Laine Tadey

Laine Tadey is a spring 2022 graduate from Capilano University’s Interdisciplinary Studies program. She has recently been accepted into Simon Fraser University’s Professional Development Program to pursue a career as an elementary school teacher. She hopes to use her experience growing up with social media to bridge the gap between those that are growing up in the age of social media, and those who have not.

Personal Narrative

I am one of the first generations, an experimental generation, to grow up with the presence of social media in the formative years of development. Not only did I have to navigate adolescence through face-to-face interactions, I also had to navigate it online. Social media was the ideal space to exacerbate my anxious and perfectionist characteristics, while confirming that my appearance was my top quality. I would get significantly more likes and comments if I posted a selfie, and if I was in a bikini, boys felt that was an invitation to send me a direct message. When I got likes, I felt a rush of confidence, and when I did not, I felt discouraged. I compared myself to others, ignored my accomplishments and believed by self-worth was determined by others. I let Instagram define my life.

In my last year of high school, I was voted “class heartthrob.” It was not a surprise as I had been anxious about it for weeks. My friends would come up to me during the voting process telling me, “So and so, just told me they voted for you, everyone is voting for you.” While knowing this filled me with excitement, mostly I was unsettled. Was that all my classmates thought of me –my face, my body –all that mattered? Is this how the world saw me? Since social media told me that this was the case, why would I believe it to be different now? My appearance was my defining quality, my accomplishments, my personality, and my aspirations didn’t matter. What mattered was what I looked like.

The education system failed to prepare me for this aspect of adolescence. No one helped me navigate this social world that emphasized appearance and likes as a signal of self-worth. No one taught me to think critically about the media I was consuming and that there was an algorithm feeding me specific posts. No one showed me how to create content that showcased my accomplishments and aspirations. No one warned me about the impact of upward social comparison, body dysmorphia, and unrealistic beauty standards on my mental health. My teachers should have recognized that I lacked the skills and confidence to resist the pressures placed upon me by this online world. Instead, I struggled to figure it out on my own; to question my self-worth every time I exited Instagram and wonder if I was good enough. Why would I not? No one had taught me differently.

Introduction

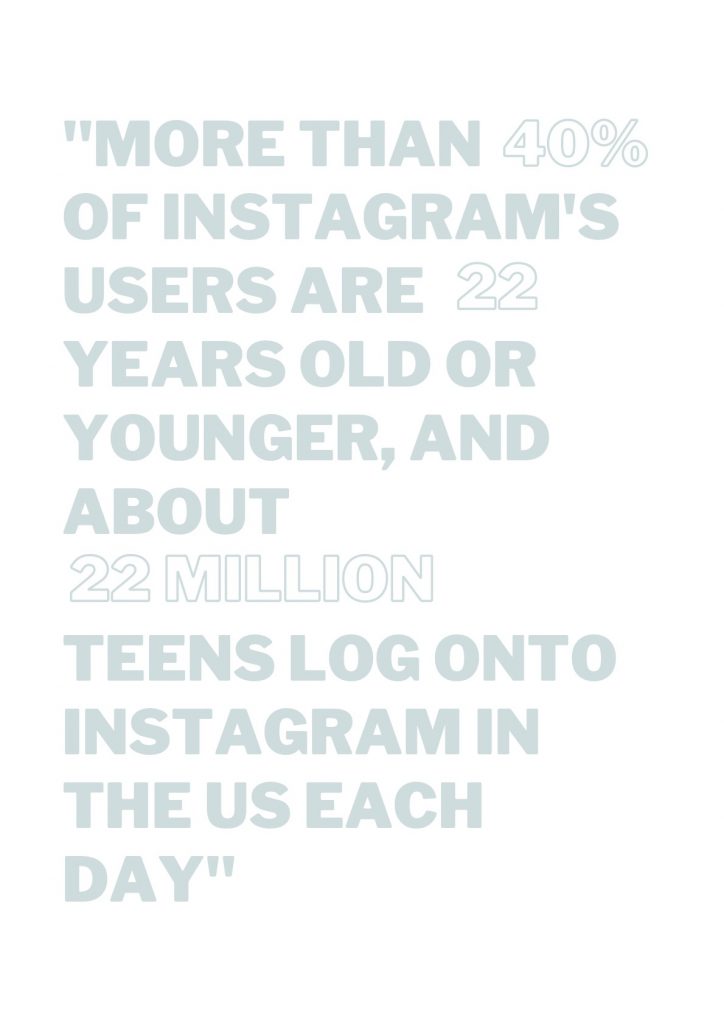

The Washington Post reports that one-third of children aged 7-9 use social media (Searing, 2021), and Statistics Canada reports regular use of social media platforms by 9 in 10 Canadians aged 15-34 (Schimmele, Fonberg, & Schellenberg, 2021). Facebook is pushing to develop “Instagram Kids” despite opposition from parents and lawmakers, and the company has plans to create a Metaverse (Mac & Silvermann). These plans are continuing despite leaked documents that revealed Facebook’s awareness of Instagram’s toxic effect on teen girls’ body image and mental health (Wells, Horwitz, & Seetharaman, 2021). In addition, the Covid-19 pandemic increased participation on social media platforms by75% for Canadians over 15 years of age (Bilodeau, Kehler, & Minnema, 2021). It is evident that social media is not going away, therefore now more than ever is the time to be proactive in developing young people’s digital literacy. This is critical as academic and popular articles report that globally, individuals struggle with mental health issues exacerbated by social media use (Vries, Peter, Graff, & Nikken, 2016; Twigg, Duncan, & Weich, 2020; Yang, Wang, & Yang, 2020; Schimmele et al., 2021).This is particularly concerning for young people because they have high participation on social media platforms, yet they do not fully understand the implications of their online actions (Media Smarts A, nd).

Among those concerned is Mrs. B, a grade 6/7 teacher in North Vancouver, who recognizes the importance of developing digital literacy among her students. She notes that her students are in a critical time of experimentation to formulate their identities, and that “…their brains aren’t fully functioning” all the time. With social media, she says, “…there is this sort of Big Brother always looking out” in which young people are growing up in a world where their online choices are permanent. In addition, she recognizes that young people are inundated with visual content that requires the same analysis as text. Through our conversation and my research, the importance of developing digital literacy education among young people became evident. However, systemic barriers inhibit the implementation of digital literacy in the classroom. These include insufficient digital literacy knowledge of educators, inadequate support for the implementation of digital literacy in the classroom, and that digital literacy is optional for educators to teach and learn about. To overcome these barriers, I argue that the education system must equip educators with formal digital literacy training in teacher education programs, must utilize school personnel to assist current educators, and must adopt outside programs to support in-class digital literacy learning.

What is Digital Literacy?

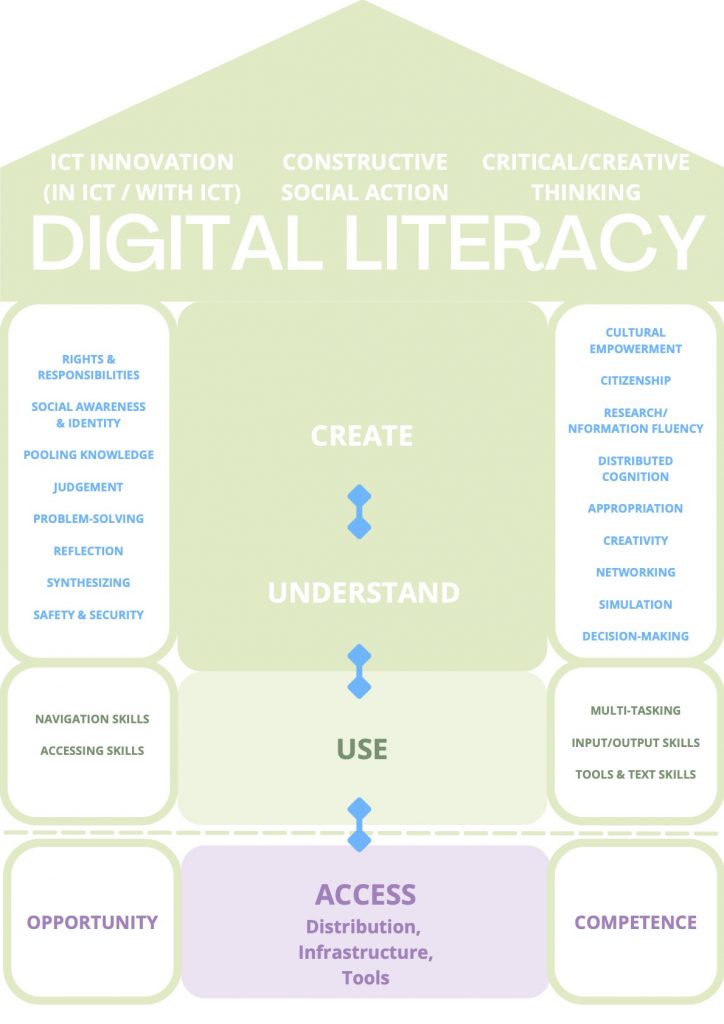

Digital literacy focuses on “…enabling youth to participate in digital media in wise, safe and ethical ways” (Media Smarts B, n.d., n.p.). It draws on media literacy which involves teaching young people to be critical consumers of media. However, the nature of social spaces as collaborative means that young people need to also be taught how to participate in the social world (Media Smarts B, n.d.). Digital literacy does this by educating youth through three fundamental categories: use, understanding, and create (Media Smarts A, n.d.). This ranges from developing basic technical skills, understanding how to “…comprehend, contextualize, and critically evaluate digital media,” and by understanding how to create content for various online contexts (Media Smarts A, n.d., n.p.). Understanding how to participate in the social world through these lenses further gives young people the tools to understand how content may affect behaviours and perceptions (Media Smarts A, n.d.). This aspect of digital literacy relates directly to mitigating the adverse effects of social media on young people by focusing on mental health.

Literature Review

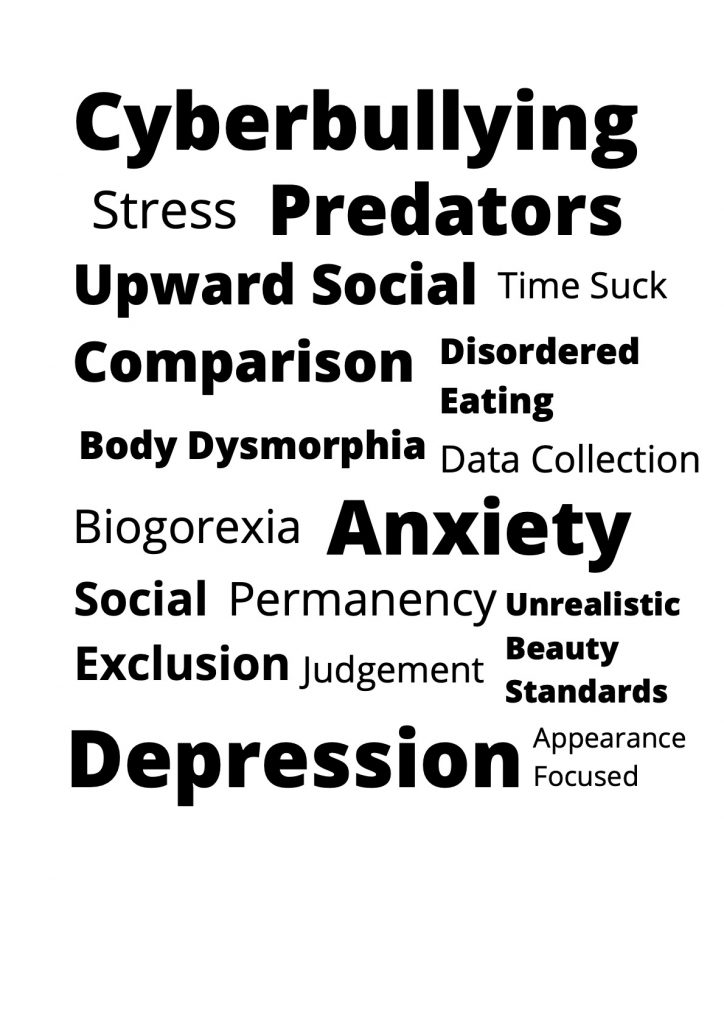

Mental health issues linked to social media use are especially worrisome for young girls. During this stage of development, they are vulnerable due to unwanted body changes, experience appearance focused popularity, and are sensitive to peer feedback (Vries et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2020). “Highly visual” platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat, and Tik Tok can emphasize and encourage the internalization of unrealistic beauty standards which young girls feel pressure to uphold(Yang et al., 2020). As a result, those who do not conform to these standards are left feeling insecure and unsatisfied with their physical appearance. If individuals lack the skillset or maturity to resist ideals, this may escalate anxiety and depression and can result in developing an eating disorder (Yang et al., 2020).

It is the constant exposure to misleading and unrealistic content that often leads to upward social comparison: where individuals compare themselves to those they deem to be better (Vogel et al., 2014). As we scroll, we are unconsciously and consciously critiquing every aspect of our lives. We forget that images are cropped, photo-shopped, filtered, and staged, and fail to consider what is left off the screen (Holland & Tiggemann, 2016). Experiences on social media therefore place unrealistic pressures on young people to perform in all aspects of their lives (Hjetland et al., 2021). They must do well in school, have an engaging social life, and look a certain way. The Wall Street Journal compares social media to the high-school cafeteria where teens “…size each other up, brag, and bully” to convey social status (Wells et al., 2021). However, social media is not left at school. As a result, it opens young people up to a new world of social anxieties and pressures (Hawgood, 2022). Without the skills to understand how to engage with online platforms and content, individuals can be left feeling like they are never enough.

While the literature emphasizes social media’s adverse effects on girls, boys are as affected. A recent New York Times article examines the growing concern of “bigorexia,” a “…form of muscle dysmorphia” in males (Hawgood, 2022, n.p.). Hawgood (2022) reports that boys feel pressure to uphold a hyper masculine image which can result in extreme dieting, disordered eating, and the use of steroids and supplements to achieve a desired physical appearance. The article warns that as early as elementary school, boys may feel pressure to emulate those they see online (Hawgood, 2022). Though the media tends to focus on social media’s effect on females, every individual has a different experience with social platforms. Therefore, people of all genders, ethnicities, sexualities, ages, and abilities would benefit from digital literacy.

Among the academic community there have been calls for educational intervention to mitigate the adverse effects of social media. Hjetland et al. (2021) recognize the centrality of social media to the lives of adolescents and the need to adapt lessons to guide students. Vries at al. (2016) point to the need for intervention with a focus on“…adolescents who report high levels of body dissatisfaction” (p. 222). Yang et al. (2020) stress the importance of school and community-based interventions with a focus on “…holistic, wellbeing-centered utilization of social media and safety risks” (p.14). Other findings emphasize the importance of improved digital literacy not just to mitigate adverse effects, but to give students the tools to take advantage of the positive effects of social media (O’Reilly, 2020). It is with this in mind that digital literacy programs should be used by the education system to mitigate the negative effects of social media while also harnessing its power.

Intervention techniques aimed at mitigating the effects of social media show positive results. Yamamiya et al. (2005) found that only a five-minute exposure to “ideal” images resulted in decreased body satisfaction. However, when photos were followed by a short media-literacy lesson the internalization of ideals and body dissatisfaction decreased (Yamamiya et al., 2005). Similarly, Posavac, Posavac, & Weigel (2001)found that three intervention techniques reduced social comparisons and minimized the effects of body ideals on women. In addition, a two-year follow up study revealed that a program focusing on increasing knowledge about healthy body relationships among9to 11-year-oldstudentsresulted in better body esteem and less dieting (Smolak & Levine, 2001).These findings showcase that critically engaging with media reduces its potential negative effect. Findings also support the use of proactive methods to provide young people with the tools to resist ideals before mental health issues emerge. This is one area that digital literacy could prove to be beneficial.

Implementing Digital Literacy in the Classroom Despite the knowledge that education is key in mitigating adverse effects of social media, there are barriers preventing educators from providing sufficient support. Mrs. B recognizes that educators “…can only do so much within the walls of the classroom.” Once the bell rings, students are left to their own devices and educators are often left unaware of what happens in the social world. Adding to this limitation is the generational gap that exists between young people, and the adults who have little understanding of the importance the online world plays in young people’s lives (Hjetland et al., 2021).As a result, there can be a disconnect between what support students desire versus what adults believe is needed (O’Reilly, 2020).However, a good educator recognizes the necessity in providing students with digital literacy to allow knowledge and critical thinking skills to follow students out of the classroom.

Increasing this divide is that schools have limited resources to integrate knowledge into the classroom (Hjetland et al., 2021).In British Columbia, digital literacy is integrated into the Applied Design, Skills, and Technologies(ADST) curriculum. However, educators have a choice whether they teach digital literacy or choose to focus on other modules in the ADST curriculum (BC Government, n.d.). Mrs. B believes that what influences this choice is an educator’s confidence in the subject area.“ Teachers teach what they know,” she says, and if they lack training in digital literacy, they are likely to stay away from it. In her own case she recognizes that she is not an expert, and while she can draw on personal experiences and resources to support students, sometimes it can be overwhelming.

Further, teacher education in digital literacy is inconsistent in Mrs. B’s district. There have been workshops during professional development days but attendance is not required. For those that do attend, workshops can leave educators feeling inspired, but barriers prevent them from implementing changes. Even though resources are provided by the school district in some capacity, a lot of the resources Mrs. Buses are what she has found through personal research. Therefore, she must make time to research, learn, and prepare lessons.“ It is very difficult to implement” she says, “because there are so many other demands on your time an energy.” While educators may be keen to teach digital literacy, lacking the skillset or time to do so is a great barrier. Without support from the education system, educators face enormous pressures which may result in them choosing to forgo teaching it. It is not enough to provide educators with a link to resources and a one-off workshop, a systemic change is needed to ensure educators have sufficient support to teach digital literacy.

Butler (2020) believes that leaving educators to their own devices is one of the main downfalls of implementing media literacy programs in the classroom. In one of her studies, she found that“ Teachers were often resistant to include media literacy because of their lack of familiarity with the subject, their limited time to add new things to their curricular scope and sequence, and their day-to-day class demands” (Butler, 2020, p. 74). To implement programs educators must be willing to learn, give up their time, and adapt their schedules to meet new demands. While it is up to students to be responsible users and consumers, the ownership lies with educators to ensure students are well informed. To develop students’ digital literacy, Butler (2020) argues that the first step is through formal education training, particularly for prospective teachers. By arming educators with“…greater expertise and more adaptable tools” they can better support students in their classrooms (Butler, 2020, p. 88). This would mitigate any apprehension felt by educators to include digital literacy lessons while encouraging young people to engage with platforms responsibly“…beyond the walls of the classroom”(Butler, 2020, p. 93).As young people are supported by their teachers, they will gain the skillset to engage with platforms in a responsible way which will hopefully spread into other aspects of their lives.

For current teachers, Mrs. B believes that re-envisioning the roles of other school personnel can help with the implementation of digital literacy in the classroom. She sees this as a chance to utilize the school counsellor whose role is to typically to do“…triage and help support students who have been flagged.” Instead, they could come in as a co-teacher to deliver programs and be “…an expert for all students to access.” Not only would this benefit students, but educators can learn by “osmosis,” particularly when dealing with the role of social media and mental health. By reimagining roles, intervention strategies can flip from being reactive to proactive, with the latter being more impactful in mitigating adverse effects of social media (Posvac et al., 2001; Smolak & Levine, 2001; Yamamiya et al., 2005).

In addition to the school counsellor, librarians have been recognized for their role in being an essential collaborator in the implement of media literacy in the classroom (De Abreu, 2019; Merga, 2019; Butler, 2020). Merga (2019) describes that “The educative role of the teacher librarian within a school includes fostering the literacy and literature capabilities of its students” (p. 91). They are media experts that can act in collaboration with teachers to deconstruct, evaluate, and analyse media (De Arbreu, 2019).It is with this in mind that the expertise of the librarian, as critical evaluators of all forms of media, can be harnessed to teach digital literacy. Merga (2019) also argues that collaboration among school staff can be extremely beneficial for student achievement. Re-imagining how to implement digital literacy in the 10education system is therefore not only beneficial in arming students with the tools to participate in social spaces, but in fostering stronger connections within the school community.

Digital Literacy and Outside Programs

Digital literacy can also be integrated into classrooms with the support of outside programs. Mrs. B recognizes the importance of these programs as they can sometimes “…lead to a student sharing something personal.” As a result, educators can gain insight into where more support is needed and for whom. In addition, utilizing a variety of workshops allows for coverage of many topics and can provide educators with tools to support students. Some of the programs utilized by Mrs. B include:

-Second Step which is a teacher led program focusing on social-emotional learning by providing resources and training for educators. They provide targeted age-appropriate lessons.

-Jesse Miller, who educates young people about social media and the internet through keynote presentations.

-Safe Teen which focuses on violence prevention through empowering young people. The elementary program is recommended for grade seven students and is delivered through a three-hour workshop.

-Children of the Street which prevents the sexual exploitation of young people through prevention, intervention, and support. One of their workshops, Safer Space is dedicated to social media safety.

While utilizing outside support is attractive, Mrs. B believes that the success of a program relies on its ability to be user friendly, age-appropriate, create a safe space, and be consistent. She applauds Second Step for being “…realistic, achievable, and easy to implement” because she is provided with resources from experts, and it does not take time away from her other demands. Second Step also provides targeted grade level lessons that get more complex as students age. Students starting in kindergarten will therefore see the benefits in years to come. Mrs. B believes that the key to Second Step’s success is that the school district has adopted it. Therefore, they are investing in training teachers for how to use the program. Due to this support, Mrs. B feels confident in the lessons she is delivering. This suggests that successful programs are ones that are supported by school districts and therefore administrators. Second, Mrs. B speaks highly of facilitators that create a space “where students feel as though they can talk openly” about how they engage with media. She references “cool” workshop leaders that are “checked in” and can create a space “…where sometimes they talk about subjects that are taboo but in a very open and respectful way.” Spaces with relatable and unthreatening facilitators can then create room for natural learning.

Lastly, Mrs. B believes that consistency is essential in determining the success of a program. A previous program implemented by the school counsellor allowed for students to come together each week allowing for relationships to be built between the students and the counsellor. As the program progressed, students were more willing to open up. Unfortunately, the program lacked long-term consistency and ended after two years. Mrs. B is regretful as she believed that “…it had potential to be a phenomenal program for the kids.”

Similarly, Espinoza, Penelo, & Raich (2013)found the benefits in using one-time targeted workshops in addition to media literacy programs. Specifically, researchers found that consistent programs worked to support the use of one-time targeted workshops. The study compared the impacts of a media literacy only program(ML)with a program that utilized both media literacy and a one-time targeted program (ML+ NUT). While both groups improved body satisfaction, the ML+ NUT group showed a higher increase. However, 7 months after the programs ended, body satisfaction decreased for both groups(Espinoza et al., 2013). Researchers note that these findings suggest the need for both consistent programs in mitigating body dissatisfaction, as well as the need for media literacy programs to be coupled with one-time targeted workshops(Espinoza et al., 2013).By including both targeted and consistent methods, this may give students the chance to process emotions, deconstruct how they feel, and provide opportunities to use critical thinking skills.

Conclusion:

Developing digital literacy is essential in providing young people with the tools to participate with social media platforms critically and responsibly. As participation in social spaces expands, now more than ever is the time to focus on developing these skills. If digital literacy programs are not implemented, children maybe unable to keep up with the dynamic social world and reject the pressures that come with it. Most worrisome is that mental health issues will continue to emerge with links to social media use. As a result, systemic changes are needed. First, teacher training programs should focus on including digital literacy knowledge so that educators are equipped to teach it to their students. Second, school districts must reimagine how to utilize all school personnel to teach digital literacy and include sufficient training for current educators. Finally, school districts must continue to adopt the use of outside programs to complement in-class objectives. What these findings reveal is that social media is forcing the development of an entirely new branch of learning. It requires trained professionals and consistent delivery to give young people the tools to participate in the social world.“ Digital media use is beyond watch out for the predator online, ”Mrs. B says.“ It’s now conversations about mental health, time management, about focus, about priorities, about making decisions that what will impact you in the future, about consent, and healthy relationships. It’s a lot.”

Works Cited

BC Government. (n.d.). Applied Design, Skills, and Technologies. Retrieved from https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/adst/7/core.

Bilodeau, H., Kehler, A., Minnema, N. (2021). Internet use and covid-19: How the pandemic increased the amount of time Canadians spend online. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2021001/article/00027-eng.htm.

Butler, A. (2020).Educating media literacy: The need for critical media literacy in teacher education. Leiden: Brill.

De Abreu, B. S.(2019).Teaching Media Literacy: Vol. Second edition. ALA Neal-Schuman.

Hawgood, A. (2022). What Is ‘Biogorexia’? A social media diet of perfect bodies is spurring some teenage boys to form muscle dysmorphia. New York Times. Retrieved from

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/05/style/teen-bodybuilding-bigorexia-tiktok.html.

Hjetland, GJ., Schønning, V., Aasan, BEV., Hella, RT.,& Skogen, JC. (2021). Pupils’ Use of Social Media and Its Relation to Mental Health from a School Personnel Perspective: A Preliminary Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18 (9163), 9163.

https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.3390/ijerph18179163.

Holland, G., & Tiggemann, M. (2016). A Systematic Review of the Impact of the Use of Social Networking Sites on Body Image and Disordered Eating Outcomes. Body Image,17, 100–110.

https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.008.

Mac, R., & Silvermann, C. (2021).Facebook is building an Instagram for kids under the age of 13. Buzzfeed News. Retrieved from https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/ryanmac/facebook-instagram-for-children-under-13.

Media Smarts A. (n.d.). Digital Literacy Fundamentals. Media Smarts. Retrieved from https://mediasmarts.ca/digital-media-literacy/general-information/digital-media-literacy-fundamentals/digital-literacy-fundamentals.

Media Smarts B. (n.d.). The Intersection of Digital and Media Literacy. Media Smarts. Retrieved from https://mediasmarts.ca/digital-media-literacy/general-information/digital-media-literacy-fundamentals/intersection-digital-media-literacy.

Merga, M. K. (2019). Librarians in schools as literacy educators: Advocates for reaching beyond the classroom. Palgrave Macmillan.

O’Reilly, M. (2020). Social Media and Adolescent Mental Health: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Journal of Mental Health, 29(2), 200–206. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1080/09638237.2020.1714007.

Posavac, H. D., Posavac, S. S., & Weigel, R. G. (2001). Reducing the Impact of Media Images on Women at Risk for Body Image Disturbance: Three targeted interventions. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 20(3), 324–340. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1521/jscp.20.3.324.22308.

Schimmele, C., Fonberg, J., Schellenberg, G. (2021). Canadians’ assessments of social media in their lives. Statistics Canada. https://doi.org/10.25318/36280001202100300004-eng.

Searing, L. (2021). One-third of children ages 7 to 9 use social media apps, Study Says. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/social-media-young-kids/2021/11/19/3130ce5a-488a-11ec-95dc-5f2a96e00fa3_story.html.

Smolak, L., & Levine, M. P. (2001). A Two-Year Follow-Up of a Primary Prevention Program for Negative Body Image and Unhealthy Weight Regulation. Eating Disorders, 9(4), 313–325.

Twigg, L., Duncan, C., & Weich, S. (2020). Is Social Media Use Associated With Children’s Well-being? Results from the UK household longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence,80, 73–83.

https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.02.002.

Vogel, E. A., Rose, J. P., Roberts, L. R., & Eckles, K. (2014). Social Comparison, Social Media, and Self-Esteem. Psychology of Popular Media Culture,3(4), 206–222.

https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1037/ppm0000047.

Vries, D. A., Peter, J., Graaf, H., & Nikken, P. (2016). Adolescents’ Social Network Site Use, Peer Appearance-Related Feedback, and Body Dissatisfaction: Testing a mediation model. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45 (1), 211. https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.1007/s10964-015-0266-4.

Wells, G., Horwitz, J., & Seetharaman, D. (2021). Facebook knows Instagram is toxic for teen girls, company documents show. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-knows-instagram-is-toxic-for-teen-girls-company-documents-show-11631620739.

Yamamiya, Y., Cash, T. F., Melnyk, S. E., Posavac, H. D., & Posavac, S. S. (2005). Women’s Exposure to Thin-and-Beautiful Media Images: Body image effects of media-ideal internalization and impact-reduction interventions. Body Image,2(1), 74–80.

Yang, H., Wang, J. J., Tng, G. Y. Q., & Yang, S. (2020). Effects of Social Media and Smartphone Use on Body Esteem in Female Adolescents: Testing a cognitive and affective model. Children, 7(9), 1.

https://doi-org.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/10.3390/children7090148.