battered Women’s Support Services (BWSS) would have on my life. At the age of eighteen after completing High School in Brazil, I decided to move to Canada alone to pursue my studies. Without my family and my friends, I immersed myself in a foreign country on the other side of the hemisphere, speaking a different language and learning how to navigate North American culture. When one comes from an outside culture and must assimilate into the dominant culture, it can be difficult to perceive the societal issues present in that new environment. I used to hold onto the belief that Canada is a beautiful country, its systems are functional, everyone is treated equally, racism in nonexistent, and the economy thrives. However, over time, my perspective changed.

My experience at the organization provoked significant effects on me, emotionally and intellectually. In addition to increasing my knowledge about gender-based violence, I gained deep understanding about ingrained societal issues prevalent in Canada, the product of the systems of oppression and colonial practices from which this country emerged. These social issues contribute to the perpetuation of gender-based violence (GBV). Contrary to the belief of many people, GBV is not merely a series of isolated incidents, rather, it is a pervasive and complex social issue deeply embedded in our society. In Metro Vancouver, there are many effective individuals and organizations, including BWSS, that provide support services for immigrant and refugee women who are fleeing abuse. The services include transitional and long-term housing, support workers, legal advocates, counsellors, and crisis line-workers. On the crisis line, I listened to the voices of many immigrant and refugee women, who are survivors of violence perpetrated by men. The insights gained from those calls stirred a form of discomfort mixed with anger, frustration, and sadness within me. Those feelings became a driving force, motivating my intertest in advocating for these survivors.

My Brazilian passport is more than just a travel document. It symbolizes the inner strength I embody as a woman and immigrant in Canada. It serves as a constant reminder to take pride in my achievements and remain grateful for my roots.

Introduction

Canada receives hundreds of thousands of newcomers every year. In 2011, immigrant women and girls represented 21.1% of Canadian female population, while projections show that in 2031 immigrant women and girls will represent 27.4% of Canada’s total female population (Hudon). A statistics review carried by Tamara Hudon indicates that the majority of immigrant and refugee women in Canada tend to live in the most populated areas, Ontario, and British Columbia (11). The report also reveals that most of these women belong to visible minority groups, such as South Asian, Chinese, Black, Filipino, Arab, Latin American, Southeast Asian, West Asian, Korean, and Japanese (9). Lastly, the report discloses that most immigrant and refugee women live with a spouse of common-law partner, that they usually take longer to integrate into the labor force compared to immigrant men, and that they have fewer local social connections compared to Canadian-born women (7). In my experience working in the crisis line, I remember immigrant and refugee survivors often expressing feelings of loneliness and vulnerability, because they had no friends or family in Canada, and the fact that they had difficulties speaking English was a barrier for them to enter the job market.

Data analyses show that immigrant and refugee women experience higher rates of violence than Canadian-born women. Over the last 15- year period leading up to 2009, there were 153 domestic violence fatalities in British Columbia (Women’s Legal Centre). Despite immigrants and refugees consisting 25% of the population in British Columbia, they accounted for 40% of these deaths (8). Immigrant and refugee women also face additional barriers when fleeing abuse and receiving support compared to Canadian-born survivors. These barriers include language obstacles, fewer support systems, financial barriers, fear of deportation, and fear of losing custody of their children. Persistent reports of misogyny, racism, and discrimination towards minority groups in Canada, that come from the police system, including the RCMP, and the criminal justice system, underscore the inherent discrimination prevalent across all levels of law enforcement. These issues are attributed to Canada’s ongoing history of settler colonialism and patriarchal ideologies. Consequently, immigrant and refugee women survivors of gender-based violence encounter heightened barriers when fleeing abuse and accessing necessary support services.

Gender-Based Violence and Intersectionality

Gender-based violence (GBV) is a term that refers to violence that is inflicted upon an individual or a group of individuals, because of their gender. It impacts cis women, trans women, and gender diverse people. GBV can manifest itself though many forms, such as physical abuse, stalking, emotional and psychological abuse, sexual violence, spiritual abuse, financial abuse, and cyberviolence (MacDougall et al.). It was documented that 850 women and girls were killed by violence in Canada during 2018-2022, being 786 cases primarily perpetrated by men (Dawson et al.). It was also reported, in 2019, that a total of 107,810 police-reported violence cases in Canada were made by domestic abuse victims, who were female in 79% of the total cases reported (Conroy). It is important to keep in mind that these figures might be higher, as many victims of gender-based violence often do not report their experiences to police or other authorities due to fear, shame, stigma, and lack of trust in the justice system.

Gender -based violence is regarded as a societal problem because it does not solely affect women on an individual level, nor does it occur in isolation. It unfolds within the broader context of the Canadian history, entwined with elements such as colonization, oppression, patriarchy, and discrimination (Mattoo). In doing so, it perpetuates gender inequality and reinforces prevailing oppressive ideologies (7). Devan Cosens, who serves as a crisis line volunteer at BWSS, works as a sexual assault response worker at Salal, and does outreach work for Surrey Women’s Centre, explained that GBV is deeply rooted in our society, and that it persists through the influence of patriarchy, misogyny, and various systems of oppression.

It is also necessary that we examine GBV through the lens of intersectionality. This involves recognizing and considering the various interconnected factors at root with this issue. Gender intersects with colonization, race, age, ability, sexual orientation, class, religion, immigration status, and other factors (MacDougall et al.). All these elements collectively shape how individuals perceive and experience gender-based violence, simultaneously influencing the types of structural support accessible to survivors (11). Therefore, it is important to recognize that a woman’s race, culture, language, and nationality will influence the lived experience of gendered violence. This is the case for immigrant and refugee women, who in their majority belong to visible minority.

Due to persistent racism and discrimination existent in the Canadian police system, many women do not report instances of sexual assault and domestic violence. The 2022 report “Colour of Violence” by MacDougall et al. scrutinizes responses from law enforcement and the Criminal Justice System, along with the intersecting experiences of survivors of color, including immigrant and refugee women. Out of the 105 respondents who participated in the research, only 14.29% felt that the police protected them (56). One respondent informed that “dealing with the police when reporting an unwanted sexual act, they did not take it seriously,” while another respondent claimed that “police don’t believe victims” (57). As it was previously mentioned that immigrant, refugee, and non-status women experience higher rates of gender-based violence than do Canadian-born women (Women’s Legal Centre), it is crucial to note that the actual rates of survivors might be even higher than the statistics show, since immigrant and refugee women often do not report instances of gendered violence because they might fear being discriminated by the police.

One of the many police vehicles used to monitor Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside/ Chinatown on a daily basis.

Barriers faced by Immigrant and Refugee Survivors

Immigrant and refugee survivors of GBV face additional difficulties when fleeing abuse and receiving support compared to Canadian-born survivors. Rosa Elena Arteaga has over 27 years of front-line experience working within the anti-violence field supporting survivors who have experienced Gender-Based Violence, and she is currently the Director of Clinical Practice and Direct Services with Battered Women’s Support Services. Arteaga explained that depending on the immigrant/refugee’s social location, race, class, gender identity, and country of origin, different barriers are created for the survivor and the support worker assisting the survivor. The most prominent obstacles faced by immigrant and refugee survivors are language and literacy barriers, limited knowledge about Canadian laws and policies, fear of deportation and fear of losing custody of their children (Tabibi & Baker). The Canadian Council for Refugees state that abusive spouses often threaten immigrant and refugee partners, who were sponsored by them, as a form of manipulation to make the woman stay in the relationship. In 2017, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) and the Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) eliminated the requirement that sponsored spouses or partners of Canadian citizens or permanents residents had to live with their spouses for at least two years to hold their status in Canada (Government of Canada). Eliminating this requirement offers relief to immigrant and refugee women trapped in abusive relationships, sparing them from enduring further harm. Unfortunately, a lack of awareness about these legal changes persists among many women, and abusive partners continue to exploit their fear of deportation as a means of manipulation.

These barriers not only add an additional layer of difficulty when survivors are trying to leave an abusive relationship and get help, but they also contribute to the perpetuation of this issue in immigrant and refugee communities. Tina Ye, who recently completed her law degree at UBC Allard School of Law and works as Legal Advocate at BWSS, explained that language and lack of access/knowledge are existing barriers that immigrant and refugee women face when they are escaping an abusive relationship and trying to find support. Ye argued that while Canada boasts itself as a multicultural utopia, survivors who cannot speak English are at great disadvantage when trying to access support in different systems. In addition, Ye stated that there is implicit prejudice from systemic actors, such as police, judges, social workers, against racialized women who speak accented or broken English. Despite Canada’s multicultural image, intrinsic prejudice and discrimination against minorities seems to be prevalent within law enforcement, judges, and social workers.

Arteaga shared the story of a survivor whose children were taken away because her husband lied by accusing her of assaulting him. She mentioned that the woman did not speak English at the time, so the police believed him, arrested her, and took the children away. Arteaga and the BWSS team worked with the domestic violence unit to demonstrate that the husband lied. They then got legal aid for the survivor and a lawyer to support her with child protection issues and family law. The woman got her children back and was able to find second stage housing because MCFD (Ministry of Children and Family Development) realized that it was the husband who was dangerous. After that, the survivor accessed BWSS’ programs including Counselling and AWARE (Advancing Women’s Awareness Regarding Employment Program). Through the employment program, the survivor could go back to school and get into college. Currently, the woman has a good job with stability and has the custody of her children.

Discrimination within Law Enforcement Institutions

As we delve into the challenges faced by immigrant and refugee women, it is crucial to recognize that bias and discrimination persist within law enforcement institutions and systems in this country. Despite Canada’s self-proclaimed status as a multicultural utopia, practical realities reveal a disconnect between the influx of immigrants and refugees and the effectiveness of services designed to protect them. MacDougall and colleagues claim that misogyny, racism, and homophobia are widely reported issues in the Canadian police system, including the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), which in turn fails to protect women from murder, violence, and abuse. Fortunately, a positive outcome emerged for the woman assisted by Arteaga and the BWSS team, resulting in the reunification with her children and stability in her personal and professional life. However, it is lamentable that such intervention was necessary, underscoring the potential avoidance of distressing outcomes had the authorities overseeing the case initially demonstrated the willingness and effort to take into consideration the woman’s perspective before reaching a consequential decision.

It becomes apparent that individuals and institutions responsible for law enforcement manifest discrimination and prejudice against minorities, including immigrant and refugee persons. In the context of laws and policies designed to support women survivors of GBV and discrimination against immigrant and refugee women, Ye argued that while the law will always strive to be neutral, the application of the law will always have intrinsic discrimination. Reflecting on the survivor’s story shared by Arteaga, it became evident that the immigrant woman, who was not able to communicate in English, encountered systemic prejudice from police officers and other authorities. Ye illustrated her argument with a frequent occurrence: “white police officers called to a domestic violence situation at a home of an immigrant family, the officer does not make a report or arrest the abuser because they think it is ‘normal’ in that culture for the husband to hit the wife. The judge in the family court denies a relocation application by the mother because she is a ‘flight risk,’ even though she needs to move with her child so the abuser cannot get to them.” Law enforcement not only frequently operates on discriminatory and biased assumptions but also ends up failing to fulfill their obligation to protect and support individuals.

Additionally, Ye revealed that the stereotypes of “hysterical mothers” or “threatening immigrants” influence the judgement of law enforcers, and that survivors frequently express feeling ignored, dismissed, or, in some cases, even held responsible for seeking to exit an abusive relationship. These discriminatory stereotypes often render racialized survivors helpless and unwilling to report abuse and seek help from the police. According to MacDougall and colleagues, this issue is not merely a symptom of a dysfunctional system. Instead, it arises directly from the establishment of police forces to enforce settler-colonialism, enslavement, capitalist accumulation, and empire.

The Criminal Code and the Criminal Justice System

Section 265 of the Criminal Code specifies that an assault charge arise when an individual induces another person to reasonably believe that intentional force will be applied to them (Government of Canada). It is important to raise the question of how often will police officers present at domestic violence or sexual assault calls recommend pressing assault charges against an individual who has threatened physical harm but has not yet acted upon those threats? The answer that echoes in our heads is that “not so often.” According to Ye, the “He-Said-She-Said” phenomenon is still very prevalent and prejudicial against the complainant in domestic violence instances, and that “abusers slip through legal punishment like water in a net.” These circumstances are even more challenging for immigrant and refugee women who might not speak English fluently and are also prone to being victims of discrimination by law enforcers involved in the case.

In 1990, the Canadian government implemented pro-charge, pro-prosecution, and pro-arrest policies in Canada, with the cooperation with local police departments, to improve the Criminal Justice System’s (CJS) response to domestic violence, meaning that the victim no longer has the responsibility to lay charges in intimate partner violence cases. A literature and policy review carried out by Ross and Ryan from Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, found that these policies are outdated and are an ineffective response to domestic violence (6). These policies create barriers for immigrant and refugee women survivors to report violence, because most times they cause unwanted Court involvement, that often leads to the involvement of the MCFD, as well as the fact that it offers limited and inadequate support services and intervention for the survivors. Additionally, the review confirmed that systemic racism, sexism, and discrimination in the Canadian Criminal Justice System is existent, including the court system” (7). Experiences of inequality and oppression, which increase the vulnerability of marginalized women, including immigrant and refugees, seem to be present in all levels of law enforcement in Canada.

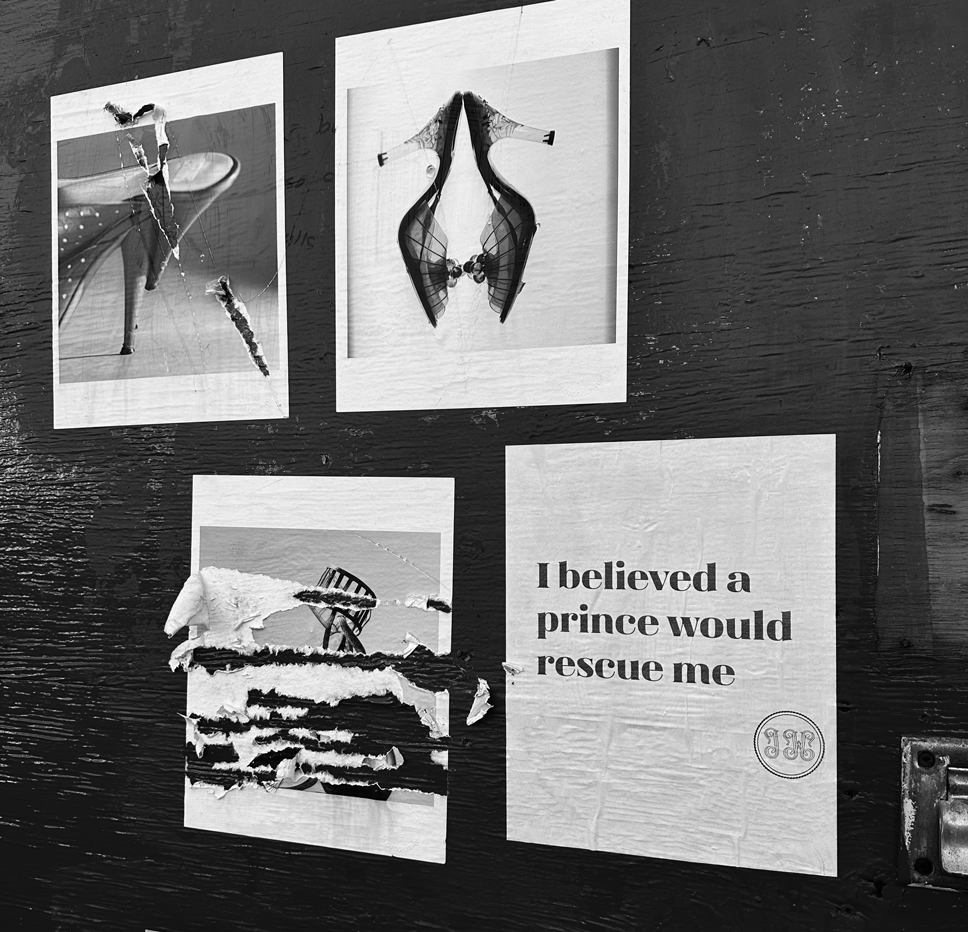

These images are located near a women’s drop-in center in Vancouver, dedicated to help street-based sex workers. Accompanied by the phrase “I thought a prince would rescue me,” they collectively symbolize the pervasive presence of gender-based violence in women’s lives.

Dismantling Oppression

Because gender-based violence is connected with colonization practices, oppression, patriarchy, misogyny, and discrimination, revolutionary changes are required. Cosens argued that it might appear overwhelming and impractical to dismantle larger systems, so the initial steps involve educating and fostering conversations to challenge internalized beliefs related to gender-based violence. According to Arteaga, the government and law enforcement systems should work from an anti-oppression, trauma informed lens, reviewing their current practices and changing them to apply the above lenses, since these systems and institutions have been founded in colonial ideas and practices. Nevertheless, the experience of gender-based violence among immigrant and refugee survivors differs from Canadian-born survivors. Not only do they encounter additional barriers when fleeing abuse such as language, fear of deportation, fear of child custody loss, and lack of greater social support, but they also endure discrimination and prejudice from law enforcers. Therefore, it is of extreme importance that the institutions in charge for enforcing the law such as the criminal justice system, and the individuals who take part in it such as the police, judges, social workers, and lawyers undergo through extensive training to understand the unique challenges and pressures faced by immigrant and refugee survivors.

Ye shared insights regarding concrete actions that should be taken by the government and law enforcement institutions to address this issue, for example, extensive and compulsory training for lawyers, especially family and immigration lawyers, judges, court workers and police on family violence; the creation of specialized courts for family matters for survivors of GBV, staffed by personnel who are attuned to the issues of GBV; youth education on GBV that focuses on dismantling patriarchal values and offers critical analysis on root causes of this problem; and lastly, prioritizing public funding for housing for survivors of GBV, making available programs like counselling, legal advocacy, and employment, where survivors can be safe and plan for the next steps. In addition to these actions, The Women’s Legal Centre suggests that it must be ensured that language interpreters assisting immigrant and refugee women in criminal justice cases are also trained on the nature and dynamics of gender-based violence, as well as the impacts of this violence for immigrant and refugee survivors (215).

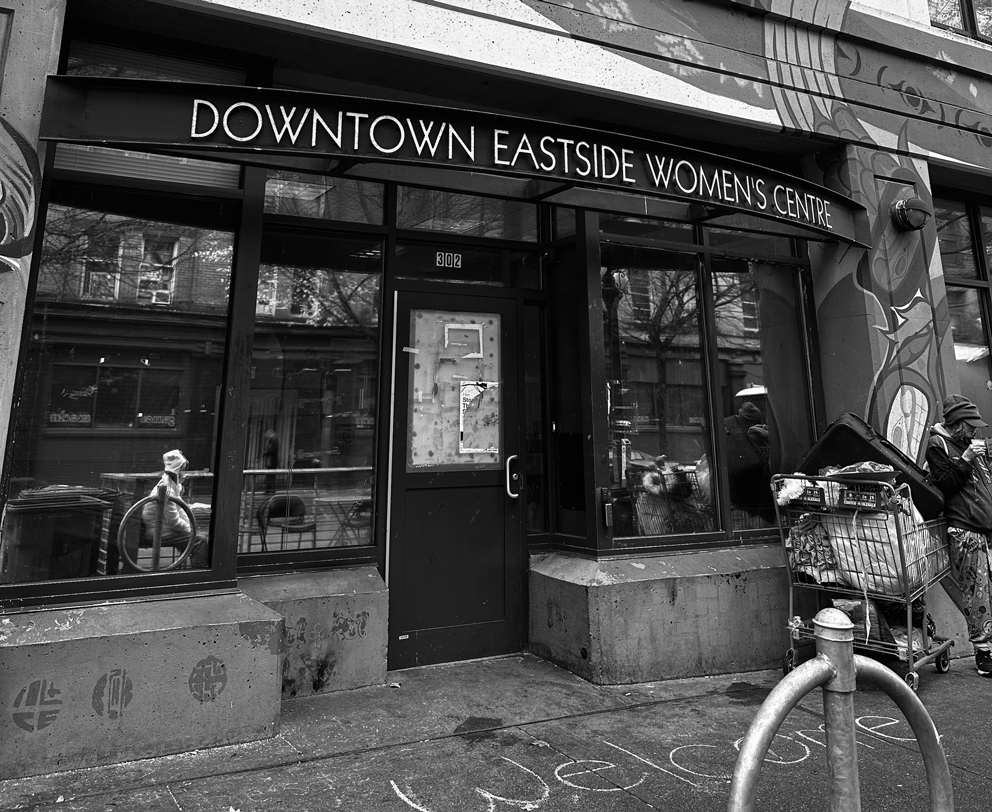

The Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside Women’s Centre provides a safe and non-judgmental space for all women in Downtown Eastside. They provide basic needs services, programs, specialized support, and emergency shelter services. The Center offers educational activities to the general public and works towards constructive social change.

Conclusion

While the laws in this country aim to be neutral, the actual implementation of these laws inevitably includes discrimination by the individuals and systems responsible for their enforcement. The narrative and instances presented in this article, coupled with interviews featuring front-line workers Arteaga, Ye, and Cosens enhance our comprehension of the challenges faced by immigrant and refugee women survivors of gender-based violence. The barriers they encounter when interacting with the police, judges, lawyers, and other law enforcement institutions show us how the inherent systemic racism and discrimination within these systems contribute to the continued perpetuation of the violence experienced by immigrant and refugee survivors. It is crucial that all individuals within law enforcement systems be educated about the issues of gender-based violence to dismantle patriarchal values and oppressive ideologies. Finally, it is crucial to conduct a thorough analysis into the deeply rooted racism and discrimination that exists at every level of the criminal justice system and how they affect minority communities in Canada. This is essential for enhancing the support and assistance offered to immigrant and refugee survivors of gender-based violence.

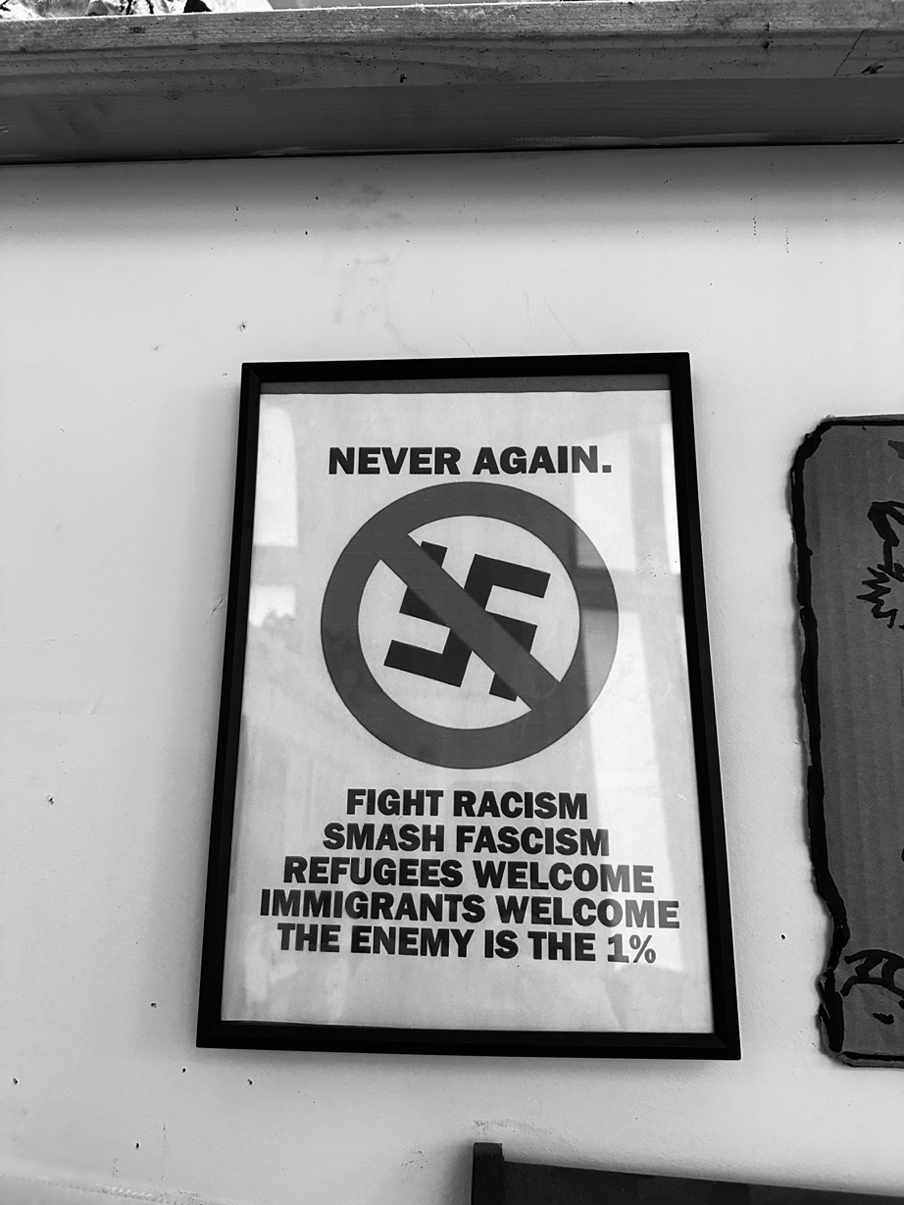

Refugees Welcome. Immigrants Welcome. I found this visual inside a safe injection site in Vancouver.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Devan Cosens, Tina Ye, and Rosa Elena Arteaga for generously sharing their knowledge with me and for the work they do to support survivors of gender-based violence. I also extend my heartfelt appreciation to Battered Women’s Support Services for their dedication to eliminating violence, advocating for women and girls, and serving on the front lines since 1979.

References

Canadian Council for Refugees. “How immigration status can affect women in situations of violence or abuse.” Canadian Council for Refugees, https://ccrweb.ca/en/how-immigration-status-can-affect-women-situations-violence. Accessed 5 Dec 2023.

Conroy, Shana. “Family Violence in Canada: A Statistical Profile, 2019.” Government of Canada, Statistics Canada, 2 Mar. 2021, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2021001/article/00001-eng.htm.

Dawson, Myrna, et al. “Call It Feminicide: Understanding Sex/Gender- Related Killings of Women and Girls in Canada, 2018-2022.” CFOJA, 2022, https://femicideincanada.ca/callitfemicide2018-2022.pdf.

Government of Canada. “Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada and Women, Peace and Security.” Government of Canada, 2022. https://www.international.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/women-peace-security-femmes-paix-securite/2020-2021-progress-reports-rapports-etapes-ircc.aspx?lang=eng.

Government of Canada, “Section 265- Assault.” Justice Laws Website, 10 Nov. 2023, https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-46/section-265.html.

Hudon, Tamara. “Immigrant Women.” Statistics Canada, 21 Oct. 2015, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-503-x/2015001/article/14217-eng.htm.

MacDougall, Angela Marie, et al. “Colour of Violence: Race, Gender & Anti-Violence Services.” BWSS, 2022, https://www.bwss.org/colour-of-violence/.

Mattoo, Deepa. “Race, Gendered Violence, and the Rights of Women with Precarious Immigration Status.” Schlifer Clinic, 2017, https://schliferclinic.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Race-Gendered-Violence-and-the-Rights-of-Women-with-Precarious-Immgration-Status.pdf.

Ross, Nancy, and Cary Ryan. “A Review of Pro-Arrest, Pro-Charge and Pro-Prosecution Policies: Redefining Responses to Domestic Violence.” Dalhousie University, 2021, https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/80242/2021%20A%20Review%20of%20Pro-Arrest%20Pro-Charge%20and%20Prosecution%20Policies.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Tabibi, Jassamine, and Linda Baker. “Exploring the Intersections: Immigrant and Refugee Women Fleeing Violence and Experiencing Homelessness in Canada.” Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women and Children, 2017, https://gbvlearningnetwork.ca/our-work/reports/report_17_1.html.

Women’s Legal Centre. “Immigrant Women’s Project: Safety of Immigrant, Refugee, and Non-Status Women.” Women’s Legal Centre, 2020, https://womenslegalcentre.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/module-1-safety-of-immigrant-women.pdf.

Individual interviews were conducted with Devan Cosens, Rosa Elena Arteaga, and Tina Ye.