Sophia Goto

Sophia is completing a BA in Psychology at Capilano University. She is an experienced educational assistant and a lifelong athlete. Upon completing her degree, she plans to pursue an MA in Counselling Psychology in order to prepare her for a career of supporting individuals who may be facing mental health challenges.

While my athletic career has produced many of my greatest accomplishments, it has also resulted in countless injuries and much heartbreak. With every head injury I’ve endured, I’ve strayed further from who I once was, and I’m not sure that I’ll ever be the same person again. In 2018, I was playing my second year of collegiate soccer at Capilano University. After spending most of my first year on the bench, I had finally earned my position on the starting lineup. In the first few minutes of the first game of the season, I collided head on with a player from the opposing team. I got up off the pitch feeling nauseous and confused, but I was assured by my coach and team trainer that I was fine, and it was nothing more than a minor head bump. I knew something was wrong, but I couldn’t fathom returning to the bench and giving up my highly coveted spot. With minor symptoms, I continued to train in the coming days. In the following game, only a week later, I lost consciousness after being punched in the head by my goalkeeper while we attempted to defend a corner kick. The symptoms that arose after this incident were far too extreme for anyone to ignore, and I was forced to take time off school, soccer, and work. After seeking treatment, I discovered how serious it was that I had experienced multiple concussions in such a short period of time. Now, years, later, I am still coping with some of these symptoms. As a young person who has suffered four concussions now, I wonder what could have been done differently. Why was my health sacrificed for the good of the team? What changes need to take place within the athletic community so that young athletes don’t fall victim to the same circumstances?

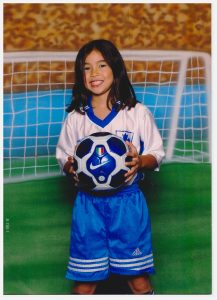

Always the competitive athlete, I started playing soccer at age four and continue to play today. (Photo credits: Sophia Goto)

A concussion is usually described in the medical setting as a “mild” brain injury (CDC, 2019). As a result, they are treated as mild injuries by patients, medical personnel, and the entire athletic community. Concussions are generally caused by any type of force to the head that results in the brain bouncing around within the skull, damaging certain structures in the process (CDC, 2019). The most common symptoms associated with head injury are all too familiar for me—confusion, headaches, loss of consciousness. According to Lesley Schimanski, a behavioral neuroscientist at Capilano University, concussion symptoms are highly variable and depend on the severity of the injury. Emotional symptoms are also stereotypical: “Mood changes in the period after are super common—so rapid mood swings, less control of one’s emotions, but also perception of emotion can be affected.”

Historically, concussions have been difficult to diagnose, although the diagnosing process has evolved over time. By the 1970s, concussions were primarily defined by loss of consciousness, illustrating an emphasis placed on observable symptoms. Nearing the 2000s, concussion diagnosis rested on the assignment of a degree of severity that would outline return to play protocol in a one-size-fits-all fashion (Williams & Danan, 2016). Today, the diagnosis for concussion has evolved to encompass a wide range of symptoms including changes in vision, hearing, strength, sensation, balance, coordination, and reflexes (MFMER, 2022). Typically, concussions are not detectable by brain imaging, which plays a key role in the difficulty of accurately diagnosing these injuries. Over the last decade, the world has seen substantial growth in the amount of media coverage, research, and educational material geared towards addressing concussion in sport. Protective equipment in sport is more advanced than ever and ground-breaking research is being conducted on biomarkers of head injury. Despite the recent trend in a hopeful direction, concussions continue to be misdiagnosed, misunderstood, and downplayed by those who experience them (Sarmiento et al., 2017). Within the academic community, symptoms of head injuries appear to be fairly well-understood. In stark contrast, the lack of awareness surrounding head injuries is all too common in sport. A recent review of current research suggests that amongst most sports coaches and match officials, concussion knowledge is moderate at best (Yeo et al., 2020).

Despite injury and heartbreak, soccer is the source of some of my happiest memories. (Photo credits: Sophia Goto)

In Canada alone, roughly 200,000 concussions are reported annually (Brain Injury Canada, 2022). However, studies estimate that half of all concussions acquired through sport remain unreported. Before the 1950s, the topic of head injury in sport was granted minimal attention until fatal cases began to appear. As sports-related deaths and head injury gained more recognition, especially in American Football, the helmet was introduced in 1951, signifying a major milestone for the athletic community. Despite its introduction, and until rules of the game were altered, a temporary increase in head injury took place in football as the helmet facilitated more reckless play (Williams & Danan, 2016). For decades, professional sports committees implemented loose protocol concerning concussion management and little understanding of long-term implications of such injuries remained. In 2001, the first International Meeting on Concussion in sport was held in Vienna in order to improve safety for athletes in various sports (Damji & Babul, 2018). Although the meeting signified a shift towards recognizing the severity of head injury, there was still inadequate understanding of long-term prognoses and the definition of concussion across stakeholders remained inconsistent.

Taken in hospital following my most recent head injury, I did not know at the time that my symptoms would be long-lasting. (Photo credits: Sophia Goto)

Concussion protocol in sport reflects willful ignorance of the professional athletic community. With surmounting evidence on the risks of repeated head injury, major sports associations should be making changes to concussion protocol. However, in response to the growing body of research, the NFL initiated an independent committee and produced their own studies that downplayed the risks of concussion in order to shift attention away from the topic (Chen, 2023). Tua Tagovailoa’s experience is a perfect reflection of the NFL’s tendency to prioritize winning over players’ health. In late September of 2022, Tagovailoa of the Miami Dolphins suffered a head injury when he was tackled during a match. It was similar to a hit he had taken only four days earlier during another game. Neuroscientist Julie Stamm, an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin, explains that it can typically take around two weeks for the brain to return to baseline conditions after an injury (Foster, 2022). It’s puzzling then that Tagovailoa would be cleared to play only days later. Chris Nowinski (PhD), CEO of the Concussion Legacy Foundation, said Tagovailoa’s original injury caused clear signs of concussion and he should have never been playing in the following game (Quaisar, 2022). Many other experts agree with Nowinski and the focus has since shifted on how exactly Tagovailoa was cleared to play. Was it his fault for failing to advocate for himself or is the organization to blame for consistently trying to minimize signs of concussion?

While the NFL is currently in its off-season, Tagovailoa reportedly cleared concussion protocol in February of this year and is expected to play come the start of the new season this fall (Baer, 2023). Despite hopeful attitudes that he will soon be able to participate fully again, it’s tough for anyone to deny the heightened risks he faces. Tagovailoa sustained multiple significant head injuries during the 2022 season and spent over thirty days in concussion protocol, suggesting that his concussion was severe. Even if he recovers fully, a patient who has experienced a previous concussion will always be more susceptible to subsequent head injuries than someone who hasn’t had one (Allen, 2022). Repeated concussions undoubtedly take a heavy toll on the body. They can cause dysfunction in autonomic nervous system processes, vision, and hormonal function. The symptoms of multiple concussions are more noticeable and usually take longer to recover from than a single head injury (Allen, 2022). Had Tagovailoa taken a longer break following his first head injury, he may have recovered quicker as well. Research suggests that overall, amongst athletes who have sustained a head injury, those that immediately removed themselves from activity were able to return to sport earlier than those that continued to play (Asken et al., 2016). On the other hand, athletes that tried to continue playing immediately after a head injury were more than twice as likely to experience a prolonged recovery.

In the professional and collegiate sport settings, it’s easier to appreciate that stakes are high and the pressure placed on athletes, coaches, and team staff is intense. However, even in the recreational sport setting, it’s common for athletes to ignore serious injuries to benefit the team. To explore this occurrence, I met with Patrick Hanlon, a 22 year-old soccer player who resides on the North Shore. Patrick sustained an initial head injury while cliff jumping with friends in Lion’s Bay, North Vancouver. He recalls smacking his face on the water, but when he resurfaced, he and his friends laughed it off. Despite the lingering pain he experienced in the following days, Patrick didn’t think much of it. “I didn’t know I was concussed so I kept playing soccer, I kept doing things”, he recalls regretfully. Patrick’s inability to identify his own concussion highlights the gap in knowledge amongst athletes at all levels of play. When his condition didn’t improve, Patrick was forced to seek treatment, but he admits to downplaying his symptoms. “I tried to convince myself I was okay so I could get back to soccer sooner”, he recollects. The culture surrounding injury on Patrick’s soccer team didn’t help. He explains that sustaining multiple concussions has become somewhat of a joke to his teammates. His own goalkeeper had experienced “Upwards of 10 concussions”, but had ultimately lost count. “People can convince themselves that they’re fine if it means they get to keep doing what they love”, is how Patrick summarizes his own unwillingness to come to terms with the severity of his head injuries.

Patrick Hanlon is a lifelong athlete who, like myself, has experienced numerous head injuries acquired through sport. (Photo credits: Patrick Hanlon)

Patrick realized the seriousness of his concussion when his symptoms started to impact his relationships. Through teary eyes, he recalls a comment from his father that has stuck with him throughout his recovery, “You’re different since your concussion.” His father’s seemingly harmless comment highlights Patrick’s own inability to recognize the severity of his symptoms. Patrick and I agreed that while the emotional implications of our head injuries have been the most challenging to navigate, they were also the least expected. While Patrick’s emotional changes have mostly resulted in heightened irritability, my own symptoms have included breaking out into tears at random times. Although we are of similar age and have had a similar amount of concussions, our symptomatic differences highlight the enormous variability when it comes to head injury. Like Patrick, my own recovery is ongoing, months after my most recent concussion and years after my initial injuries. While most of my physical injuries have healed, the emotional repercussions haven’t subsided, and I’m not sure when or if they will. My own recent concussion-related visit to hospital resulted in nothing more than a few hours of morphine and a pamphlet outlining standard concussion protocol. The following morning, in alignment with typical concussion symptoms, I would forget most details of my hospital visit.

According to Dr. Lesley Schimanski, the emotional changes caused by head injury can take the longest to subside. When her own daughter fell and hit her head on a playground two years ago, Dr. Schimanski rushed her to emergency to be evaluated. Since her injuries were seemingly minor, she was sent home from hospital with a familiar pamphlet and told to “take it easy for a couple weeks”, reflecting lack of concern surrounding mild-seeming head injury on the part of emergency care staff. Taking her daughter to their family physician led to no further investigation either. Dr. Schimanski claims her daughter “Wasn’t acting like herself, to the point where other people were noticing too.” Again, Dr. Schimanski’s description of her daughter’s personality changes highlight symptoms that are easily overlooked by medical personnel but are noticeable to family and friends. Despite her concerns, she was brushed off by healthcare practitioners and was ultimately forced to take her daughter home and let the symptoms run their course. While the headaches had subsided by about a year later, her daughter is just getting past the emotional changes today. Based on her daughter’s experience and my own experience, Dr. Schimanski argues that there’s room for improvement in the treatment of brain injury, especially in terms of the milder forms. With major brain impacts, the treatment protocols are obvious, but with concussion, “It just doesn’t seem well-understood or well-followed up on in our healthcare system.” It seems as though, once you are rushed out of hospital, your treatment is likely to end there.

Dr. Lesley Schimanski is a mother, a Capilano University Psychology professor, and a specialist in behavioural neuroscience. (Photo credits: Steph Townsend)

Through my research, I have discovered some obvious gaps in the knowledge surrounding concussion that should be addressed if outcomes for head injury patients should ever look more hopeful. Research suggests that concussion knowledge alone does not influence athletes’ disclosure as much as situational contexts and stakeholder attitudes (Conway et al., 2020). Although the knowledge surrounding concussion is inconsistent within the athletic community, stakeholder—team owners, staff, even parents—attitudes are equally to blame for the lack of care for injured athletes. The high pressure placed on athletes by their coaches, parents, and trainers, results in players sidelining their own health for the sake of the team (Cusimano et al., 2017). Especially in the professional setting, players try to downplay and hide their concussion incidences for fear that it might tarnish their athletic reputation. Fear of publication upholds this stigma in high-stakes contexts (Wolverton, 2015).

Often, individuals who have experienced a concussion hold the strongest knowledge about them (Cusimano et al., 2017). Research points to the bleak reality that there is not enough education regarding head injuries until they have been acquired. Concussion education appears to be more reactive than proactive, but this approach puts all Canadians at risk. By introducing frequently updated concussion education in both school and sports settings, Canadians can learn about crucial, preventative measures that mitigate the risk of head injury, such as proper helmet usage. Where concussion education already exists, it is unequal between populations. In NCAA sports, research has found that Black athletes consistently display lower concussion knowledge than their white counterparts despite NCAA concussion education requirements for all athletes. The implications for these findings are detrimental, considering that non-white athletes are also less likely to seek care for their injuries than white athletes (Wallace, 2021). Research also suggests that female athletes are more susceptible to head injury and more likely to experience worse symptoms than their male counterparts (McGroarty et al., 2020). As a female athlete of Asian descent, it’s both frustrating and disheartening to learn that when it comes to head injury, young athletes that look like me may be not be acquiring the same concussion knowledge as white, male athletes.

As knowledge surrounding concussions continues to grow, new consequences of head injury are still being explored today. CTE is a rather recent finding that accounts for a large portion of research being conducted today. CTE, or chronic traumatic encephalopathy, is a brain disease that is thought to be linked to repeated head injury (NHS, 2022). Although the condition is rare and not well-understood, experts agree that hallmark symptoms of CTE include cognitive impairment, behavioral changes, mood disorders, and motor symptoms. While this disease is most likely caused by successive head injuries earlier in life, the disease itself doesn’t usually appear until late adulthood (MFMER, 2022). According to Dr. Schimanski, the microscopic brain damage caused by CTE looks “a lot like what happens in dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.” As a result, symptoms tend to overlap. A recent study found that in a sample of almost 380 brains of former NFL players, over 90% showed signs of the disease (Mann, 2023). The greatest issue surrounding CTE at the moment is that it is only diagnosable post-mortem. With more research, experts hope to find a way to diagnose CTE in the living brain. Some research already suggests that MRI technology may aid in this hope (Boston University School of Medicine, 2021).

Regardless of current issues surrounding concussion knowledge, the future of brain injury research and management seems hopeful as various forms of technology continue to develop. Virtual reality, a rather recent advancement in technology, has shown potential in further advancing the diagnosing process of head injury. In one recent, groundbreaking study, researchers used virtual reality and a moving platform to compare balance in concussed versus non-concussed subjects (Jacob et al., 2022). The data gathered allowed researchers to distinguish between concussion patients and their healthy counterparts with upwards of 90 percent accuracy. While the study is limited to balance-related symptoms of head injury, it represents a shift towards the quantifiable assessment of concussions. Research suggests that as new tools, such as biomarkers and head impact sensors continue to develop, so too will the diagnosing and treatment plans in regards to concussion. Such developments will require additional funding and the ongoing dedication of researchers in the field.

Lack of concussion knowledge seems to extend far beyond my own experience. Sports-related concussion knowledge, or lack of rather, is rooted in stigma surrounding the unseen symptoms of head injury, ongoing challenges in diagnosing, and dangerous attitudes held by the entire athletic community. Concussion research is important, not only in the sport setting, but for the wellbeing of the entire population as concussions effect individuals of all ages and their families. As research in the field continues, I hope that treatment plans will become more specialized and be taken more seriously by patients. According to Dr. Schimanski, future research could “Help create different pathways for treatment that could be more clear to both caregivers and patients.” I hope that by educating themselves on the risks of head injury, those who experience them will be more driven to advocate for their health. Even more so, it’s imperative that a shift occurs in the way we acknowledge head injury, especially within the athletic community. When I experienced subsequent concussions during my collegiate soccer career, too much pressure was placed on me to sacrifice my own health for the sake of the team’s success. Ultimately, athletes should not be the ones making these decisions, because passionate players will choose sport over health whenever possible. It’s likely that in the near future, diagnosing a concussion will be as simple as taking a temperature. Until that day, we all have a part to play in taking head injuries more seriously.

In the athletic community, it would appear as though the individual does not matter as much as the good of the team. (Photo credits: Sophia Goto)

References

Baer, J. (2023, February). Tua Tagovailoa reportedly clears concussion protocol 38 days after most recent head injury. Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved March 27, 2023, from https://ca.sports.yahoo.com/news/tua-tagovailoa-reportedly-clears-concussion-protocol-38-days-after-most-recent-head-injury-191508586.html?guccounter=1#:~:text=Tua%20Tagovailoa%20had%20multiple%20significant,season%20he%20had%20last%20year

Boston University School of Medicine. (2021, December 8). MRI’s may be initial window into CTE diagnosis in living; approach may shave years off diagnosis. ScienceDaily. Retrieved March 27, 2023, from https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2021/12/211208090130.htm

Brain Injury Canada. (2020, October 15). Statistics on brain injury. Brain Injury Canada. Retrieved February 24, 2023, from https://braininjurycanada.ca/en/blog/2020/10/15/statistics/#:~:text=There%20are%20200%2C000%20concussions%20annually,and%20manage%20%5B21%5D.%E2%80%9D

Chen, I. (2023, February 11). The forgotten history of head injuries in sports. The New Yorker. Retrieved February 28, 2023, from https://www.newyorker.com/news/annals-of-inquiry/the-forgotten-history-of-head-injuries-in-sports

CDC. (2019, February 12). What is a concussion? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 27, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/headsup/basics/concussion_whatis.html#:~:text=Print-,What%20Is%20a%20Concussion%3F,move%20rapidly%20back%20and%20forth

Cusimano, M. D., Topolovec-Vranic, J., Zhang, S., Mullen, S. J., Wong, M., & Ilie, G. (2017). Factors influencing the underreporting of concussion in sports. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 27(4), 375–380. https://doi.org/10.1097/jsm.0000000000000372

Damji, F., & Babul, S. (2018). Improving and standardizing concussion education and care: A Canadian experience. Concussion, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.2217/cnc-2018-0007

Foster, M. (2022, October 19). Tua Tagovailoa reveals he doesn’t remember being carted off the field after concussion. CNN. Retrieved March 27, 2023, from https://www.cnn.com/2022/10/19/sport/nfl-tua-tagovailoa-concussion-spt-intl/index.html#:~:text=The%20investigation%20into%20Tagovailoa’s%20first,then%20played%20four%20days%20later

Jacob, D., Unnsteinsdóttir Kristensen, I. S., Aubonnet, R., Recenti, M., Donisi, L., Ricciardi, C., Svansson, H. Á., Agnarsdóttir, S., Colacino, A., Jónsdóttir, M. K., Kristjánsdóttir, H., Sigurjónsdóttir, H. Á., Cesarelli, M., Eggertsdóttir Claessen, L. Ó., Hassan, M., Petersen, H., & Gargiulo, P. (2022). Towards defining biomarkers to evaluate concussions using virtual reality and a moving platform (BioVRSea). Scientific Reports, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12822-0

Mann, D. (2023). In autopsy study, over 90% of former NFL players showed signs of brain … U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved March 27, 2023, from https://www.usnews.com/news/health-news/articles/2023-02-09/in-autopsy-study-over-90-of-former-nfl-players-showed-signs-of-brain-disease-cte

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2022, February 17). Concussion. Retrieved February 25, 2023, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/concussion/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20355600#:~:text=Brain%20imaging%20may%20determine%20whether,of%20your%20skull%20and%20brain.

McGroarty, N. K., Brown, S. M., & Mulcahey, M. K. (2020, July 16). Sport-related concussion in female athletes: A systematic review. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine. Retrieved April 1, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7366411/

NHS. (2022). Chronic traumatic encephalopathy. NHS choices. Retrieved March 27, 2023, from https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/chronic-traumatic-encephalopathy/#:~:text=Chronic%20traumatic%20encephalopathy%20(CTE)%20is,support%20can%20manage%20the%20symptoms

Quaisar, M. (2022, October 6). The NFL should reevaluate its concussion protocol. The Berkeley Beacon. Retrieved February 28, 2023, from https://berkeleybeacon.com/the-nfl-should-reevaluate-its-concussion-protocol/

Sarmiento, K., Donnell, Z., & Hoffman, R. (2017). A scoping review to address the culture of concussion in youth and high school sports. Journal of School Health, 87(10), 790–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12552

Williams, V. B., & Danan, I. J. (2016). A historical perspective on sports concussion: Where we have been and where we are going. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 20(43). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-016-0569-5

Wolverton, B. (2015, March 2). In football, stigma of concussion creates incentives to hide it. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved February 23, 2023, from https://www.chronicle.com/article/in-football-stigma-of-concussion-creates-incentives-to-hide-it/?emailConfirmed=true&supportSignUp=true&supportForgotPassword=true&email=sophiagoto%40gmail.com&success=true&code=success&bc_nonce=l2vjrq22uqc7xipz9mj4&cid=gen_sign_in

Yeo, P. C., Yeo, E., Probert, J., Sim, S., & Sirisena, D. (2020). A Systematic Review and Qualitative Analysis of Concussion Knowledge amongst Sports Coaches and Match Officials. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 19(1), 65–77.