Anita Jheeta

Anita Jheeta is completing the Engineering Transition Diploma and a BA in Psychology at Capilano University. Anita currently works as an administrative assistant at a Law Firm. She hopes to further her education by obtaining a JD, and ultimately a PhD, so she can be a professor.

“Where’s the other two percent” – My parents after I got a mark of 98% on a test.

Regardless of how well I did in school, if it wasn’t 100%, it wasn’t enough. I’m a second generation Canadian, so perfection was the only expectation for me. In education, that meant nothing below 100%, career wise I had three options: doctor, lawyer, or engineer. For a long time, I was fine with those expectations of perfection. I understand that my family sacrificed their lives for the next generations. My dad was a child when his family came to Canada. His parents could only afford to share one bedroom in a basement with their three young kids. They had to depend on strangers after my grandpa’s family left them with nothing but their clothes. My mom “Neesha” was an adult when her family came to Canada. She was a professor in India but had to work minimum wage at the Vancouver Airport because she had no other choice. Her family was very comfortable in Punjab but sacrificed it all to have a better life in Canada. In their view, being a doctor, lawyer, or engineer means respect, it means being comfortable financially, and it means independence. It means gaining the three things that they gave up to ensure my generation has a better life than they did. So, I grew up dreaming of being a lawyer.

The first academic award I received at 5 years old. From this point on my family expected me to always do extremely well in academics.

For me, perfection was defined by my parents and the societal expectations set for me.

As a woman in a desi household, my number one goal was to make/ keep everyone else happy no matter what. The only way to be perfect was to please everyone else, especially in academics. I have wanted to be a lawyer since I was a child, for two reasons. The first was when I was four, my grandma was in a legal battle with two of her sons. Consequently, I would spend a lot of time in her lawyer’s office. He was a great lawyer who brought peace to my grandma in some of the hardest years of her life. I’ve wanted to be a lawyer like him, one that helps people in some of their worst times. The second reason: whenever I said I wanted to be a veterinarian, a marine biologist, or a musician, my dad would say “You should be a corporate lawyer because you can make a lot of money and it would make everyone really proud of you.”

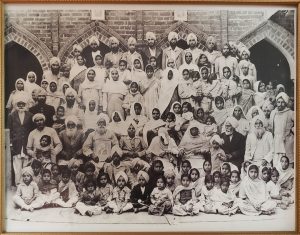

My grandpa’s (on my dad’s side) family photo taken in the mid-thirties in Punjab, India. This is the last photo taken of his entire family.

My understanding of the culture of the legal profession is that it is a profession known for working extended hours, while striving to meet perfectionist standards of clients to deliver a document in two days that looks like it has been worked on for seven days, the entire time. Honestly, I’ve been having doubts about pursuing law for a career since I started working as an administrative as a law firm. Many times, I wonder if I genuinely want the life my boss has, working 12-hour days feeling stress constantly. Therefore, this article is going to explore the legal profession with a focus on the perfectionist aspect of it, because I really don’t know if it’s the career I’ve genuinely wanted or if it was wanted for the ‘perfect’ me.

P.M. (name redacted) is a 26-year-old lawyer who completed his LLB at Durham University in London. He works as part of a team in a large international firm and he specializes in Corporate Mergers and Acquisitions/ Structured Finance. I’ve known P.M. since elementary school. He was my brother’s best friend when we were younger, and I looked up to him at one point because, as my parents have said, “No kid is perfect, but P.M. is close.” P.M. describes perfection as “An unattainable goal worth striving for.” In regards to perfectionism in law, he goes on to say that “Lawyers get paid high salaries for not making mistakes. Much of the value of a lawyer has to do with precision, accuracy and getting things right. Lawyers are held to a very high standard.” In other words, lawyers are expected to be perfect, by clients who pay, and by firms that bill. Law firms are competitive in nature. The competitiveness between lawyers and law firms who look to outdo their competitors fuels perfectionist ideals among staff, which increases fear of making mistakes (Gazica). Law firms should nurture the wellbeing of their staff to counter this competitive, perfectionist culture they create. However, as quoted by Cadieux et al., (32) an anonymous lawyer states that “The profession is broken. The pressure to meet billable hours and the expectation to be constantly available to senior lawyers have caused [them] serious mental health problems…[their] health insurance barely covers the medication [they’ve] had to go on just to be able to do this job.” This lawyer goes on to say that they can’t afford therapy and that “The profession is all talk: firms do not actually care about the mental health of [their] employees” (Cadieux et al., p.32). Cadieux et al., quotes another anonymous lawyer who says the legal profession is subjected to “An epidemic of lack of empathy and expectation to work harder” (Cadieux et al., 45). The expectation to meet billable hours mixed with the lack of empathy from other lawyers who are consistently meeting their hours can contribute to an unhealthy work culture within the legal field. Teams excel when they work together towards a common goal. If you’re constantly in competition with your team members, healthy group dynamics are challenged.

P.M. also touches on the working stereotypes that lawyers are subjected to from an outsider perspective by saying that “The issue [with these stereotypes] concerns the understanding that a lay person lacks in relation to the working realities and responsibilities of a lawyer. In the past, [he has] been told by well-meaning individuals that [he] should ‘get a hobby’ as a solution to [his] long working hours. In reality, the hours that [he] works are not of [his] choosing and [he has] ethical and professional responsibilities that must be met.”

I am not sure if I want to manage this expectation to work these hours to be a perfect lawyer for the rest of my life. As soon as I started engineering in university, my ability to strive for perfection disappeared. I had to come to terms with the fact that I had no idea how to get perfect grades. I went from graduating high school with honours to getting the worst GPA of my life in the same calendar year. My mental health deteriorated during the first year and a half of university because I wasn’t meeting my definition of a perfect GPA (4.0 – 4.33) and I was stressed because I thought I was letting myself, my parents, and my people (who are known “to be very smart and good at maths”) down. My health was so bad I even lost half of my hair during this period. However, I will say thank you to my brother for the comedic relief of “C’s get degrees” every time I got upset when I got a mark that was below my expectations. At the time I didn’t realize it, but he was helping me find balance. My older brother was telling me that it was okay not to be perfect.

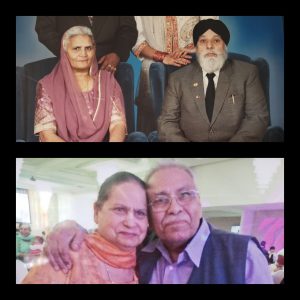

My grandparents from both my mom’s side and my dad’s side.

My boss had also struggled with perfectionism in academics. My boss, A.F. (name redacted), has 38 years of experience in the legal field. He completed his B.A. at the University of Toronto and his LLB at UBC. Mainly as a sole practitioner specializing in Estate law, he helps people in some of the worst times of their life, after losing a loved one. He is a great lawyer who puts his clients’ needs before his own. I can see this when I look at his work schedule that starts at 5 am and usually ends around 6pm. He has told me that the concept of perfection does not affect him because he knows mistakes are going to happen and the only thing we can do is try our best and fix mistakes when they happen. But I have literally never seen him make a mistake. If he does make mistakes, he fixes them before others notice. It’s important to note that perfectionism is not always a bad thing. We all aspire to achieve different things based on our aspirations (Hewitt and Gordon). In that sense, it’s a driving factor when you want to do well in something. I wanted to do well in high school to get into university, and it worked. I got into every school I applied to.

However, as paraphrased by Gazica, self‐oriented perfectionism and socially prescribed perfectionism are the two forms of perfection that consistently relate to individual health and well‐being outcomes (Chang) (Gazica). Self-oriented perfectionism can be described as setting high standards and being overly critical of yourself (Gazica). Socially prescribed perfectionism is when you feel the need to be perfect to gain acceptance from others (Gazica). The common factor with both types of perfectionism is that it makes you criticize yourself immensely (Gazica). In my case, I constantly thought I was a failure during my first couple years of university because my marks weren’t high enough to meet the standards of perfection in my life. The negative side of perfectionism is that it has been linked to negative outcomes “…Including characterological feelings of failure, guilt, indecisiveness, procrastination, shame, and low self-esteem” (Chang). These feelings are associated with psychological distress which can be described as “…An unpleasant subjective state that combines a set of physical, psychological and behavioural symptoms which cannot be attributed to a specific pathology or disease” (Cadieux et al., p.27). Now, everyone will experience psychological distress in their lives. When you lose a loved one, you’re going to feel psychological distress, there’s no way around it and there is no shame experiencing it. It just shows that our bodies are experiencing changes due to external factors. In relation, the symptoms of psychological stress can vary in response to the intensity of the stressors you are experiencing (Cadieux et al., p.28).

However, when it comes to career choice, “The proportion of psychological distress observed among legal professionals is higher than in the working population in Canada” (Cadieux et al., p.30). According to Statistics Canada, as cited by Cadieux et al., p.36, between September and December of 2020, around 15% of Canadians were affected by major depressive disorder and 13% were affected by generalized anxiety disorder (Cadieux et al., p.36). In comparison, during the same period, 28.6 % of Canadian legal professionals were affected by major depressive disorder and 35.7% were affected by generalized anxiety disorder (Cadieux et al., p.36). Another anonymous lawyer tells Cadieux et al., (44) that they attribute their anxiety and depression because they feel like a failure (Cadieux et al., p.44). This lawyer says that they end up berating themselves if they don’t get the result that they, or their client want (Cadieux et al., p.44). Even if they do meet expectations, they berate themselves because they weren’t perfect, because they could have aimed higher (Cadieux et al., p.44). The same lawyer also bravely admitted that they experienced intrusive thoughts of self-harm and suicide during incredibly stressful times of their career and through the pandemic (Cadieux et al., p.44). When you have set high expectations for yourself to be perfect, anything that comes in the way of your perfectionism may negatively affect your wellbeing and cause negative self-perceptions.

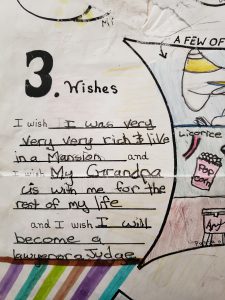

My wishes from when I was 10 years old. This was part of an assignment where we were supposed to make a poster of ourselves. My grandma kept this in her room.

Unfortunately, perfectionism is also associated with “more serious forms of psychopathology such as alcoholism, anorexia, depression, and personality disorders” (Chang). A tragic example of the effects of perfectionism on lawyers is given by Michele Gazica in her research article Imperfectly perfect: Examining psychosocial safety climate’s influence on the physical and psychological impact of perfectionism in the practice of law. She paraphrases Blatt who writes about Vincent Foster, an American lawyer who committed suicide; “Blatt quotes Vincent Foster as stating that lawyers should “Treat every pleading, every brief, every contract, every letter, every daily task as if [their] career will be judged on it” (p. 1004)” (Gazica). Perfection is subjective. It can be impossible to control the perfectionist ideals you have for yourself. When you feel like you have lost control, it feels like your world is ending, even though you know the clock is still spinning. In relation, Cadieux et al., p.40, found that 24.1% of the Canadian legal professionals who were involved in their study had experienced suicidal thoughts since starting their professional careers (Cadieux et al., p.40).

Full disclosure, I’ve had these thoughts as well. Again, it was in the first couple years of university when I was grappling with perfection and the expectations set on me by me and my surroundings. For me, sleep was the only escape. However, for my boss A.F., sleep can only perpetuate the pitfalls of perfectionism in law in the form of the phantom file. A “Phantom file is the file where you lie half-awake/ half asleep at night stressing about how you’re going to fix it and you either end up getting a very restless sleep, maybe even sleep paralysis where you lie wide awake, and then in the morning you wake up and realize that the file itself does not exist.” A.F. experiences these phantom file dreams every few months. When asked if these dreams affect him, he said that he doesn’t really remember his dreams but that “[He’ll] wake up and go ‘oh shit’ there’s been an error, or something has gone horribly wrong and scramble to fix it up.” Then, he realizes it doesn’t exist and continues his day normally. A.F. acknowledged that these dreams were a product of his stress, but he didn’t think they produced long lasting stress and that they weren’t really related to perfection or productivity.

In general, stress can manifest when you are awake, asleep, conscious, and unconscious (Maté, p.28). Dr. Gabor Maté writes in his book When the Body says No: The Cost of Hidden Stress that “when people describe themselves as being stressed, they usually mean the nervous agitation they experience under excessive demands” (Maté, p.28). This is what A.F. feels when he has these dreams. However, stress is not only characterized by acute nervous agitation but as a “set of objective physiological events in the body involving the brain, the hormonal apparatus, the immune system, and many other organs” (Maté, p.28). Stress not only involves every tissue in your body, but also affects them (Maté, p.33). When A.F. experiences these dreams, they affect his body without his knowledge. Cortisol levels increase when you are stressed (even when you are unconscious and don’t know you are). It can thin your bones which means that an increase of stress can increase your chances of developing osteoporosis (Maté, p.33). Not only that, but cortisol also has an “ulcerating effect on the intestines” (Maté, p.33). This is why chronic stress can lead to gut and intestine issues (Maté, p.33). When I asked my boss A.F. if he thinks his stress has affected his health he said “Oh absolutely, no I don’t think there’s any way that it could not. You know, I think that I probably put weight on, I know that there are various aches and pains that I have you know, and I don’t even want to think what it’s doing to my heart” (A.F). He knows that he’s stressed, he even tells me that he doesn’t think there has been a time since he started his career as a lawyer that he wasn’t stressed. At this point, he’s so used to running on cortisol, that he finds it hard to not do anything/ relax.

The amount of window I can see in the office I use. The entire room is stacked with files with some stacks almost touching the roof.

In regards to what causes the most stress, when P.M. and A.F. were asked about the time that they were feeling the most stressed, their answers related to working hours. P.M. said he was most stressed when “[His] team had been coordinating and advising on a multi-billion-dollar acquisition financing involving some of the largest institutional investors in the world. This required coordination amongst a multitude of stakeholders across the world (from New York, to London, to Japan) to ensure completion. In anticipation of completion, [he] worked from 09:00 am from the day before completion until 10:00 am the following day.” I have pulled all-nighters before to complete school projects, but I can’t imagine the amount of stress P.M. and his team experienced during this acquisition to make it perfect.

In relation, A.F. could not think of a specific time he was extremely stressed but disclosed that he was stressed about how his hours are extending every day and that he’s working more now than he did when he was a young lawyer (A.F.). He gave details about how his perceived stress affects his life outside of work. Constantly working long hours can strain relationships and make one neglect themselves. When people finally get time away from work, they just want to relax. It makes engaging in healthy behaviours, such as exercise, harder. Regarding the education about stress in legal studies, both A.F. and P.M. said that their law school experience taught them nothing about the perfectionism and stress. When A.F. was asked if his seven years of post-secondary education taught him about perfectionist ideals, stress, and the effects of stress, he said “Oh no, because back in the eighties, we were worried more about hair products than we were about things like stress. I think it was still probably a culture where you were supposed to knuckle down and make do and enduring was the norm” (A.F.). When P.M was asked if his three years of law school taught him about stress, he simply answered “No.” (P.M.). This is not a new phenomenon; stress and the effects of stress are ignored in hustle culture. Unfortunately, there has been no other culture in education and work. From my experience, post-secondary education only perpetuates perfectionist ideals given the grading system and the idea that the students who get the highest grades are the ones awarded and considered the best. Nothing else really matters to the education system. In regards to work, you must meet billable hours, please clients, and please the senior employees at the same time, or get fired. There’s no other choice but to hustle in the legal field.

A prospective image of my future.

Even though I’ve learned how to find balance with perfectionism, I’m tired of battling hustle culture. I don’t strive for perfection anymore, because to me, it doesn’t exist, and that realization has given me the best GPA I’ve ever gotten, in my final year of undergrad. While taking four courses per semester and working two jobs, my hair was able to grow back a good amount and I feel better as a whole. To me, practicing law is practicing balance, and at this point, I think it’s something I can do in a healthy manner. I want to help people like the lawyer who helped my grandma, and after gaining first-hand experience working in a law firm and researching the negative aspects of the profession, I think it has better prepared me for a career in law. However, it has also made me realize that I don’t want to work as a full-time lawyer who’s constantly subjected to perfectionist social constructs from other legal professionals and from the general public for an extended period. I know that I will feel bad if I can’t help everyone that comes to me. Also, when I don’t meet my own expectations when I help others, it negatively affects my wellbeing and I feel terrible. I don’t want to hustle for the rest of my life the same way my boss does, and I don’t want my career to potentially have enough power to accelerate a decline in health. Ideally, I’d rather gain experience for a few years and then use the LLB/JD to do pro bono and take on some real estate files on the side.

Works Cited

A.F. (Name Redacted) Interview. By Anita Jheeta. 14 Feb. 2023.

Blatt, S. J. “The destructiveness of perfectionism: Implications for the treatment of depression.” American Psychologist, 50 (12), 1003 – 1020, (1995). https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1037/0003‐066X.50.12.1003

Chang, Edward C. “Perfectionism and Dimensions of Psychological Well-Being in a College Student Sample: A Test of a Stress-Mediation Model.” Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, vol. 25, no. 9, Nov. 2006, pp. 1001–22. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1521/jscp.2006.25.9.1001.

Cadieux, N., Cadieux, J., Gouin, M.-M., Fournier, P.-L., Caya, O., Gingues, M., Pomerleau, M.-L., Morin, E., Camille, A. B., Gahunzire, J. (2022). Research report (preliminary version): Towards a Healthy and Sustainable Practice of Law in Canada. National Study on the Psychological Health Determinants of Legal Professionals in Canada, Phase I (2020-2022). Université de Sherbrooke, Business School. 379 pages.

Gazica, Michele W., et al. “Imperfectly Perfect: Examining Psychosocial Safety Climate’s Influence on the Physical and Psychological Impact of Perfectionism in the Practice of Law.” Behavioral Sciences & the Law, vol. 39, no. 6, Dec. 2021, pp. 741–57. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1002/bsl.2546.

Hewitt, Paul L., and Gordon L. Flett. “Perfectionism in the Self and Social Contexts: Conceptualization, Assessment, and Association with Psychopathology.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 60, no. 3, Mar. 1991, pp. 456–70. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.456.

Maté Gabor. When the Body Says No: The Hidden Cost of Stress, Knopf Canada, 2011, pp. 27–34.

P.M. (Name Redacted) Interview. By Anita Jheeta. 28 Feb. 2023.