Alexandra Platel

At the moment Alexandra is completing a Bachelor’s in Arts at Capilano University with a major in Psychology. As she finds mental health a very relatable and prominent topic in our day and age, in addition to enjoying researching such topics more and more. In the future, Alexandra first wishes to complete her Masters’s in Psychology, perhaps following with a Ph.D. Additionally, she would love to work in the research sector of psychology as opposed to the clinical side. Her main goals for her future is to aid in identifying appropriate tools for individuals who suffer from mental health whilst incarcerated, specifically indigenous peoples, as well as work on future tools to deal with and treat addiction.

When we think of where we find the highest density of mentally ill individuals, one might assume a psychiatric hospital/ mental institution or (if you live in Vancouver) the Downtown Eastside. However, it has been proven that there are disproportionately more mentally ill individuals in correctional facilities, when compared to the rest of the population (Simpson, 2023). Those who are suffering from mental distress have significantly high rates of substance use, depression (1 in 10 individuals), and psychotic illness (1 in 25 individuals) (Jones, 2021). It is estimated that by 2041, the prevalence of mental illness in the Canadian population will have grown by 31%, which is even more frightening in contrast with the projected general population increase of about 26% (Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2023). This highlights once again the importance of fine-tuning the way the community deals with the mentally ill, as they are and continue to be a prominent percentage of our societies. Prisons are some of the largest scale facilities holding mentally ill individuals; however, prisons are not run or designed for the mentally ill, highlighting the immediate need for improvement. It is imperative that mental health systems in correctional facilities must evolve and upgrade their practices and procedures in order to properly care for inmates.

My Personal Connection

Personally, this topic is important to me for various reasons, but the first and most important would be when I became pen pals/friends with an inmate at the B.C. medium-security prison called Matsqui Institution. Once I was approved for in-person visits, I would talk to him about various subjects; one of which was regarding what it was like inside the institution and specifically their mental health and physical health procedures and policies. He would explain to me his point of view of how maladaptive and malfunctioning the mental and physical health system in Canadian prisons are for inmates. Additionally, when visiting I would see how little money was put into the jail; for example, most of their security machines (metal detectors, drug wipe test, etc.) were broken more than 60% of the time for my weekly visits over a one-year period. These visitations allowed me to hear about and see how capital, effort or care is taken to reform their prisoners. Thus, after visiting Matsqui Institution multiple times, my experiences and observations aided me in directly viewing some of the ways in which the mental health of inmates seemed to be (in my opinion) poorly taken care of. Furthermore, after living on East Hastings I noticed how much homelessness, addiction and criminality are ever expanding – notably since Covid. This makes me believe that we must prepare for an increase in mental health issues and therefore prison populations. Moreover, we must call attention to the dire need to improve the way that institutions rehabilitate and care for prisoners (specifically in mental health); thus, I feel motivated to research more on the topic, look more closely at the findings, and identify holes in the research/literacy that may be useful to explore in the future.

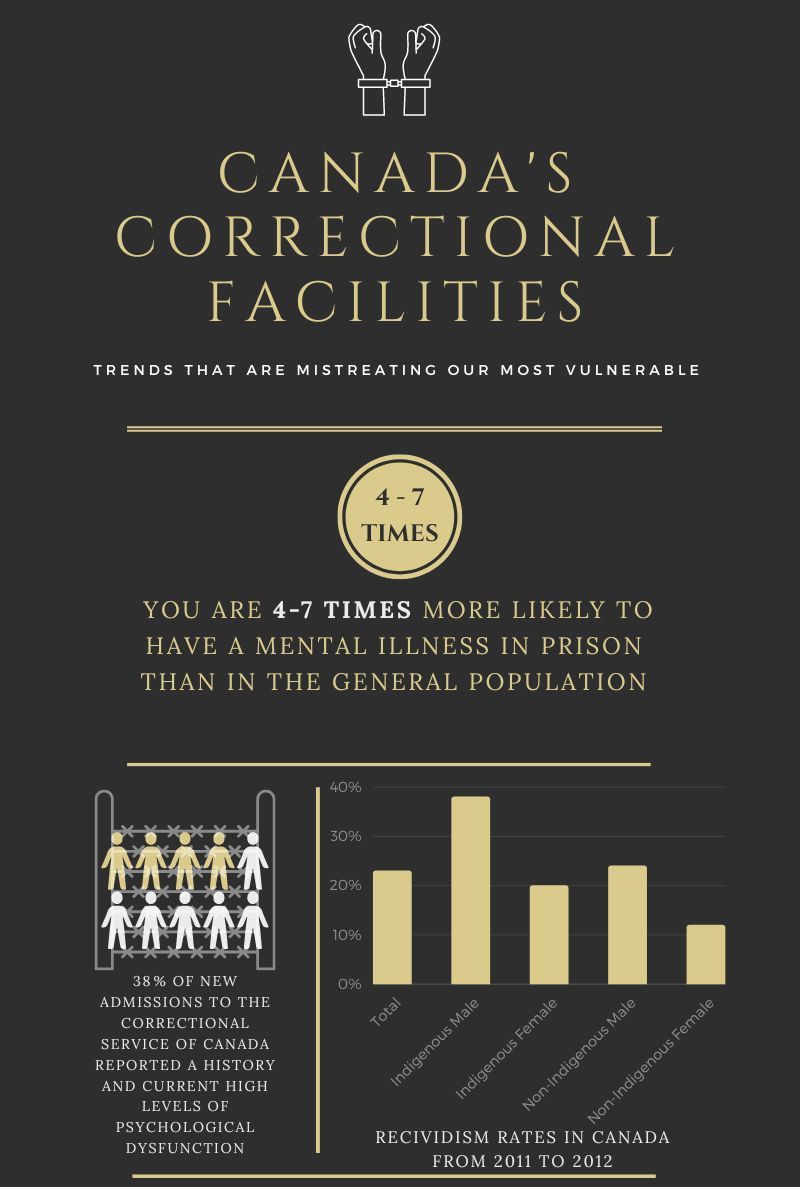

This infographic contains a couple of facts regarding mental health in correctional facilities located in Canada. Such as the much higher likelihood (4-7 times more) that inmates suffer from a mental illness, as opposed to the community. In addition, there is a high prevalence of history or current high levels of psychological issues present in individuals that are being admitted. Furthermore, we can see that recidivism is higher in indigenous people when compared to non-indigenous.

The Darkest Days of Correctional Facilities

In the 1840s, Dorothea Dix, a pioneer of mental health reform, visited and examined the experiences of inmates inside a large number of prisons throughout Europe, the UK and America (Markel, 2020). Subsequently, she provided recommendations to the government based on the research collected (Markel, 2020). Through much effort and countless appeals to Congress, governments acknowledge that “wherever psychiatric care is delivered in a humane and ethical manner, Dix’s name and work continues to thrive” (Markel, 2020). Since Dorothea, there have been advances in the way mental health in the prison system is approched; however, similarly to physical health care, it is essential that professionals are consistently researching and implementing the most effective, progressive and appropriate ways to treat illnesses. Our mental health services must evolve and grow with our society for them to be relevant and useful at this point in time. Another prominent and local researcher, Dr. Amanda Butler of Simon Fraser University and the University of British Columbia has been investigating how to improve health outcomes for people in corrections and how to transform prisons into therapeutic settings (BCMHSUS, 2022).

The debate on the insufficiencies of the mental health system in correctional facilities began not long ago. Until the 1980s, psychological evaluation tools and surveys were still “relatively unsophisticated” and were based on very limited conditions (Colorado College, 2016). Then about thirteen years ago, there was a turning point for the acknowledgement that there must be a change in how these government services are conducted, as the current system was producing recidivism with unresolved mental health issues, due to its misdiagnoses, and undertreated mentally ill population (Colorado College, 2016). Within these thirteen years, we have finally begun to look at mental health treatment somewhat differently. Now, professionals are starting to be able to recognise that treatment approaches depend not only on the type of mental illness present but also on a plethora of other influences such as gender, ethnicity, religion, etc. (Colorado College, 2016). Specifically in Canada, Dr. Serin, a Professor in the Department of Psychology Director and Criminal Justice Decision Making Laboratory of Carleton University, explained that “[in] the 90s – 2000s, more specifically, standardized assessments were done particularly in intake so that it was more likely that the system would identify people with serious mental health concerns and provide care sooner than previously and sooner than acute symptoms who occur” (2023). Through Dr. Serin’s research, he demonstrates that there continues to be some progression in the mental health sector in penitentiaries, although still not substantial enough for the growing population of the mentally ill. Additionally, Dr.Serin explained that the greatest shift (while still not completely adequate) has started in the past five years, where mental health is being regarded in a more humane light than previously (2023). In spite of the fact that there are developments in the way we treat those who are suffering from mental illnesses, there remains much room for research and implementing improvements.

Current Situation

I aimed to generally look into minimum to maximum correctional facilities/systems in North America, but most specifically in Canada. Furthermore, we are experiencing a fairly unique time period, as we are slowly coming out of worldwide public distancing mandates due to the COVID-19 virus. Social isolation and social distancing disturbed the natural and mentally healthy interaction between people. This virus has put heightened strain on and exacerbated numerous mental disorders, therefore making the conversation of mental health of even greater importance. In addition to this, during the last five years, there has been inceased scrutiny on correctional systems and their employees. As well, when looking at the Canadian penitentiary systems, one may notice that although Canadians are a fairly progressive society, our penitentiaries are far from progressive (compare to Finland, for example).

Here is a photograph taken at Vancouver’s Downtown Community Court on Main St. and Gore Ave. On the BC government website they porcelain that this court is a “first of its kind … A high number of offenders in downtown Vancouver have health and social problems, including alcoholism, drug addiction, mental illness, homelessness and poverty. The court takes a problem-solving approach to address offenders’ needs and circumstances and the underlying causes of their criminal behaviour.” (BCGov., 2023), although this has yet to be proven.

Context affects the issue of criminalization of mental illness when the overflow or large portion of those committing crimes are those with mental illness. This points toward a gap in mental health services and treatment options available to the community/public. In addition to this, if the government does not have the resources and space to hold the amount of mentally ill people, it may cause over-incarceration in institutions that already do not have enough space to hold those with more severe cases and who require more intense treatments. Another context-dependent impact on individuals’ mental health is negative large societal events, such as the opioid crisis, inflation, natural disaster, war or the COVID-19 pandemic. An additional aspect of context, regarding how jails are run is the quality of inter-employee relationships. In other words, how employees of different seniority levels communicate and interact with each other, as well as the amount of respect shown.

Literature Review

Mckendy and Ricciardelli demonstrate and measure the well-being and experiences of correctional workers in Manitoba or Saskatchewan through the use of open-ended survey questions. While highlighting a significant disconnect between those working on the front lines and those working in senior management positions, McKendy and Ricciardelli point to this as a cause of negative impacts on their communication and therefore resulting in feelings of mistrust, frustration, lack of support, lack of safety, and more. The authors note that the effect of these adverse feelings and experiences caused by working in such correctional facilities may in turn, unfortunately, trickle down to affecting those who are under their supervision and in their custody (McKendy & Ricciardelli, 2022).

Kelley, Edens, and Douglas utilized several instruments, such as the Personality Assessment Screener (PAS), Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI), Behavioural Inhibition System (BIS) Scale, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale—Version 11 (BIS11), Child Abuse and Trauma Scale (CATS), Dissociative Experiences Scale—Version II (DESII), Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI), Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II), and the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) in order to measure inmates mental health (and symptoms). The results of the study illustrate that PAS may be one of the best assessment tools for inmates regarding their mental health, noting that it includes sections pertaining specifically to illegal activity, resulting in more accurate PAS results. Furthermore, they highlight that PAS would be a viable means of assessing whether an inmate’s psychological difficulties/mental health requires additional assistance (Kelley et al., 2018).

Researchers, Brown, Hirdes and Fries, employed the Resident Assessment Instrument – Mental Health (RAI-MH) between May 2005 – September 2007, in order to assess the mental health status and to evaluate the prevalence of negative mental health symptoms present in inmates. Using a volunteer sample of 522 inmates, the results demonstrate that more than 30% of those with two or more severe symptoms may be classified as “high risk/immediate need” on the RAI-MH. Additionally, there is a substantially higher percentage of severe symptoms in female and Indigenous inmates who generally have lesser access to the mental health services than they might require. Moreover, this research points to the divergence between the financial resources available for such sectors, the treatment programs offered, and the expertise that is compulsory for treating such severe mental health symptoms and disorders. Finally, the study suggests that in the future it would be beneficial to dive deeper into the identification of specific strategies that may help tackle the needs of females, Indigenous and other distinctive groups of inmates that are disproportionately higher in people who have severe mental health symptoms (Brown et al., 2015).

In this picture, I was able to take near Vancouver’s notorious East Hasting St (and Main St.), which is home to the poorest area code of Canada and with the highest population of homelessness and drug addiction. Many of these individuals are not unfamiliar with correctional facilities and engage in a cyclical system of going between prison and the streets until inevitable death. The man specifically depicted in this picture highlights the desperation in addiction and mental health of which has deteriorated to a decrepit state.

Identifying Problems and Finding Solutions

Today, Canadian jails have the highest concentration of mentally ill individuals when compared to the general population (Simpson, 2023). This may be due to individuals with mental illness having a greater probability of committing a crime as well as recidivism (Ghiasi et al., 2023). Thus, increases in mentally ill individuals in a population would potentially result in increases in incarceration and recidivism. In order to lower the amount of (mentally ill) individuals incarcerated and to decrease the amount of overcrowding in Canadian prisons, our society – governments, institutions, and health professionals – must target effective treatments for mental disorders that may be conducted within a prison setting. Additionally, it has been found that “…mental health conditions are among the most common conditions affecting federal inmates, including anxiety and mood disorders (12)”, thus highlighting the prominence of such issues in Canadian jails (Lee et al., 2021).

The most widely used approach to mental health in penitentiaries is generally a cookie-cutter/one size fits all type method, which is proving to be ineffective for the several disorders that inmates might be dealing with. In an interview with a former inmate, Nelson Butler, when asked what the most successful modalities of rehabilitating prisoners would be, he pointed out, “The trick to rehabilitation is an individual approach where the offender has his/her particular issues identified, and then they are directed towards issue-specific programs that address that person’s own needs” (2015). Mr. Butler goes on to explain how the various programs, that were available at the correctional facility in which he was held, were not suited to him and thus he did not benefit from them (Butler, 2015). Therefore, instead of wasting tax dollars on a system that is disadvantageous to those who it is supposedly designed for, programs and treatments need to be modified for the individuals in the correctional system whom the judicial system is trying to be rehabilitate. An example of a more rounded program that offers better-targeted assistance is the Tupiq Program which was designed for Inuit Sex Offenders; the offenders are provided “a correctional intervention that targets these criminogenic areas in one integrated program and provides ongoing maintenance for the graduates of the program closer to Inuit communities and to the resources and services that form a key component…” (Stewart et al., 2014). A specialized program for Inuit sexual offenders is especially important when we look at their high rates of suicide, brain injury and experiencing traumatic events in their developmental years, as well as low rates of education and employment (Stewart et al., 2014).

In addition, Thomas C. O’Bryant identified another facet of providing unsuitable mental health care which focused on how misdiagnosis or mistreatment may be dispensed wrongly (Felner, 2023). Giving the exact diagnosis is not easy for psychologists and psychiatrists, as various labels have similar symptoms – if looking at anxiety, ADHD, borderline personality disorder, addiction, etc. – traits overlap or psychiatric comorbidity may be present. Additionally, there is the financial aspect and problem, as therapeutic and medicinal treatments, diagnoses tools, mental health facilities, staff, and more are costly and can take months or years of sessions to help break a cycle or find a treatment and personal tools/techniques that work for someone who is suffering mentally. Erroneous diagnosis and treatment may easily result in the prescription of inappropriate psychotropic medications, which in turn may drastically impair the individual’s ability to function (Felner, 2023).

This picture is here to highlight the importance but also sometimes strong reliance we have on medication. Additionally, the prevalence of misprescribed medication may be counteractive to what the patient is taking the medication for. Which can all have adverse and long-lasting results. Therefore, it is imperative to have rigorously tested treatment options for all forms of mental disorders.

Legally, the correctional system has the responsibility to deliver the equivalent and appropriate health care (which includes mental health and harm reduction) as is available to the general public. Nevertheless, our penitentiaries rarely have the chance to operate in this way due to a lack of resources (notably mental health resources), inadequate staffing, and a significantly high number of inmates in need of such care (Lee et al., 2021). The results of one study, which was conducted on the topic of inmates’ satisfaction overall with the mental health services provided by the jail, emphasized that a least 44% were unsatisfied with the current mental health assistance (Lee et al., 2021). To further call attention to the dysfunctionality of these mental health services are statistics from the Office of the Correctional Investigator (OCI) of Canada in 2018/2019, where it was shown that 20% of incidents that involved the use of force took place in treatment centers for inmates with mental illness. Given the numbers from earlier, this seems like a high rate of use of force on a population that responds poorly to such tactics. To additionally demonstrate and solidify the inefficiency of our correctional system, the OCI found that one in ten of such incidents were “deemed [to be] unnecessary and/or inappropriate” (OCI, 2019). All these statistics indicate that our system is seriously flawed and clearly in need of change. Forbye, Dr. Butler highlights an important aspect of correctional facilities, which is actively trying to rehabilitate inmates, as she states, “Of course overall we want to prevent people with mental health and substance use disorders from criminal offending, but if they end up in corrections, we should capitalize on that opportunity by providing treatment and resources to achieve the dual objectives of reducing the risk of criminal offending and helping people to get well” (2022). This brings to attention the missed opportunity to properly and effectively treat mentally ill individuals whilst lowering recidivism rates and contributing to society.

Another hurdle for correctional facilities is the issue of overcrowding. There are several reasons that have led to overflowing Canadian jails, the main six being: “(1) the country’s excessive reliance on incarceration, which is regarded as the best means of ensuring public protection; (2) dramatic increases in the number of inmates, in the numbers designated as dangerous, and numbers serving long and life sentences; (3) increasing public intolerance and punitiveness; (4) lack of public support for measures other than incarceration; (5) lack of effective community-based programs; and (6) releasing authorities have become overly cautious” (Canadian Criminal Justice Association, 1998). Having the government rely heavily on incarceration rather than provide psychiatric or community-based treatment is a prime example of how malfunctioning this system is. The cost of detaining an inmate in federal custody for 30 days would be the same as undergoing (the cheapest) treatment at a psychiatric center (Vanable, 2021). Therefore, our tax money is misused – by imprisoning mentally ill individuals – not only through how much they cost to keep in jail compared to undergoing proper treatment but through societal damages (i.e. theft, injury to others, property damage, hospital stays, etc.) caused by untreated mental illness, as well as that there is a chance of reoffending, thus resulting in a more extensive stay in jail.

However, since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Serin pointed out that incarceration numbers have decreased slightly (mainly due to social distancing mandates), as judges attempt to limit the number of individuals going into the system (2023). This may still not be very beneficial, as those who are mentally ill are simply returned to the environment that drove them to commit the crime, only temporarily decreasing incarcerations until the individuals inevitably re-offend. Moreover, Crime Statistics in BC in 2021 (mid-pandemic) revealed an increase of “626 more violent offences reported by police in BC in 2021, with the largest increases being homicide (25), extortion (208) and sexual offences (+748)” (Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General, 2022). At this point, one can only question its link to mental health during this pandemic period.

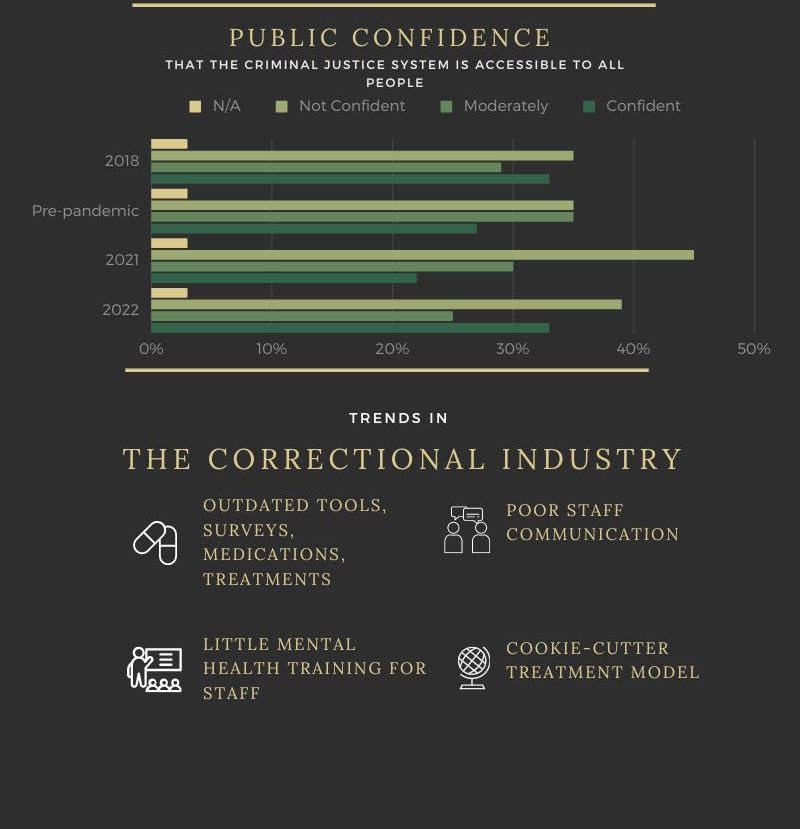

We can see a chart below this information that demonstrates how especially since the pandemic how rates of public confidence felt has diminished when compared to previously. And finally, there’s a couple of correctional trends are highlighted such as the use of outdated tools, such as mental health identifying surveys, medication and treatment strategies. Some other trends include having very little mental health-specific training for corrections staff, having poor communication between various staff seniority levels, as well as utilizing a cookie-cutter/general treatment model for all inmates regardless of background, disorders, etc.

Therefore, incarcerations could be predicted to increase and potentially be worse than before, as a repercussion of the pandemic’s increases in mental illness, notably addiction, which are two of the main predictors of criminal activity (CCSA, 2023) (CMHA, 2013). In our interview, Dr. Serin explained that he believes that it is essential to implement specialized and accurate testing to identify mental illnesses (in need of treatment) early on in the judicial process, in order to deem whether this individual should be sent to a mental institution or a correctional facility (2023). In other words, a system needs to be created to firstly limit the number of mentally ill patients that are admitted into jails, and furthermore prevent the exacerbation that jails may cause to untreated or uncontrolled disorders. The focus needs to change from punitive based to treatment-oriented and after to prevention of further criminal acts.

As briefly mentioned previously, addiction is a prominent aspect present in our penitentiary systems, as “it is estimated that at least 10 percent of inmates meet the criteria for fetal alcohol syndrome, 80 percent have substance abuse issues when incarcerated” (Ling, 2021). Encompassing addiction when speaking about mental health is important. Firstly, it is prominently tied to the way a person acts, yet does not define a person; similarly, if someone has a major depressive disorder, it may impact the way a person conducts themselves but does not define their personality. In fact, addiction is included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) as a disorder (Substance Use Disorder). Furthermore, substance use disorders result in several cognitive impairments, such as social, academic, occupational, as well as physical health consequences, comparably to other mental health disorders (Jahan & Burgess, 2022). In a study conducted by Lynn Stewart and Geoff Wilton for the research report on the Correctional Services of Canada, it was “ revealed that combinations of disorders with substance abuse disorders and personality disorders were the most frequent. In fact, 66% of offenders with any type of current substance abuse disorder had a personality disorder as well. Likewise, 68% of offenders with a personality disorder were found to have at least one current alcohol or drug abuse or dependence disorder” (2017). Hence, one can see in our prisons the strong prevalence of substance abuse in combination with a personality disorder. With this strong comorbidity, steps should be taken to identify either disorder at the earliest possible stage, in order to prevent further progression of such disorder, or to prevent such common comorbidities to form.

It is imperative to work towards identifying an appropriate system that helps the mentally ill receive treatment as well as reduces rates of reoffence. Not only do such adjustments keep our communities safe and healthy, but they help those in desperate need. Even though there is a large portion of inmates who suffer from mental illnesses, and there are very limited resources available for those with mental illness, we are able to find considerable, new opportunities to improve the way we run jails (such as adopting progressive methods like Finlands). Numerous avenues would benefit from research in the future, such as improved mental health prevention, very specialized mental health treatments and tools (ie. surveys, etc.), enhanced officer training, increased number of specially trained personnel, and less hierarchical-based employee systems. The consequences for inmates and our society, if we do not rectify the insufficiencies of our mental health system of our correctional facilities, are substantial; as we risk: imprisoning more and more of our most vulnerable who are far rather in need of treatment, exacerbating their symptoms, putting them in danger, misdiagnosing and mistreating.

References

BC Mental Health and Substance Use Services. (2022). Improving health outcomes for people in corrections: Researching the transformation of prisons into therapeutic settings. BCMHSUS. http://www.bcmhsus.ca/about/news-stories/stories/research-aims-to-improve-health-outcomes-in-corrections

Brown, G. P., Hirdes, J. P., & Fries, B. E. (2015). Measuring the prevalence of current, severe symptoms of mental health problems in a Canadian correctional population: Implications for delivery of mental health services for inmates. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 59(1), 27–50. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1177/0306624X13507040

Bonta, J., (2013). Risk and Mentally Disordered Offenders. Public Safety Canada Corrections Research. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/rsk-mntl-ffndr/index-en.aspx

Butler, N. (2015). What are the most successful methods of rehabilitating prisoners. Corrections 1 By Lexipol. https://www.corrections1.com/re-entry-and-recidivism/articles/what-are-the-most-successful-methods-of-rehabilitating-prisoners-HybDwaodwpUIf7mV/

Canadian Center on Substance Use and Addiction. (2023). Mental Health and Substance Use During COVID-19. https://www.ccsa.ca/mental-health-and-substance-use-during-covid-19

Canadian Criminal Justice Association. (1998). Prison Overcrowding and the Reintegration of Offenders. https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/prison-overcrowding-and-reintegration-offenders#:~:text=Reasons%20why%20Canadian%20prisons%20are,and%20life%20sentences%3B%20(3)

Canadian Mental Health Association. (2013). Violence, Mental Illness and Substance Use. Here to Help British Columbia. https://www.heretohelp.bc.ca/infosheet/violence-mental-illness-and-substance-use

Colorado College. (2016). Criminalization of Mental Illness. Past, Present, Prison. https://sites.coloradocollege.edu/hip/mentally-ill-and-the-penal-system/

Ghiasi, N., Azhar, Y., Singh, J., (2023). Psychiatric Illness And Criminality. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537064/#:~:text=Certain%20psychiatric%20conditions%20do%20increase,or%20have%20long%2Dstanding%20paranoia.

Jahan, AR., Burgess, DM. (2022). Substance Use Disorder. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570642/.

Jones, R. (2021). Preventing the reincarceration of prisoners with mental illness. Psychiatry University of Toronto. https://psychiatry.utoronto.ca/news/preventing-reincarceration-prisoners-mental-illness#:~:text=However%2C%20rates%20of%20mental%20illness,have%20a%20serious%20mental%20illness.

Kelley, S. E., Edens, J. F., & Douglas, K. S. (2018). Concurrent validity of the personality assessment screener in a large sample of offenders. Law and Human Behavior, 42(2), 156–166. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1037/lhb0000276.supp(Supplemental)

Lee, A., Ross, A., Saad, M. (2021). Health Care Reform in Canadian Corrections Facilities. Ontario Medical Students Association. https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/related_material/A%20Corrections%20Quandary.pdf

Ling, J., (2021). Houses of hate: How Canada’s prison system is broken. Maclean’s. https://macleans.ca/news/canada/houses-of-hate-how-canadas-prison-system-is-broken/#:~:text=Our%20prison%20system%20is%20warehousing,cent%20have%20antisocial%20personality%20disorders.

McKendy, L., & Ricciardelli, R. (2022). The forces that divide: Understanding tension and unity among provincial correctional workers in Canada. Criminal Justice Studies: A Critical Journal of Crime, Law & Society, 35(2), 200–218. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1080/1478601X.2022.2061479

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2010). Making the Case for Investing in Mental Health in Canada. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/drupal/2016-06/Investing_in_Mental_Health_FINAL_Version_ENG.pdf[Text Wrapping Break]Markel, H. (2020). Dorothea Dix’s tireless fight to end inhumane treatment for mental health patients. Public Broadcast Station News Hour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/dorothea-dixs-tireless-fight-to-end-inhumane-treatment-for-mental-health-patients

Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General. (2022). Crime Statistics in British Columbia, 2021. Policing and Security Branch. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/law-crime-and-justice/criminal-justice/police/publications/statistics/bc-crime-statistics-2021.pdf

Rossler, W. (2016). The stigma of mental disorders. National Library of Medicine. ttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5007563/#:~:text=During%20the%20Middle%20Ages%2C%20mental,the%20walls%20or%20their%20beds.

Stewart, L., Hamilton, E., Wilton, G. (2014). The Effectiveness of the Tupiq Program for Inuit Sex Offenders. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262978442_The_Effectiveness_of_the_Tupiq_Program_for_Inuit_Sex_Offenders.

Simpson, S. (2023). Mental Illness and the Prison System. Center for Addiction and Mental Health. https://www.camh.ca/en/camh-news-and-stories/mental-illness-and-the-prison-system

Vanable, J. (2021). The Cost of Criminalizing Serious Mental Illness. National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/Blogs/NAMI-Blog/March-2021/The-Cost-of-Criminalizing-Serious-Mental-Illness

Zinger, I., (2019). 2018-2019 Annual Report. Office of the Correctional Investigator. https://www.oci-bec.gc.ca/cnt/rpt/pdf/annrpt/annrpt20182019-eng.pdf