Zoë Macdonald

Zoë Macdonald is a student in her final year of Interdisciplinary Studies at Capilano University. She previously spent two years studying Anthropology at the University of Victoria. At both institutions, Zoë received high marks and has continuously achieved standing on the Dean’s list. Her passion lies in the field of education, with a specific interest in literacy. In the future, she plans to enter a graduate program in the field of information and library sciences, with the eventual goal of becoming a librarian.

Since the public release of ChatGPT in 2022, generative AI has spread across countless digital spaces. It is reshaping digital information landscapes by altering how individuals engage with reading, writing, and research. Across multiple platforms and content creation spaces, AI has and continues to be introduced, often without regulations or rules to hold it accountable for providing correct and factual information. With universities and post-secondary institutions being so closely linked with research, information and education, it is important to ensure AI literacy skills are developed, implemented and maintained in student populations. The popularity and usage of these generative platforms are growing at a very rapid pace. This increase in AI use is not slowing down anytime soon and has the potential to be a desired skill in the future. It is important to both understand the harms and benefits GenAI can bring and the literacy skills that need to be developed to continue to protect information and critical thinking skills while introducing new platforms that have the potential to benefit education experiences.

Definitions

When learning new technologies, we must also learn new vocabulary and the definitions behind them. Students need to be equipped with the proper terms and understanding of AI-specific jargon so that they can understand and properly identify different aspects of generated text (Ciampa et al. 2023). The terms below have been chosen because they are the most commonly used in discussions surrounding generative AI, and because they are foundational vocabulary words needed when building AI Literacy skills.

Generative AI

Generative AI, also sometimes referred to as ‘Gen AI’, is a common type of artificial intelligence technology that is used to generate and synthesize content. This content can be in the form of text, photo or video. GenAI is a specific type of Artificial Intelligence, although for the sake of simplicity, in this paper, I will refer to generative AI as ‘AI.’

Chat GPT

Chat GPT is one of the most common and popularly used generative AI platforms founded by the company OpenAI (More and Bothe, 2024). A user can give ChatGPT prompts and it then generates content based off of the prompt.

This is the Chatgpt website when it is waiting for a user to enter a prompt. It is asking “What can I help with?” as if it is a first-person thinker.

Prompt

A prompt is what is input by the user into an AI program to elicit the generation of content. Prompts can take many different forms, such as questions, instructions or descriptions. For example, by typing a prompt into it, such as ‘write a 500-word essay about Urban Sprawl’, users will cue the generative AI to generate a 500-word essay. Users can write and enter prompts in the ‘ask anything’ space as pictured above.

LLM

Large language models, or what is more commonly referred to as LLMS, are what generative AI is trained on. These are the articles, information and text that are fed into AI for them to learn.

Hallucination

A hallucination is when generative AI creates text using information that is not true; it makes up the answer or spits out generated text that is not correct.

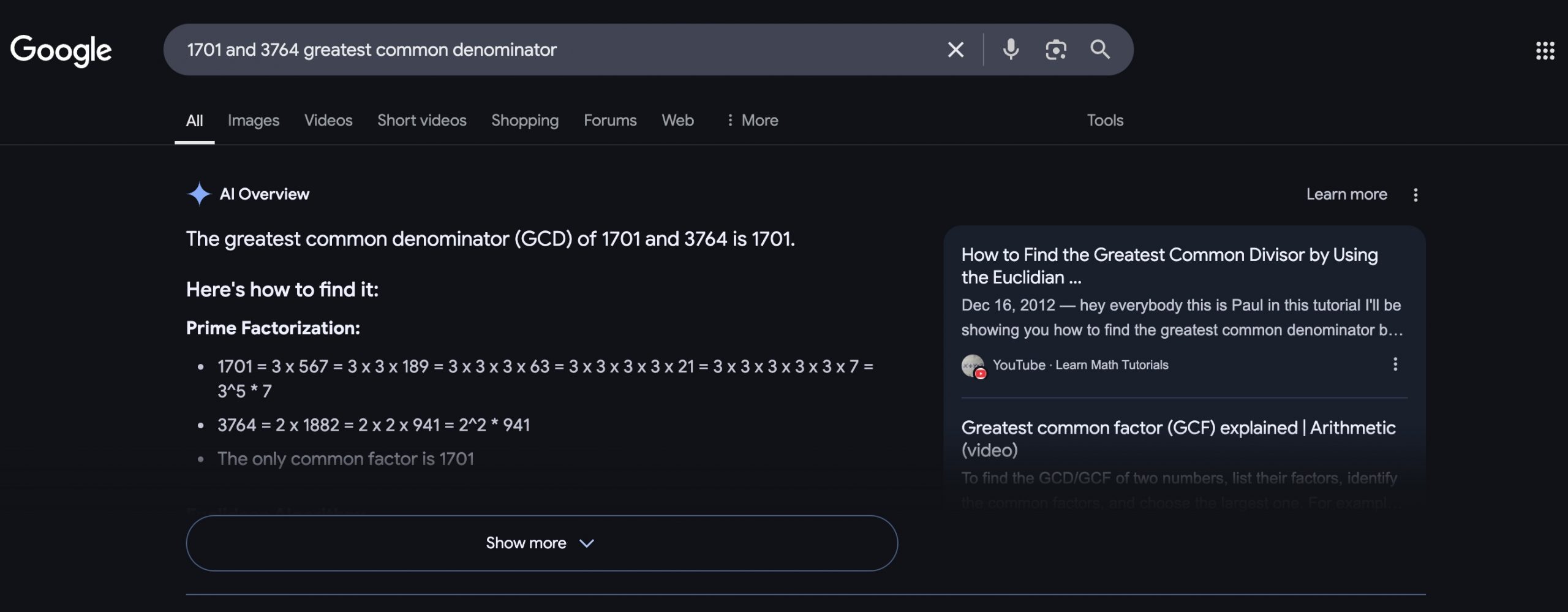

A Google search result showing the AI Overview feature. It breaks down the problem and shows you how it get the answer! The Overview looks official and even explains itself, unfortunately, it is not correct. The answer is 1.

Black Box

Black box is a term that refers to what cannot be accessed about the creation of the generated content. As a user, you do not know what literature and information was used to generate the output you receive, you are unable to access the source material or understand where the content you received has been created. This is important because the writing may seem very factual and correct, but you have no access to the original content or understanding of biases the LLM may be holding and are unable to find them out because, as an individual, you cannot access all of the information contained in an LLM (Wan 2024).

Timeline of Generative AI

Generative AI became widely available and easily accessible to the public with the release of Chatgpt-3 in 2022. Created by the larger tech corporation OpenAI, ChatGPT was trained using large foundational LLMS and is continuously trained on new text and information fed to it through its users. Within the first five days of its release, ChatGPT had over one million users (Marr, 2023). GPT-3’s release in 2022 marked the first time that the public was able to directly interact with AI in this way; GPT-1 and 2 had not been uploaded online. By the end of its first two months online, Open AI’s ChatGPT had over 5 million daily users (Ciampa et al. 2023). Later in 2022, Google and Facebook also released their own AI platforms, Gemini and Meta, and quickly started integrating them into their existing products and software platforms (Tzirides et al. 2024).

In the last three years since its public debut, Chatgpt has continued to update and release new versions, the latest at the time of this article being GPT-4.5. AI is also being introduced into many different fields and large companies, with ChatBots replacing humans in customer service positions and generated voices and videos being used in marketing. Some social media sites such as Facebook and Tiktok are also full of fake videos generated by AI, with misinformation that is being believed by many of the consumers of that media.

Current Environment

Currently, there are several problems surrounding AI use in universities. Students are not understanding when and what AI should and can be used in academia, the decline in research and information verification skills and the lack of knowledge surrounding the parameters of AI are all contributing to the need for AI Literacy Education for Students. Because of a lack of regulation and policy at the university level, students are using AI to complete assignments for themselves without worrying about extreme repercussions (Brew et al. 2024).

With well-worded prompts, students can get AI to generate entire essays, and while the content of the essays may not be accurate, the grammar and writing are. ChatGPT can create well-structured and grammatically correct writing that often has correct information. When talking about the accuracy and nuance in the content generated by AI, Alice Everly explained that “Chatgpt can probably get a D in my class” (Personal communication, March 20, 2025). While the writing is good, AI is not able to know or understand the specific materials that you are learning from and can not create nuanced opinions and connections like an actual student can. Currently, it is also not well understood by all students that Generative AI is not a search engine or a source for information. Platforms such as Chatgpt can create well-written content, but they do not always provide true or correct information (Brew et al. 2023). It cannot give specific information or fact-check itself. What it can do is write and generate information nicely, which many students know.

If students start relying on AI to do their work for them, it may lead to “deskilling” (Berdahl, 2025), with students losing the skills to do work themselves. If you are relying on generative AI to plan all of your essays, format bibliography entries or write your discussion posts, then you will never gain the skills to do this yourself. In many of my class discussion posts this past year, people have uploaded generated content full of hallucinations. Instead of quoting the material we learned, uploaded posts are made with completely different vocabulary and mention people or concepts completely irrelevant or incorrect about the discussion materials. Sometimes, multiple students in the class will have the same hallucinated information present and completely disregard all other students’ responses in the class.

Platforms like Chatgpt can be asked to generate citations for a paper surrounding specific subjects, yet none of the references exist. Bibliographies will contain the names of real scholars in the correct fields, yet the articles referenced cannot be found. Instead of providing accurate sources, AI has hallucinated the titles of articles, and dates of publication and simply added on names of scholars associated with the field. Some students have also handed in papers with references to non-existent articles with publication dates listed years after the author had died (K. Nowak, Personal communication, March 17th, 2025). While these citations may be properly formatted, they are not listing real publications and show a clear lack of actual research from the students handing them in. This is creating a large problem for teachers, who are now spending more of their time trying to identify AI than marking actual papers (A. Everly, personal communication, March 20, 2025)

A fourth-year university student doing online research at the West Vancouver Memorial Library. Physical and digital libraries continue to hold and curate quality information and research. In the age of AI, they are integral to AI Literacy education.

When discussing why AI literacy is important, Krystyna Nowak, one of the librarians at Capilano University, explained that students, “Need to understand these limits to be able to use them as a tool”(Personal communication, March 17th, 2025). If students are not aware of the shortfalls of some of the generative AI platforms, they will continue to use them in harmful ways. How to Identify AI, what AI platforms can be used and which ones should be shied away from. These need to be continuously adapted, as generative AI is also adapting. When chatgpt first released, it was not able to search the internet, it now can draw from the internet, meaning that it has an incredible reach and can answer questions that maybe it could not have before, but it also means that it follows the general narrative of the internet and the patterns we see in our own culture and what is being put online.

Writing and Reading

AI is currently disrupting current literacy strategies, such as spell-checking, editing and reading comprehension skills (Chaudhuri & Terrones, 2025). It may be tempting for students to get AI to check their paper for grammar and spelling mistakes, but this comes at a detriment to the student. While grammar for students seemingly becomes better due to the AI fixing mistakes, the individuals using these platforms are losing grammar and spelling skills (Chaudhuri & Terrones, 2025). Students can receive immediate feedback on their writing with corrections and suggestions if they copy their work into ChatGPT, but they need to read and reflect on these suggestions for it to become a tool (Ciampa et al. 2023) As part of AI literacy, students need to learn how to create prompts that will help elicit the responses they need and to think critically to get nuanced content from AI (Tzirides et al. 2024). Having the skills to be able to write prompts that will elicit better responses that will contribute to learning and improve output will also be a skill that is translatable outside of education.

Reading comprehension and being able to identify and recognize when a text may have been generated by AI are also important. Because of the ease with which text can be generated, AI writing, images and videos are becoming more and more common online. When interacting with any media, students need to be on the lookout for AI indicators, such as repetitive vocabulary and a lack of nuance or detail on a topic.

A word cloud generated on www.freewordcloudgenerator.com using the key terms and vocabulary list brainstormed for this paper the prompts for the word cloud. This shows how AI could be used as a tool to demonstrate learning.

Research Abilities

Nowak recalls hearing a quote on a podcast: “When I am an expert in something, Chatgpt is right 5% of the time; when I am not an expert on something, Chatgpt is right 95% of the time,” which perfectly explains one of the pitfalls of relying on AI as a source for information (Personal communication, March 17th, 2025). When we do not know what the correct answer is, it is easy to believe what AI tells us is correct. There is no fact-checking or system in place to make sure that Chatgpt, or Google’s AI overview, is using correct and updated information. This is extremely dangerous for people who do not realize the difference between an information search engine, such as Google, or databases like EBSCO, because they may be taking all of the content AI gives them as fact. That is why information verification and critical thinking are skills that need to be continuously fostered (Sanchez et al. 2024).

In an AI literacy Framework, students need to understand that AI is a starting point for research, not a destination. Generating lists of key terms related to a topic is something ChatGPT is more than capable of. Students then need to take these terms and use them in proper search engines and databases. Learning that if AI gives you the name of an article or the name of a person, it is up to you as the user to verify that outside of the AI platform. This verification step is important, as even if AI looks credible, it does not hold any obligations to be that way.

A classroom of upper-year students at Capilano University. Some will enter into careers and start jobs in the fall, while others will continue in academia and pursue graduate studies. In both of these situations, students should leave University with the AI literacy skills to lead them successfully down their chosen pathway.

These platforms are meant to generate content, not provide information. A search engine, such as Google, will provide you with links to gain access to the information. Databases such as EBSCO provide articles that have gone through fact-checking and scholarly review processes. A platform like Chatgpt will generate text that reflects the prompt, this is different from providing the actual answer to a question posed. Chatgpt does not provide links, and as a user, you have no way of verifying if it is correct or not unless you do follow-up research.

The Google AI Overview feature is also consistently unreliable and can be turned off. Even students who may have good intentions will be subject to false answers sometimes because it is unavoidable to switch off that tool. Reading all the links that Google provides and understanding the content behind these generated texts are extremely important, and that needs to be communicated to students.

Bias

Students in universities need to be taught about how LLMS influence the output of generative content. If the information contained in the LLM has biases or a lack of a certain perspective, that will be reflected in the output generatChatgpt-3PT-3 was studied by researchers and found to contain biases against women and racial biases favouring white people (Wan 2024). In the specific study, Wan points out that this is especially harmful in a medical context, where different groups of people may need different treatments or be more susceptible to certain conditions. Universities need to continue to foster different perspectives by getting students to understand why these biases occur. By creating a curiosity to investigate types of biases or compare materials and try to identify shortcomings through critical comparison, students can start to further understand what might be in the black box of information that AI is using to generate content.

Ethics

Understanding and being able to use AI also requires understanding the ethics behind the different uses. While a lot of the information presented by the generative AI is correct, and it can write a factual essay capable of passing a class, it is not ethical to do so. Becomes clear that they did not do the research themselves, because the sources do not exist. This is concerning because you have students who are not doing their research in the academic field, but rather just thinking that what the generative AI is feeding them is good enough (Brew et al. 2024). It shows a lack of editing and also discredits authors who do the work. If you are citing work from an author and saying it was written after that author passed away, you do not know the topic you are speaking about or are paying attention to the literature in that field.

Ways to Demonstrate Learning

Instead of testing students on memorization or facts, quizzes and tests might need to start being more critical thinking-focused, even for courses that originally were very fact-based. While this may require adapting by professors and other educators in university settings, it may be necessary to continue to foster literacy and learning skills (More & Bothe, 2024). Critical thinking is something that AI is currently unable to properly replicate and needs to be emphasized in post-secondary education (Larson et al. 2024). In a science class, instead of just giving the correct answer, explaining the meaning behind the answer and having to present an argument behind why you chose that over the other (Brew et al. 2023). Creating open book quizzes with questions that are very explicitly linked to in-class examples or stories, that can not be found on the internet or replicated by AI. Creating assignment criteria that already incorporate and require the use of AI, by having students write and submit prompts along with their work or having students use AI to hold interviews with historical figures and then critique the accuracy based on class recourses (Wan, 2024). By adapting classes and course assignments to include and embrace AI, students will be able to develop proactive AI Literacy skills and learn the best ways to navigate these platforms in different situations and with different instructions. This is also important as adapting and using AI in multiple different ways strengthens critical thinking skills.

Conclusion

Making sure that students continue to develop the skills needed to operate in the rapidly changing technology scene, by continuing to foster writing skills, problem-solving solving and real-world communication techniques (Berdahl, 2025). It is not enough for students to do one small lesson on AI literacy at the start of their degree, as by the time their degree finishes, there might be completely new limitations or uses for these platforms (Muller 2024). It is incredibly important that this education is ongoing and collaborative, with different perspectives, people and problems being discussed and taught throughout all levels and faculties of universities.

As these generative systems advance, systems that are specifically made for academic and research purposes will also advance (Sanchez et al. 2024). That is why universities need to continue to provide resources for the evolving digital age and focus on AI literacy as it continues to become more necessary. Proper research pathways need to be taught, and students need to be shown some of the ways that AI can both help their research journey and be harmful by supplying false or incorrect information. Students are in danger of losing some of their skills and abilities by creating a dependence on AI. Understanding the dangers of deskilling is important so that students can go forward knowing how to both retain and strengthen their existing literacy skills, instead of losing them to AI. In a technological world that is continuously advancing, it is hard to keep up with all of the new ways we can learn and communicate new information. By giving a foundation for people to build upon and explaining why it matters to stay up to date on these terms and understand the technologies, universities can continue to be places of learning and knowledge.

References

Berdahl, L. (2025, March 27). AI is transforming university teaching, but are we ready for it? University Affairs. https://universityaffairs.ca/opinion/ai-is-transforming-university-teaching-but-are-we-ready-for-it/

Brew, M., Taylor, S., Lam, R., Havemann, L., & Nerantzi, C. (2023). Towards Developing AI Literacy: Three Student Provocations on AI in Higher Education. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 18(2), 1–11. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.5281/zenodo.8032387

Chaudhuri, J., & Terrones, L. (2025). Reshaping Academic Library Information Literacy Programs in the Age of Chatgpt and Other Generative AI Technologies. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 29(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875301.2024.2400132

Ciampa, K., Wolfe, Z. M., & Bronstein, B. (2023). ChatGPT in Education: Transforming Digital Literacy Practices. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 67(3), 186–195. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1002/jaal.1310

Larson, B. Z., Moser, C., Caza, A., Muehlfeld, K., & Colombo, L. A. (2024). From the Editors: Critical Thinking in the Age of Generative Ai. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 23(3), 373–378. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.5465/amle.2024.0338

Marr, B. (2023, May 19). A Short History Of ChatGPT: How We Got To Where We Are Today. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2023/05/19/a-short-history-of-chatgpt-how-we-got-to-where-we-are-today/

More, M. M., & Bothe, S. (2024). Generative AI and ChatGPT in Industry and Education: Perspectives from Students, Educators and Industry Leaders. South Asian Journal of Management, 31(6), 9–28. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.62206/sajm.31.6.2024.9-28

Muller, C. (n.d.). AI On Campus: What It Means For Your College Investment. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/chrismuller/2024/10/03/ai-on-campus-what-it-means-for-your-college-investment/

Anastasia Olga (Olnancy) Tzirides, Gabriela Zapata, Nikoleta Polyxeni Kastania, Akash K. Saini, Vania Castro, Sakinah A. Ismael, Yu-ling You, Tamara Afonso dos Santos, Duane Searsmith, Casey O’Brien, Bill Cope, & Mary Kalantzis. (2024). Combining human and artificial intelligence for enhanced AI literacy in higher education. Computers and Education Open, 6(100184-). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2024.100184

Sánchez Gonzales, H. M., González, M. S., & Alonso-González, M. (2024). Artificial intelligence and disinformation literacy programmes used by European fact-checkers. Catalan Journal of Communication & Cultural Studies, 16(2), 237–255. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1386/cjcs_00111_1

Shu Wan. (2024). The Jack in the Black Box: Teaching College Students to Use ChatGPT Critically. Information Technology & Libraries, 43(3), 1–3. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.5860/ital.v43i3.17234