Kendra Funk

Kendra Funk is a fall 2024 graduate from the Bachelor of Psychology degree at Capilano University. She has been acknowledged on the dean’s list for consistently high grades over the course of her time at CapU. Her experience at school and work has led her to find a passion in working with kids, where she hopes to pursue a career in speech therapy. She would like to continue incorporating what she has learned from her studies into her future career.

For as long as I can remember, I have loved learning about language and the different ways we communicate as humans. This may in part be because talking came easily to me from an early age, in fact, many people thought I was older than I was because I spoke so clearly and concisely. However, my sister struggled with this more than most. She spoke late, and once she did, she had a speech impediment that caused her to become self conscious of speaking for a number of years. It wasn’t until she started seeing a speech therapist, and received the help she needed, that she started speaking with confidence. Conversely, my personal issues lied with reading. While other children seemed to advance with their abilities, I stayed behind, and started shying away from classwork. I felt dumb and incapable in comparison to my fellow classmates, and those feelings of insecurity took hold and shaped my schooling experience for years to come. Eventually, over the hours and years of practice, I found a love and appreciation for reading, but it was not an easy journey. I knew that when I got older, I wanted a job that would help mitigate those feelings of inadequacy in other children so they wouldn’t have to feel alone in their struggles like my sister and I often did. To provide this, my goal is to become a speech therapist and to create a space for children to feel confident in who they are. While not everyone has faced the same struggles with their speech and reading, I believe everyone can relate to feeling like they’re not good enough in certain aspects of their life. My hope for this paper is to convey the fundamental impact reading has on a person and their community.

Me and my sister. Image courtesy of Kendra Funk.

Setting the Scene:

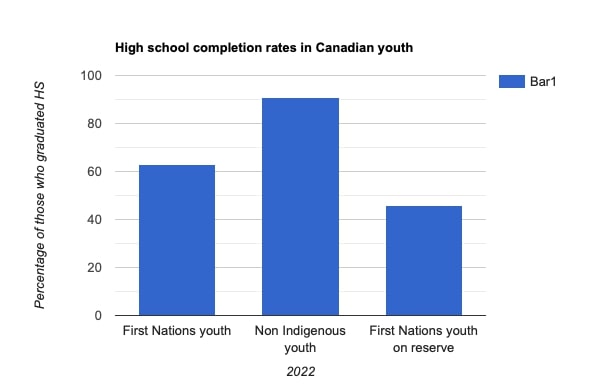

In the past number of years, reading scores amongst children have been in a serious decline. According to a 2020 study conducted by UNESCO and UNICEF, there has been a 20% jump in children experiencing reading difficulty, leading more than 100 million children to fall behind minimum proficiency levels worldwide (“100 million more children fail basic reading skills because of COVID-19”, 2021). In 2019, the Nation’s Report Card issued by the U.S. Department of Education found that more than 60% of U.S. public and non-public students were below grade level reading (“Failing grade: Literacy in America”, n.d.). The pandemic has not aided these issues either. Many schools experienced extended closures that impacted learning, and while remote instruction was widely used, it was not equal to in person-teaching. Multiple studies have documented that on average, U.S. students lost the equivalent of 1/3-1/2 a year of reading instruction (Barshay, et al., 2021). These low reading rates were highest amongst children in kindergarten to grade 2, which are some of the most vital years for foundational learning (“Failing grade: Literacy in America”, n.d.). Belonging to a lower socioeconomic status also plays a role in lowered reading levels, with studies showing that black and hispanic children are disproportionately more likely to face adverse socioeconomic circumstances than other ethnicities (“Failing grade: Literacy in America”, n.d.). While many of the studies that have been conducted occurred in the United States, Canada is not remotely exempt from these issues either. In Canada, the most impacted population is Indigenous people. According to Statistics Canada, 50% of Indigenous households had a serious literacy problem (Wetere, p. 4, 2011). This is not difficult to understand when high-school completion rates are lower in First Nations youth (63%) than in non-indigenous youth (91%) (Layton, 2023). What’s more is that those living on reserves had only a 46% high-school completion rate (Layton, 2023).

Graph of high school completion rate of non-indigenous youth, indigenous youth living off reserve, and indigenous youth living on reserve. Image courtesy of Kendra Funk.

Why these delays are happening:

There are many factors that contribute to these dropping rates, but across the board, kids are just not reading for pleasure as much as they once used to, with rates the lowest they’ve been in years. Among 13 year olds surveyed during the 2019-2020 year, only 17% said they read for fun, which is down from the 35% who did in 1984 (Schaeffer, 2021). This is important to note, as finding enjoyment in reading is not only crucial for children’s personal and educational development, but there is evidence to suggest that it is more essential for children’s educational success than their socioeconomic status (“Research evidence on reading for pleasure”, 2012). The increased use of technology has been at the forefront of the blame in the media for why these decreases are occurring. A study conducted by Pew Research Center in 2020 looked at how children under the age of 12 interact with technology. The overall most used mode was through TV, with 88% of parents saying their child engages in watching television, while 67% of parents say their child uses a tablet computer, and 60% said a smartphone. The age that children begin interacting with different smart devices is starting younger as well. Among the 60% of parents who report that their child uses a smartphone, 6 in 10 say their child began interacting with one before the age of 5, and 31% of that number say their child started before the age of 2. Not only are children engaging with their parents/older siblings’ smartphones, they also have their own device. As per the reports, 1 in 5 parents who have a child under the age of 11 say their children have a smartphone of their own. What is more, is that this increases the likelihood of children having social media platforms (despite age restrictions requiring users to be 13 before making an account), with 42% of these parents saying their child has a TikTok account and 31% stating their child has Snapchat. Notably, parents’ educational level impacts when their children begin interacting with smart devices. Parents with a high school education or less are almost twice as likely to say their child uses a smartphone in comparison to the parents with a college degree (21% vs. 11%) (Auxier et al., 2020).

All this to say, children’s use of smart devices in their daily lives has become the norm, however, the type of unfettered access children now have to technology is unprecedented, and because of this, it is not fully known what kind of long-term effects this will have on young attention spans as they get older (Betteridge et al., 2023). However, in the present day, shrinking attention spans in school aged children are already visible. From an early age, children are exposed to many different types of technological stimuli, often at the same time. This causes attention shifting, and these behaviours seep into other aspects of their lives, making children much more likely to seek out and respond to stimuli that provides them with instant gratification (Betteridge et al., 2023). This learned need for multitasking, coupled with having regular access to a device designed to distract them, makes it all the more difficult for children to engage with and comprehend long-form texts (“The impact of technology on reading habits and the future of reading”, 2023). Furthermore, long screen time exposure deeply affects executive functions in children, specifically in concentration and focus (Betteridge et al., 2023). This function is important for deciding which stimuli to pay attention to, and with the constant barrage of information vying for their attention, neurotypical children are beginning to display an inability to focus, similar to what is seen in children with ADHD (Betteridge et al., 2023). Technology use also releases dopamine, which activates reward systems in the brain every time children pick up a device, which over time, effectively alters their emotional, social and cognitive abilities (Betteridge et al., 2023). As content online moves towards more short form, 2 minute or less videos designed to include attention stealing stimulus, it is clear to see how activities that do not provide an instant dopamine rush are much less enticing.

On the surface, it seems probable that technology’s impact on attention spans could be the primary instigator as to why reading rates and scores are dropping, but the issue is much more nuanced than this. Generally speaking, students are slipping through the cracks, and those who should be receiving additional help simply are not, and instead, are being pushed forward without the necessary skills (Goldstein, 2022). Teacher shortages, budget cuts, and unparalleled enrolment growth have caused many classrooms across North America to become overcrowded, leading teachers to manage 30 plus students at a time (Ferguson, 2023). In B.C., according to their yearly union survey, 80% of teachers said they were unable to provide students with adequate support, leaving students with little to none of the 1-on-1 groundwork they need (Thayaparan, 2023). This, coupled with many educators not being properly trained in phonics and phonemic awareness (the basic, foundational understanding that is needed for reading in English), has only exacerbated the problem (Goldstein, 2022).

Environmental factors, such as differences in socioeconomic status (SES) is another huge, multi-faceted component contributing to the overarching issue at hand. Students belonging to lower SES families are less likely to have access to financial, social and educational resources, as well as less likely to receive early literacy and language exposure, which all cause variations in students’ reading abilities (Romeo, et al., 2022). The children hailing from socioeconomically disadvantaged families also have a higher likelihood of experiencing daily environmental stressors. In many cases, these parents are facing economic hardships that physically and emotionally limit them from being able to spend time with their children reading or being able to afford educational activities (Romeo, et al., 2022). These differences in reading abilities are apparent as early as kindergarten, with children from lower SES backgrounds demonstrating slower literacy progression overall. This is a major issue as kindergarten strongly predicts reading outcomes for 3rd and 4th grade (Romeo, et al., 2022). Aside from home environments differing, the quality of public education offered in lower SES areas is not equal to what is offered in higher SES neighbourhoods. Oftentimes, these schools are underfunded, and the instructors are not well-equipped in teaching the linguistic constructs that aid the most in literacy (Romeo, et al., 2022). In Canada, schools located on reserves are no exception to this rule. On average, these schools are paid 30% less by the federal government than what provincially funded schools are given off reserve, leaving school districts with a limited capacity to support these children (Porter, 2016). Furthermore, around 60% of First Nations children living on reserve are impoverished, making them overall twice as likely to live in poverty than non-Indigenous kids (Kirkup, 2016). This, and the systemic discrimination indigenous children face being enrolled in a system that did not have them in mind when they were constructed, and the mistrust and trauma caused by residential schools, has led to a major tossup on whether these children even complete their high-school education (Cummings, 2023).

Picture of an elementary school after news broke that 215 unidentified children’s bodies were found on the grounds of a previous residential school in BC. Image courtesy of Kendra Funk.

Why reading proficiency matters:

We all know that being able to read is an indispensable skill to have when it comes to communication, autonomy, and livelihood, but it is not one that everybody is afforded, even in the Global North. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 54% of American adults read below a 6th grade reading level, and 21% of those read below a 3rd grade level (Zauderer, 2023). In Canada, 48% of the adult population have literacy skills that are lower than a high-school level, while 17% of those score below the lowest functional level (“OECD skills outlook 2013: First results from the survey of adult skills”, 2013). While there are many factors that contribute to these numbers, some are attributed to high-school dropout rates. If students are not reading proficiently by grade 3, they are 4 times more likely to leave school without receiving a diploma. Of that population who have not graduated, 22% live in poverty versus 6% who do not (Chong, 2011). This does not just have an effect on the current population either, children of parents with low literacy rates have a 72% chance of also having a low literacy rate in adulthood (“Failing grade: Literacy in America”, n.d.). These rates negatively impact the economy, and with many jobs now requiring applicants to demonstrate an ability to read proficiently, previously employed people are out of jobs (Chin, 2021). With a higher unemployment rate, comes reduced income and augmented incarceration rates, which only perpetuates the cycle (“Failing grade: Literacy in America”, n.d.). A study done by the National Assessment of Adult Literacy found that if students could not read proficiently by 4th grade, they were 67% more likely to end up in jail or on welfare (“Early literacy connection to incarceration”, n.d.). Beyond these statistics, are the feelings of shame many people experience when they are unable to functionally read, with many hiding their impairments from others for years in fear of the judgement they might face (Chin, 2021). This has major consequences for such individuals, especially when it comes to making informed health, democratic, and economic decisions, which are basic rights everyone should have (Chin, 2021). Having the ability to read proficiently matters more than ever, and it is imperative that governments make concentrated efforts into alleviating these obstacles.

What is being done to help:

Thankfully, steps are being taken to help improve these issues in children and adults. Resources like the Canadian Children’s Literacy Foundation, ABC Life Literacy Canada, and United for Literacy support close to 30,000 children, youth and adults in over 200 different communities by providing free high-impact literacy programs (“Federal budget 2023: National literacy strategy”, 2023). Furthermore, the Government of Canada recently invested in new initiatives such as the Early Learning and Child Care (ELCC) and the Skills for Success Framework which both aim to provide provincial, territorial and Indigenous communities with access to affordable, high-quality child-care (“Early learning and child care”, 2023). Other strategies for children include teaching educators how to properly teach the 5 core components of reading instruction (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension), as well as providing better teaching resources for educators who have dyslexic students (Romeo, et al., 2022). For students from a lower SES background, some specific interventions have yielded the best results. These include physical intervention techniques like training parents and teachers to engage in enhanced storybook reading that encourage children to participate in the reading experience, offering summer programs that match students with reading material that interests them, and overall supplying a wide range of different educational resources, as well as providing emotional techniques like unconditional motivational support and modifying parental/child beliefs (Romeo, et al., 2022).

Children’s section of a library in White Rock, BC. Image courtesy of Kendra Funk.

While physical books and in person instruction remain the most powerful solution to combating dropping literacy rates, technology can be used by instructors and parents to their advantage (Starke, 2023). The internet provides a variety of different educational games and videos, as well as the ability for children to choose from a plethora of different books online. While these substitutions might seem counterintuitive when trying to get children to focus, they might actually make literacy more engaging and motivating for them (Starke, 2023). Technology also fosters collaboration, whether it be between educators, parents or children, there are many applications like Google Slides or Google Classroom that were designed to promote working in a team (Starke, 2023).

Communities themselves can also contribute to the cause, and one of the most beneficial things they can do is establish libraries. These structures are essential to communities as not only do they provide people with access to free books, but they are a main hub for educational and social resources (Bowman, n.d.). Whether that be through supplying technology or bringing people together through social events. Some of these social events can include story time reading, book clubs, and educationally centred youth activities (Bowman, n.d.). On a greater micro level, streets themselves can implement Little Free Libraries, which like its namesake, are little libraries in residential areas that offer free book sharing where anyone can take out or put in a book (“Little free library”, n.d.).

A Little Library located in Vancouver, BC. Image courtesy of Kendra Funk.

Chapter One, the job I currently work at as an early literacy interventionist, is one of such aforementioned literacy programs. Chapter One is a non-profit that works with primarily Indigenous children who might not otherwise have access to specialized literacy tutoring services. What the program offers is remote high-impact tutoring that helps students develop a strong phonics foundation and reading fluency through 1:1 instruction (“Our story”, n.d.). The Annenberg Institute National Students Support Accelerator conducted one of the largest randomized control studies, which looked at the effects of Chapter One’s high impact 1:1 tutoring program on children’s early reading skills. The results found that close to 70% of the students who were put into the treatment group had achieved benchmark phonic skills by the end of the year, compared to the 32% of students who were in the control group. When done again the following year, the results were nearly identical (“One of the largest randomized control trials of high impact tutoring for beginning reading”, 2023).

While the progress I have seen with the students I personally work with is anecdotal, the changes I have seen in a short amount of time are monumental for many of them. Developing those foundational phonic abilities provides them not only with the necessary skills to succeed, but the trust in themselves that they are capable.

Conclusion:

The journey to being able to read is deeply personal and transformative, and can shape your confidence, identity, and future. Facing the current stark disparities in literacy proficiency, which have been exacerbated by socioeconomic factors, educational inequities, and the pandemic, the urgency for effective interventions has never been more dire. Programs focusing on foundational skills, especially in early childhood, show that it is not only possible to bridge the reading gap but also to empower individuals and communities. It is imperative that the ongoing initiatives currently taking place become a widespread operation, so that people everywhere will have access to the help they need. My experiences, both personal and through my work with Chapter One, underscore the profound impact of targeted literacy support. Witnessing firsthand the transformative power of such interventions, where students not only learn to read but gain confidence in their abilities, has reinforced my commitment to this cause. The path toward literacy is not merely an academic one, instead, it’s a journey toward empowerment, equity, and fulfilment, paving the way for a brighter, more literate future for everyone.

References

Auxier, B., Anderson, M., Perrin, A., & Turner, E. (2020, July 28). Children’s use of technology and social media. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/07/28/childrens-engagement-with-digital-devices-screen-time/#:~:text=Among%20the%2060%25%20of%20parents,between%20ages%203%20and%204.

Barshay, J., Flynn, H., Sheasley, C., Richman, T., Bazzaz, D., & Griesbach R. (2021, November 10). America’s reading problem: Scores were dropping even before the pandemic. The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/americas-reading-problem-scores-were-dropping-even-before-the-pandemic/.

Betteridge, B., Chien, W., Hazels, E., & Simone, J. (2023, September 5). How does technology affect the attention spans of different age groups? OxJournal. https://www.oxjournal.org/how-does-technology-affect-the-attention-spans-of-different-age-groups/.

Bowman, S. L. (n.d.). How libraries nurture early literacy and a love for reading. Princh. Retrieved from https://princh.com/blog-how-libraries-nurture-early-literacy/.

Chin, F. (2021, January 17). Nearly half of adult Canadians struggle with literacy — and that’s bad for the economy. CBC Radio. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/costofliving/let-s-get-digital-from-bitcoin-to-stocktok-plus-what-low-literacy-means-for-canada-s-economy-1.5873703/nearly-half-of-adult-canadians-struggle-with-literacy-and-that-s-bad-for-the-economy-1.5873757?fbclid=IwAR2skBbg3F68XKcIYFmgx-fEc5_8cKO4k-QIrEX1op8FCFcn4rd3zDXK8GU.

Chong, S. (2011, April 8). Students who don’t read well in third grade are more likely to drop out or fail to finish school. The Annie E. Casey Foundation. https://www.aecf.org/blog/poverty-puts-struggling-readers-in-double-jeopardy-minorities-most-at-risk.

Cummings, M. (2023, January 25). Fewer than half of Indigenous students graduate on time from Edmonton public high schools. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/indigenous-students-high-school-completion-rates-1.6724969#:~:text=Systemic%20barriers&text=%22For%20Indigenous%20students%2C%20systemic%20discrimination,with%20Indigenous%20students%20in%20mind.

Early learning and child care. (2023, April 18). Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/early-learning-child-care-agreement/agreements-provinces-territories.html.

Early literacy connection to incarceration. (n.d.). Governor’s Early Literacy Foundation. https://governorsfoundation.org/gelf-articles/early-literacy-connection-toincarceration#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20National%20Assessment,system%20are%20functionally%20low%20literate.

Failing grade: Literacy in America. (n.d.). The Policy Circle. https://www.thepolicycircle.org/brief/literacy/.

Federal budget 2023: National literacy strategy. (2023, March 2). 125 United for Literacy. https://www.unitedforliteracy.ca/About/News/National-Literacy-Strategy#:~:text=ABC%20Life%20Literacy%20Canada%2C%20the,under%2Drepresented%20groups%20in%20Canada.

Ferguson, E. (2023, September 15). Overcrowded schools see kids sharing desks, learning in staff rooms and hallways. Calgary Herald. https://calgaryherald.com/news/local-news/overcrowded-schools-calgary-board-education-classrooms-overflow.

Goldstein, D. (2022, March 8). It’s ‘alarming’: children are severely behind in reading. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/08/us/pandemic-schools-reading-crisis.html.

The impact of technology on reading habits and the future of reading. (2023, November 22). Technology Org. https://www.technology.org/2023/11/22/the-impact-of-technology-on-reading-habits-and-the-future-of-reading/.

Kirkup, K. (2016, May 16). 60% of First Nations children on reserve live in poverty, institute says. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/institute-says-60-percent-fn-children-on-reserve-live-in-poverty-1.3585105.

Layton, J. (2023, June 21). First Nations youth: Experience and outcomes in secondary and postsecondary learning. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/81-599-x/81-599-x2023001-eng.htm.

Little free library. (n.d.). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Free_Library.

OECD skills outlook 2013: First results from the survey of adult skills. (2013). OECD. https://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/Skills%20volume%201%20(eng)–full%20v12–eBook%20(04%2011%202013).pdf.

One of the largest randomized control trials of high impact tutoring for beginning reading. (2023, February 23). Chapter One. https://www.chapterone.org/ca/one-of-the-largest-randomized-control-trials-of-high-impact-tutoring-for-beginning-reading?__geom=%E2%9C%AA.

Our story. (n.d.). Chapter One. Retrieved from https://www.chapterone.org/ca/about.

Porter, J. (2016, May 17). First Nations students get 30 per cent less funding than other children, economist says. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/first-nations-education-funding-gap-1.3487822.

Research evidence on reading for pleasure. (2012, May 15). GOV. UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/research-evidence-on-reading-for-pleasure.

Romeo, R., Uchida, L., & Christodoulou, J. (2022). Socioeconomic status and reading outcomes: Neurobiological and behavioral correlates. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 183, 57-70. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20475.

Schaeffer, K. (2021, November 12). Among many U.S. children, reading for fun has become less common, federal data shows. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/11/12/among-many-u-s-children-reading-for-fun-has-become-less-common-federal-data-shows/.

Starke, K. (2023, September 13). The role of technology in literacy development. Graduate Programs for educators. https://www.graduateprogram.org/2023/09/the-role-of-technology-in-literacy-development/#:~:text=There%20are%20some%20benefits%20of,engaging%20and%20motivating%20for%20students.

Thayaparan, A. (2023, September 5). B.C. starts another academic year facing overcrowded, understaffed schools. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/overcrowded-understaffed-bc-school-year-1.6956595.

Wetere, R. (2011). Addressing the literacy issues of Canada’s Aboriginal population: A discussion paper. ArrowMight Canada. http://en.copian.ca/library/research/issues_aboriginal/issues_aboriginal.pdf.

Zauderer, S. (2023, June 30). 55 US literacy statistics: Literacy rate, average reading level. Cross River Therapy. https://www.crossrivertherapy.com/research/literacy-statistics#:~:text=Nationwide%2C%20on%20average%2C%2079%25,literacy%20below%20sixth%2Dgrade%20level.

100 million more children fail basic reading skills because of COVID-19. (2021, March 26). UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/03/1088392.