Garima Grover

Garima Grover (she/her) is completing her Bachelor of Science in Biomedical Sciences at Capilano University. Throughout her studies, she has developed a strong foundation in anatomy, physiology, and human biology, with a particular interest in the relationship between oral health and overall well-being. Garima has volunteered as a chairside dental assistant at Capilano Mall Dental Center, where she gained valuable clinical experience and witnessed firsthand how compassionate dental care can transform lives. Originally inspired by her own dental journey, Garima is passionate about increasing access to equitable oral healthcare. She plans to pursue dental school and hopes to focus on serving underserved populations while advocating for patient-centered, inclusive care.

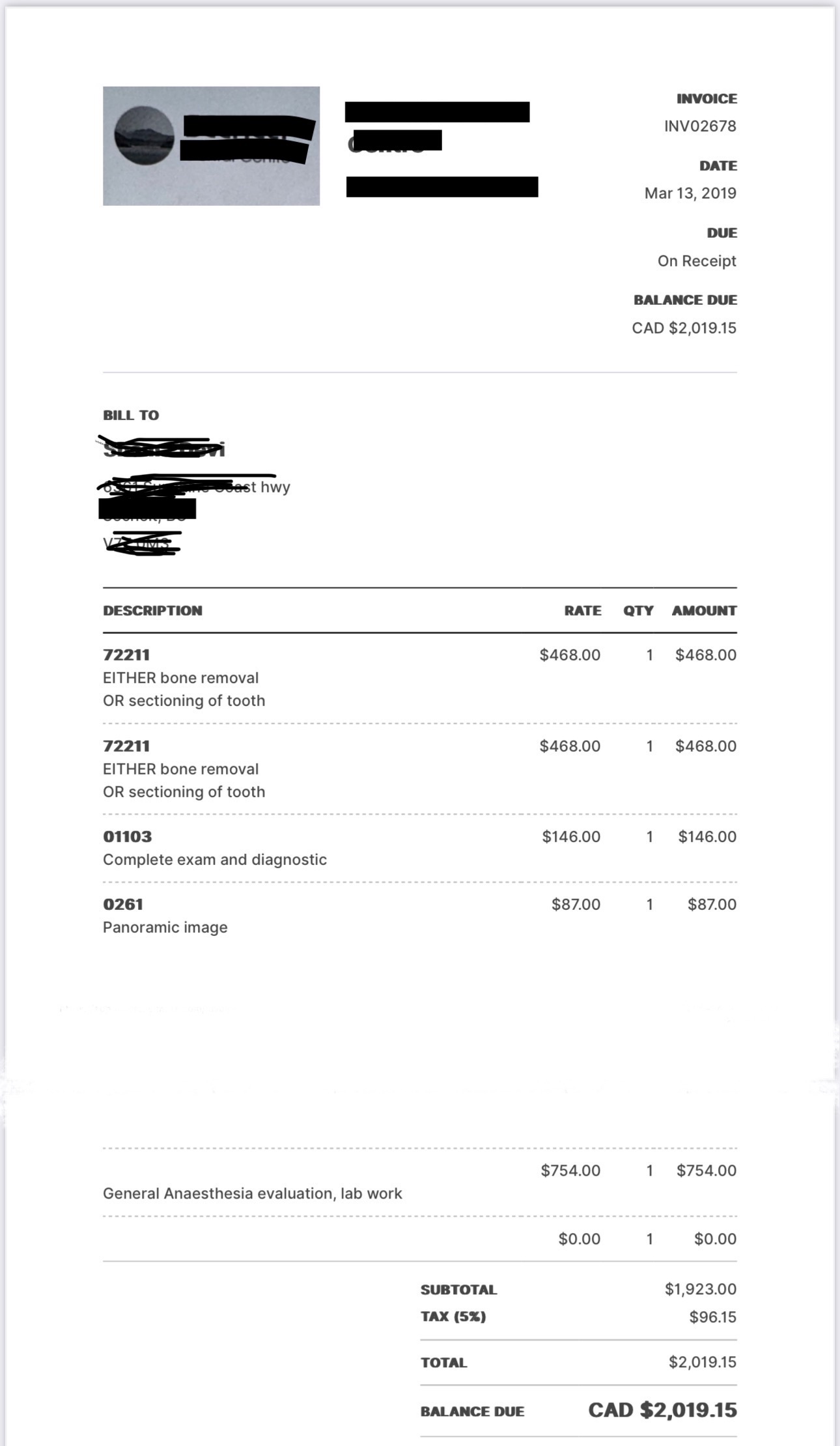

It started with discomfort. My forty-nine-year-old aunt, a single parent, experienced persistent jaw pain over several months. At the dentist, she learned that she needed complex tooth extraction procedures amounting to $4,000, which she would have to finance herself. She hesitated. The amount of money required proved challenging because she already managed household expenses for rent, food, and family costs. Financial survival became more important to her than getting medical treatment, so she decided to postpone the necessary care. The constant pain transformed into a regular component of her existence. Many Canadian stories show that the situation I describe has become quite common. Many Canadian residents keep putting off dental care services because they lack the funds required.

The Canadian universal healthcare system provides publicly funded care to all citizens, but does not include dental care, which stands as an exclusive service outside of the national framework. This exclusion has established an unsafe hierarchy, separating oral healthcare treatment from a fundamental human rights perspective. Millions of Canadian residents endure deteriorating health effects because they receive no treatment for their dental conditions, particularly affecting vulnerable populations (Canadian Dental Association). This piece investigates how public dental care reached a constitutional crisis. It examines who experiences these problems and the healthcare policies that have failed them. It also discusses community-driven solutions, such as the House of Teeth. The present dental care accessibility situation in Canada emerged from past decisions, while current public health arguments and unequal access by province continue to shape the condition of dental access.

The lack of healthcare system produces tangible personal and financial effects on individuals. Oral pain causes difficulties in concentration and job performance, as well as challenges in caring for children. People who lose their teeth experience a combination of reduced self-image, diminished job prospects, and emotional wellbeing degradation. Heavy infections from the mouth can lead to dangerous conditions and even death. The isolation of dental care from other health policies creates a situation where important patient needs become secondary matters. This exclusion has a dual impact beyond monetary considerations because it suggests that dental pain holds less significant worth compared to other types of suffering.

An empty dental chair, photographed in April 2025. Its stillness speaks to a system where care exists but remains inaccessible for those without insurance.

A Neglected History: The History of Dental Care in Canada

Knowledge about the present dental care system in Canada requires examination of historical data. Before the 1960s, all health care services in Canada operated on a private basis. The Medical Care Act of 1966 and the Canada Health Act of 1984 established the framework for universal healthcare coverage throughout the country. Both healthcare policies omitted dental healthcare services. The reasoning? The medical community in that period misidentified oral diseases as separate from overall health, which produced enduring negative results (Journal of the Canadian Dental Association 152).

Individuals who lacked both dental coverage and financial capability needed to use private dental services since public care options remained minimal during that period. During the 1970s governments launched restricted public dental services which operated for only a brief duration while receiving little funding support and varying between different provinces (National Library of Medicine, 2021). Dental care remained outside the domain of healthcare initiatives because medical and policy experts failed to view oral health as fundamental for surviving at that time (National Library of Medicine, 2021).

Water fluoridation, which Canadian cities started adding to drinking water supplies in the middle of the 20th century, proves effective for decreasing dental decay, particularly among people who earn less (Public Health Agency of Canada 2023). However, its implementation is patchy. Calgary turned off its water fluoride supply in 2011 but brought it back in 2021 because its residents noticed rising dental troubles among their young population (Canadian Dental Association). Most people oppose the implementation of broad water fluoridation programs because of resistance from communities, inaccurate information spread among citizens, and economic issues confronting municipalities (Canadian Dental Association).

Who Gets Left Behind? Barriers to Dental Access

The population experiencing the greatest difficulty with dental care in Canada belongs to marginalized groups. Every year, lower-income populations, those who are homeless, newcomers, Indigenous populations, and disabled Canadians experience the biggest barriers to dental care access (Canadian Dental Association).

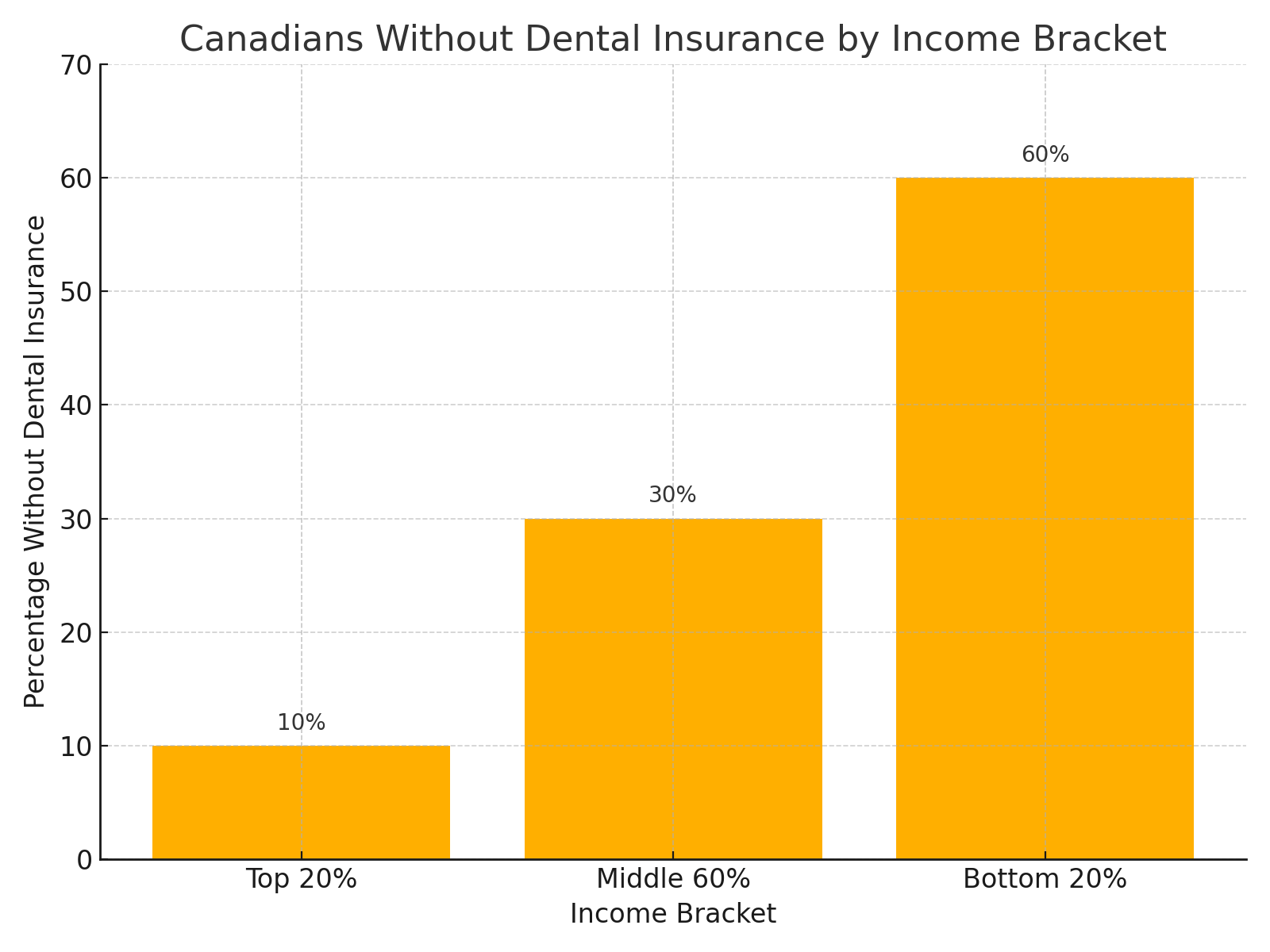

Approximately one-third of all Canadians do not have access to dental insurance benefits. Among those in the lowest income bracket, this figure rises to over 60%. Research published in PLOS ONE showed that expense-related dental care postponement or omission affected 59.1% of people who did not have dental insurance (PLOS ONE). The insurance coverage provided to some individuals proves inadequate, since essential dental operations are barred from benefits, and annual maximum payments fall significantly short of medical costs (National Library of Medicine).

Multiple serious side effects extend beyond superficial results. Various systemic diseases— including cardiovascular conditions, diabetes, and respiratory problems—along with mental health difficulties, are directly associated with poor oral health status. Oral infections maintain direct impacts on health results, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada (Public Health Agency of Canada 2023). Despite this, oral health remains an insufficient priority within public health planning processes.

Healthcare in Vancouver Downtown Eastside stands as a clear demonstration of universal health care differences through its services and shows how broader access issues become concentrated in particular neighborhoods. Multiple issues involving drug addiction combined with poverty and trauma create severe oral health problems while cutting off the residents from acceptable dental healthcare. Dental clinics remain inaccessible for most people since their prices are high and formal atmosphere makes many individuals feel unwelcome particularly those with housing challenges or mental health conditions (Canadian Human Rights Commission). People who have medical coverage with their partners continue to experience troubles with healthcare services. Emergency visits represent the one allowable benefit under provincial coverage programs that prohibit all nonsurgical services. A low-income patient can receive emergency tooth extractions but will not get regular dental cleaning that could prevent such issues (National Library of Medicine).

Most healthcare facilities keep long waiting times for their patients and providers accessible to few areas across the country including distant rural regions due to transportation challenges. The residents in northern communities have to go great distances by both air and road to find a dental provider in their area. Medical conditions of patients deteriorate alongside rising healthcare costs from extended delay periods (Statistics Canada). Living within Indigenous reserves means going through federal governmental bureaucracy that produces extended waiting times and few accessible service choices (Canadian Human Rights Commission).

Inside House of Teeth, a trauma-informed clinic in Hastings Vancouver. The calming environment was created to welcome patients who’ve avoided care due to fear, stigma, or financial strain.

People who have disabilities must overcome multiple challenges in their healthcare journey. Certain clinics operate without suitable machinery for properly treating patients with complex medical conditions. The combination of stigma from providers and society makes people reluctant to get help. According to the Canadian Human Rights Commission, the current dental system structure maintains discriminatory practices which violate the rights of vulnerable populations (Canadian Human Rights Commission).

A Fractured System: Canada’s Dental Care Policies

The government recognizes the dental catastrophe, though its plan to resolve it moves at a slow and inconsistent pace. The most important announcement came in 2022, when the Liberal government under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, in cooperation with the New Democratic Party, introduced the Canadian Dental Care Plan (CDCP). This initiative was part of a supply-and confidence agreement aimed at expanding access to care for uninsured Canadians earning under $90,000 annually (Government of Canada 2024). The program began implementation in 2024 by offering dental coverage to children under the age of twelve, with plans for future expansion.

Critics contend that the Canadian Dental Care Plan faces two major drawbacks while being launched too slowly. Several Canadians continue without health insurance coverage, while provincial health services have implemented the policy at different speeds. Remote sections of Canada still experience both inadequate health plan coverage and insufficient access to dental service providers, according to the Canadian Dental Association (2023). As of early 2025, many Canadians continue to wait for meaningful access to the benefits promised under the CDCP. Some patients report that applying for CDCP involves complicated bureaucratic measures. Program advocates claim that proper outreach, along with education and program simplification, could help ensure that more Canadians know about the program and feel comfortable applying. Without those changes, many of the individuals who need the program most might never access it. These ongoing barriers suggest the CDCP could fade into disuse, despite being designed to bring transformational change (Journal of the Canadian Dental Association 154).

The expense of not addressing the situation remains steadily increasing. Dental pain drives numerous expensive visits to emergency departments throughout Canada. The Canadian Institute for Health Information reports that annually, more than 60,000 Canadian patients visit emergency departments due to preventable dental problems (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2022). Hospital facilities experience excessive pressure because patients only obtain brief treatment instead of long-term solutions.

A Compassionate Response: House of Teeth and Community-Led Solutions

Traditional institutions have failed to function properly, so various grassroots organizations stepped forward to help. The Vancouver-based organization House of Teeth, founded by Dr. Sean Sikorski emerged to serve the local community and vulnerable populations. During the interview, Dr. Sikorski explained that his practice provided care to patients who had delayed visits to the dentist for multiple years.

Through House of Teeth, Dr. Sean made it its mission to transform this reality. The clinic serves any patient requiring dental services by using a fee system that calculates costs based on individual financial ability. The organization located on East hastings works with local health initiatives to provide free health screenings, health service referrals, and outreach programs. These outreach efforts include dental assessments offered at shelters, schools, and community centers with low barriers to entry. One patient shared that it was the first dental exam they had in ten years, because the clinic’s approach felt “safe and non-judgmental” (Sikorski).

What distinguishes House of Teeth from other clinics is its distinctive trauma-informed method of operation. The staff receive training to deliver care that demonstrates respect while remaining nonjudgmental and accommodating to patients. This clinical approach results in a major impact on patients who have already experienced mistreatment by traditional medical centers. The clinic creates inviting spaces and peaceful settings to help patients cope with anxiety, particularly benefiting those who had bad experiences in dental settings (Sikorski). One patient, a 36-year-old woman who had avoided dentists for over a decade due to a traumatic experience as a child, shared that House of Teeth was the first place where she “didn’t feel judged or afraid.” She described being offered a weighted blanket and calming music during treatment and said the clinic’s approach helped her manage anxiety and regain trust in dental care (Sikorski).

Taken just steps from the heart of the Downtown Eastside. This neighborhood highlights how poverty, addiction, and stigma intersect with health outcomes—including oral health. Many residents in this area rely on outreach programs for basic dental care.

The House of Teeth organization is creating a toolkit that enables other communities to duplicate its healthcare model. The toolkit contains instructions on trauma-informed dental services, relationship development between dental centers and health organizations, and specific outreach strategies to engage patients who have not visited clinics before. Dr. Sikorski described this as “a guide built from experience, made for communities that feel forgotten” (Sikorski). Through its grassroots operations, this healthcare model demonstrates the steps healthcare should take to deliver better access, dignity, and equity to patients.

While these projects are motivating, they cannot operate as a substitute for laws and policies at the national level. These examples show human strength rather than replacing fundamental human rights. These medical facilities provide a care model that demonstrates how future policy should evolve through patient Centered approaches and flexible designs rooted in real-life insights. The nationwide expansion of this model would generate an inclusive approach toward change.

Challenges and Changes: What Needs to Change?

Quebec serves as an essential province for carrying out necessary reform. It demonstrates leading social policy capabilities, even though it trails behind other provinces in water fluoridation practices. Dental screening services launched in Quebec City and Montreal through local housing programs and mental health outreach efforts offer a model for other regions to follow (Statistics Canada).

The Canadian Dental Care Plan moves forward positively yet requires accelerated implementation, expanded coverage, and enhanced financial backing. Healthcare coverage needs to be accessible to every resident in Canada without exclusions. Additional financial support is required to properly develop rural and Indigenous communities. Better integration with provincial health organizations will help eliminate unnecessary repetition and deliver services more efficiently (Government of Canada).

Canadian health systems must create solutions to tackle fundamental social health factors such as income disparities, homelessness, and racial biases. Health inequalities run directly through dental care provision. The path to genuine change demands a complete understanding of comprehensive health. Governments should involve patients in decisions and invest in culturally sensitive, custom-fit solutions. A successful future means implementing universal dental care—where every Canadian, regardless of income, location, or age, has access to preventive and emergency dental treatment without financial burden (Journal of the Canadian Dental Association 156).

A stark income-based divide in access to dental insurance reveals that only 10% of the top income earners lack coverage, compared to a staggering 60% of Canadians in the lowest income bracket. These disparities reinforce systemic inequality, where oral health remains out of reach for those already facing financial vulnerability (Statistics Canada, 2023).

An effective solution for dental healthcare involves expanding mobile services and increasing the number of community dental clinics. Proper funding of these population-specific models enables them to serve populations that are difficult to reach. Policy initiatives must implement and grow such programs. Educational efforts combined with destigmatization of dental issues will effectively increase public pressure for systemic reform in oral healthcare access. The next stage of reform must approach both accessibility and public awareness as essential components.

The responsibility also extends to universities and dental colleges. Public health training combined with community placements in dental education creates practitioners who understand the complexity of health inequalities and can effectively address such issues. Dental schools should recruit more BIPOC students to help develop a workforce that reflects and understands Canada’s diverse population. This kind of representation matters—not just in policy meetings, but in exam rooms, clinics, and community outreach programs (Canadian Human Rights Commission).

Government policies must establish safety measures to defend the rights of individuals who perform work as independent contractors or hold unstable job positions. The lack of companies providing full employee benefit packages creates millions of uninsured individuals. Modern workers could obtain protection through portable dental plans that serve as a secure financial foundation. These plans would allow workers to carry their dental coverage with them between jobs or contracts. Targeted subsidies with denture programs should be implemented as essential support for aging individuals, because their oral health frequently receives limited attention (Journal of the Canadian Dental Association 157).

Conclusion

She received dental surgery only after obtaining financing, which she continues to pay back. There is no more physical discomfort, but the financial weight continues to affect her life. Her story is far from unique. Thousands of Canadians throughout the country face this double challenge because they must choose between maintaining health and securing their basic existence. Oral health corresponds to more than superficial appearance. The cause of dignity matches with equity and basic human rights.

The good news about change rests in its possibility for achievement. The Canadian Dental Care Plan represents the first step toward better dental services. House of Teeth demonstrates the positive impact of service-driven healthcare instead of profit-driven healthcare. Canada can only achieve its healthcare ideals by ending the dental disparities that exist in its population. The solution demands financial support, proper laws, widespread education, and partnership with community groups. A person’s health starts in the mouth because oral wellness directly affects overall body wellness. Hearing the story of my aunt demonstrates that such situations need to end permanently.

This treatment estimate shows the cost of removing impacted teeth, totaling $2019.15—with no insurance coverage. For many Canadians, bills like this mean delaying care, taking on debt, or living in chronic pain. My aunt’s story began in a similar form.

The ideals of universal healthcare should not stand beside occasions where people endure pain in order to express their smiles in a nation that boasts both wealth and compassion. A genuine healthcare system only exists when it shows compassionate treatment to its citizens without considering their financial level, geographical location, or individual situation. The existing conditions allow Canada to emerge as a global leader. A small number of high-income countries continue to prevent dental coverage from reaching their citizens under universal healthcare. The complete integration of dental coverage by Canada will establish an international leadership position through which other nations can develop their healthcare strategies.

Public health in Canada faces a pivotal moment in its history, where the country must bridge gaps between populations, tackle inequalities, and choose to protect its citizens’ health. The existing situation demands moral action. The principles of human rights and fairness in this nation demand that residents avoid tooth decay and painful abscesses. We must consider what society should become in the future because that concerns our present-day choices. Should we accept unnecessary suffering as a natural part of life, or should we act on the obligation to provide healthcare to everyone?

The time has come for Canada to eliminate its institutionalized healthcare abandonment rooted in past policies. The importance of oral healthcare for patients should match other fundamental medical requirements. With the proper tools, we can eliminate the deep injustice that affects our society by treating it at its foundation. The human mouth functions as an inseparable part of the body, and dental treatment maintains essential connections with public health practices. They are one and the same. We should maintain complete openness through our policies, our systems, and our hearts to guarantee all Canadians experience pain-free health without fear. This is not just about teeth. It’s about equity. It’s about justice. Someone looking ahead should recognize our future requires everyone to succeed beginning with something basic and essential that represents humanity: smiling.

References

Canadian Dental Association. The Impact of Inaccessible Dental Care on Overall Health. 2023, www.cda-adc.ca/en/about/media_room/news/2023/dentalaccess. Accessed 28 Mar. 2025.

Canadian Human Rights Commission. Disability and Access to Health Services in Canada.

Government of Canada, 2022, www.chrc–ccdp.gc.ca. Accessed 28 Mar. 2025.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Emergency Department Visits for Dental Conditions.

2022, www.cihi.ca. Accessed 28 Mar. 2025.

Government of Canada. Canadian Dental Care Plan (CDCP): Overview. 2024, www.canada.ca/en/health–canada. Accessed 28 Mar. 2025.

Journal of the Canadian Dental Association. “Policy Solutions for Dental Care Accessibility.” JCDA, vol. 88, no. 4, 2022, pp. 150–157.

National Library of Medicine. “Financial Barriers to Dental Care in Canada: A Review.” National Library of Medicine, 2021, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/NLM2021. Accessed 28 Mar. 2025.

PLOS ONE. “Cost Barriers to Dental Care in Canada: A National Survey.” PLOS ONE, vol. 18, no. 7, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0289345.

Public Health Agency of Canada. Oral Health and Its Link to Systemic Disease. 2023, www.canada.ca/en/public–health. Accessed 28 Mar. 2025.

Sikorski, Sean. Personal Interview. 15 Mar. 2025.

Statistics Canada. Access to Dental Care and Insurance Coverage by Income Level. Government of Canada, 2023, www.statcan.gc.ca. Accessed 28 Mar. 2025.