Ian Lau

Ian Lau is a student in the Bachelor of Arts with a Major in Interdisciplinary Studies program at Capilano University. He has experience in various fields, and has offered his creativity in these areas of interest. He plans to explore his many interests further, and to work in a field where his creative ideas can be shared and realized.

A woman steps into the expansive store, filled with products of every kind. Her eyes passover the many items that cover the walls and sit on the shelves. Maybe she’s looking for a new winter coat, or a quick snack for later. Maybe she is searching for items that soften her blow against the environment. The ethically-sourced fabric catches her eye, as does the vegan, organic salad she plucks off the shelf. She happily purchases the items, satisfied with her eco-friendly contribution. Unfortunately, she had unknowingly bought into a phenomenon known as green washing. Greenwashing can be defined as, “The intersection of two firm behaviours: poor environmental performance and positive communication about environmental performance” (Delmas and Burbano 64-87). Poor environmental performance can be understood as a lack of meaningful action towards environmental change, such as pollution, and positive communication about environmental change can be defined as language that indicates that positive environmental change is being made. In its simplest form, we can understand greenwashing as instances of misleading messages that do not effectively reveal the potential negative impacts of whoever is sharing those messages. This is not an uncommon practice, as it has been found that“95% of products claiming to be green in Canada and the USA” have demonstrated greenwashing in their practices (de Freitas Netto et al.). Maybe the company behind the woman’s brand new, ethically-sourced coat has made vague claims to cover up their true environmental impacts. Maybe the vegan salad the woman happily purchased failed to address the massive amounts of energy used to produce the ingredients and the packaging. It is clear that she is a victim of greenwashing. With instances of greenwashing growing in prominence, it is important to resist these misleading messages in order to minimize unsustainable purchasing behaviour. Todo so, both consumers and companies must take responsibility for their actions that allow greenwashing to exist in the widespread form it takes.

I was only a child when I noticed myself gravitating towards environmentally-friendly ideas. The words reduce, reuse, and recycle were influential enough to me that I was happy to view the world through green lenses whenever these buzzwords littered the packaging. Was it the public education system that informed my opinion on the environmental impact of humans? Did these revelations shape my desire for sustainable practices in daily life? All I know is that I, and many others who have grown up in similar situations, care. We care about climate change and the future of our planet. When we see an item wrapped in green plastic, we believe in the power of our buying habits. I was about 12 years old when I excitedly picked up the green USB drive from the shelf, as I had been trained to seek out products just like it. I convinced my dad to pay extra for this item, over the countless other options that lined the wall. In my mind, this uniquely-coloured product that claimed to be eco-friendly was worth my purchase. Looking back now, I realize that I may have been misled. How could I be sure that those claims were true?Additionally, how many other times have I willingly purchased ‘green’ products without being aware of the unsustainable truth behind the product? Situations such as this made me realize how much research I must do about my purchases to truly be an environmentally-conscious consumer.

Today, as I enter the store as a consumer with the intention to purchase, I am more aware of greenwashing. I look at the products in front of me once again, but with a different perspective than the one I had when I looked at those USB drives many years ago. Standing in this corporation-owned space and staring at the deceptive marketing tactics scattered about, I can’t help but to compare this store to the businesses that have made meaningful efforts to adopt a sustainable outlook. FABCYCLE, a social enterprise that aims to provide a purpose for textile waste, is one of these businesses. According to Irina McKenzie, founder of FABCYCLE, the materials sold at the small business are “…all usable stuff that people or businesses don’t need anymore.” This is the antithesis of stores that do not prioritize the environmental impacts of their items. With this in mind, I can assess my trip to the store critically.

As mentioned previously, greenwashing can broadly be understood as a lack of accurate or sufficient communication regarding a company’s environmental messaging in combination with negative environmental performance. This can be applied to the bottled water that I had come across. Through specific use of language on the packaging, the water company promises natural and chemical-free spring water, bottled up carefully and with a lighter environmental footprint as a priority. These are the positive environmental claims that are in our interest today.In reality, this message does not address the steps taken to achieve sustainable goals, and does not tackle the major concerns regarding bottled water. To further illustrate this instance of greenwashing, we can look at FIJI Water’s website, where the company emphasizes that their bottles “…are made from high-grade PET (polyethylene terephthalate)” (Austyn Frostad), a supposedly recyclable, transformable, and more sustainable plastic. However, this plastic has been found to be insufficiently biodegradable to have any discernible positive environmental impact, while also failing to address the issue of water bottles often being discarded unsustainably (Hiraga et al.). This is a textbook example of greenwashing, and it is an instance that many of us can relate to through our own observations.

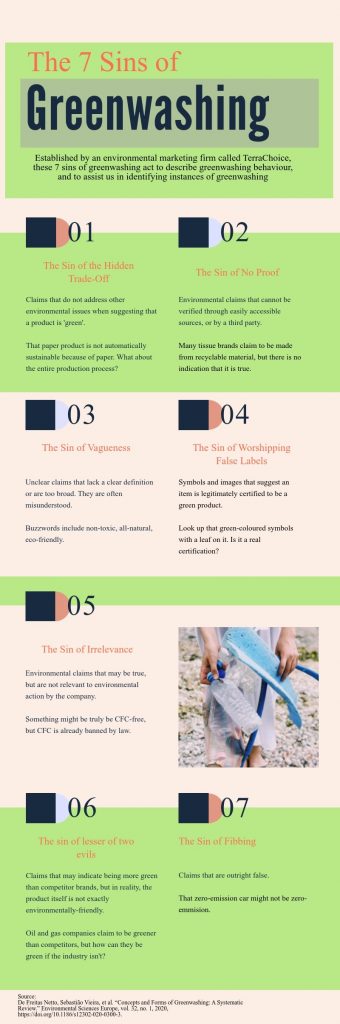

With this example of greenwashing in mind, we can dissect the concept into specific components of greenwashing, thus allowing us to understand the phenomenon better. De Freitas Netto et al. identify multiple forms and characteristics of greenwashing, with those being selective disclosure, decoupling, and corporate legitimacy theory. Selective disclosure can be defined as retaining negative information and disclosing positive information about a company’s environmental impact. In the case of bottled water, expressing the use of more eco-friendly plastic while avoiding a mention of the plastic pollution problem deeply rooted in the bottled water industry is a strong example. Decoupling refers to the acts of symbolic action to dissociate a company from negative environmental impact, often to satisfy “…stakeholder requirements in terms of sustainability but without any concrete action” (Siano et al. 27-37). This can be connected to the use of certain words or phrases on bottled water to elicit a positive opinion on a brand’s sustainability, such as vague promises of reduced carbon emissions. This all ties in with corporate legitimacy theory, which suggests that moral judgements, assumptions, and perceptions towards a product or corporation contribute to a standard of eco-friendliness that companies are encouraged to abide by. In other words, these bottled water companies continue to mislead consumers due to a shift in expectations and reactions from others. The corporations operate under the guise of entities that are committed towards environmental social values. In addition to these facets of greenwashing, a classification known as “the seven sins of greenwashing” have been cited in literature about the topic, giving us even more insight on the specifics of the practice (de Freitas Netto et al.). These various aspects of greenwashing shed light on the complexity and range of the phenomenon, and grant us a valuable understanding of the products that we consume.

I decide to quench my thirst at a later time, as I set the package of bottled water down and continue with my shopping.. I’m in the market for a set of wireless earbuds, so I head towards the electronics aisle for a suitable product for my needs. A specific earbuds box stands out. Not because it is pretty, or because it’s on sale, but because of the small label slapped on the bottom of the box. It is a tiny, green globe symbol that has the term “eco-friendly” written alongside it.This vague symbol of sustainability is a potential source of misleading green marketing, as it commits one of the aforementioned sins of greenwashing. My immediate reaction is surprise, as I personally do not associate the headphone industry with environmental efforts. This contrasts with bottled water, which many of us may be conditioned to associate with recycling, landfills, and pollution. The presence of such marketing tactics on so many different products reveal that greenwashing has become increasingly prominent, and will continue to do so.

To better understand why this influx of deceptive behaviour is happening, we have to understand that there is an increase in demand for green brands, as consumers are becoming more aware of global warming and other changes in the environment (Hameed et al.13113–13134). This encourages companies to implement environmentally conscious tactics into their messaging and practices, whether or not they actually make a meaningful effort to operate sustainably. A study has found that “66% of global consumers are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products” (de Frietas Netto et al.), indicating that a significant portion of consumers are potential targets of green marketing. This confirms to us that it would not be unusual for companies to shine a sustainable light on themselves in order to drive sales. This also explains why any type of product, such as the aforementioned earbuds, would be willing to engage with greenwashing behaviour. This shift towards environmentally friendly purchases has become so widespread that “Companies are adopting green marketing strategies to achieve a competitive advantage” (Hameed et al. 13113–13134), giving further confirmation that profits are what drive companies to give attention to what people are saying. As Irina McKenzie explains it, “If people demand something, businesses will listen”.

These companies from many different industries clearly take advantage of the tendency to gravitate towards sustainable items. They often incorporate these tactics as a way to sell their products, but is it possible for these companies to truly make an environmental effort? Without sufficient proof of significant action, it is not often the case. On the topic of specific industries, Irina McKenzie describes the operations within the textiles industry, saying that, “Like any other industry, most of the practices we have are not stemming from sustainability”. This puts into perspective what the majority of companies are truly enacting when making sustainability claims. These industries, whether it be textiles or electronics, are deeply rooted in unsustainable practices that companies cannot simplify with buzzwords and vague labels. For example, the earbuds industry has major environmental issues with questionable recyclability and land and water pollution (Dragan), which cannot possibly be addressed through common greenwashing marketing tactics. It is clear that greenwashing claims may not reflect on a company’s sustainable actions and values, but rather display a company’s relevant approach to selling a product. Because of this, it is important to understand that greenwashing is becoming more common in many different industries, and that green marketing mainly serves to increase profit rather than to fulfill any sort of sustainability goal.

Bingaman et al. that investigated the effectiveness of inoculation messages to combat greenwashing. By exposing the experimental group with an inoculation message that aims to inform about misleading marketing and sustainability, “participants in the inoculation condition were less likely to purchase” products that had expressed clear signs of greenwashing (Bingamanet al. 1-13). This indicates that awareness truly is important in the resistance against greenwashing, and suggests that we can spread that awareness as a way to assess this deception together. The study supports critically assessing these products, which aligns with Irina McKenzie’s thoughts on a consumer’s role in a society where greenwashing thrives. She asserts that we “Already have that critical thinking skill, but just apply it to anything that doesn’t feel right or doesn’t make sense. Go ask. Look for reviews. Ask your friends. Look it up, and really challenge the businesses. If they have a statement, ask publicly, or privately.”

As explained earlier, FABCYCLE is a business that aims to truly take sustainable initiatives in their practices. This includes spreading environmental awareness, which, as we have established, is also instrumental in making the right decisions in the face of greenwashing.Irina states that, “Awareness and education is a really important part of what [they] do”. There is a question, however, about how that awareness can be spread. How can we educate each other about products, the environment, and greenwashing? One of the main methods that FABCYCLE, other businesses, and other individuals use to inform and get informed is through social media.Through social media, we are all connected. We can throw our thoughts out into the open, and just as easily consume information that comes our way. Is there a method in which I can let the world know about the sustainable alternatives to wet wipes, and maybe to spread inoculation messages that work towards positive consumer behaviour? Of course. It is only a few keyboard taps away. For businesses, the online world is valuable in communicating whatever it is they desire to share on a scale that would otherwise be unachievable. For FABCYCLE, Irina mentions that “that’s why [they] try to do a lot more work on social media, because [they] can reach out to more people”. With sustainable business owners turning to social media to spread awareness to consumers, we know exactly where we can go to educate ourselves even further. These are just a few examples of effective strategies that can be employed to inform us and help us make better environmentally-conscious decisions.

Clearly, greenwashing exists. All those products that I have encountered are examples. At this point in my journey, I hope that it is also clear that greenwashing is bad. Of course, there is no way that downplaying or concealing unsustainable practices can be positive, but how negative can the act of greenwashing truly be? The answer may lie in the unassuming pair of socks that hang in front of me. The lime green piece of cardboard that wraps around the socks explains that they are made from bamboo. Upon closer inspection, the minimal packaging clarifies that the socks are actually made from a material known as rayon, derived from bamboo. If you have been following along, you can accurately expect to learn that rayon is absolutely not a sustainable fabric. Bamboo must go through a chemical process that has negative impacts on the environment in order to create rayon from it (Rocky and Thompson 1-9). Because of this, many fabrics are quick to label themselves as bamboo, when in reality, bamboo is only a barrier to attempt to cover up the environmentally-damaging practices hidden in plain sight. These socks may be devastating on their own, but they are only an introduction to the true menaces of greenwashing, known as the fashion and textiles industry.

In the fashion and textiles industry, greenwashing is notoriously rampant. From fast fashion, to vague reports, to the aforementioned deceptive material descriptions, this sector of production and consumption is teeming with misleading practices that seem to embed themselves into every single fibre and thread. In other words, greenwashing in the fashion industry is common to hide very unsustainable behaviour and causes consumers to contribute (Alexa et al.263-268). Additionally, “Greenwash undermines the whole cluster of green selling” (Hameed et al. 13113–13134), indicating that innocent brands and products are also hurt by the state of greenwashing. With how dominant brands such as H&M are when it comes to fashion, it is difficult for consumers to truly make green practices. The industry is built on unsustainable practices, and it drags consumers with them in the accountability of their actions. The largest companies, like H&M, engage in fast-fashion models, which make use of constant production of fashion items with short life cycles. This makes these clothing items prone to being thrown out often and polluting through landfills (Alexa et al. 263-268). With every purchase, consumers may unwillingly be practicing unsustainability by supporting these practices. To say that greenwashing is simply bad would be an understatement. When entire industries are built on this phenomenon, it paints a green picture that tells us that a change in our current, widespread ways of operating is necessary in order to achieve our sustainability goals.

In times like this, when the fashion industry continues to make little to no change to their damaging greenwashing behaviour, it is up to others to work towards meaningful change. We can see how certain companies and businesses make efforts to reshape and address the industry from within. FABCYCLE, being a social enterprise that works with textiles, is able to do what they can to help alleviate the environmental impact of the industry. To quote Irina, FABCYCLE is“Not here to sell fabric”, but rather “To move usable resources”, showing us that a business does not have to confine themselves to the questionable environmental standards of the industry.Businesses can aim to inform, such as through social media, and make sustainable change, rather than greenwash for profit. When it comes to FABCYCLE, “In the big scope of things, [they’re]very, very small”. They are only able to make meaningful change to a certain extent, due to the sheer size of an industry as big as textiles, but they are a prime example of what can be done in their position to fight against a notoriously greenwashed industry.

I begrudgingly toss a few pairs of decent socks into my basket, knowing that, at this time, there may not be a perfect solution to such an endemic environmental issue in the industry. Despite my hesitation, I am still satisfied with my ability to dodge some of the most apparent instances of greenwashing. I realize that I am responsible for making these informed decisions, as are the companies for continuing to prioritize profits over all else. Is it possible that I, an individual consumer, holds as much significance in the presence of greenwashing as the people behind the corporations that utilize the tactics themselves? When reflecting on this, it is important to recognize that these corporations, the ones that present to us their products, consist of individuals as well. Irina states that these businesses are “Not a big corporation that’s disconnected from the people [they] serve”. With this in mind, we can understand how those who are behind greenwashing can, in fact, reshape the greenwashing landscape from within. Irina also mentions that “You have to be responsible for yourself”. If that is the case, both consumers and corporations hold this responsibility in diminishing the existence of greenwashing.

I pay for my items and I leave. With one foot out the door, I think about what I can do now. What can I do to continue to fight against misleading green marketing? If the ones buying the products are not enough to shift the world of marketing away from greenwashing, the ones behind how our society operates may be the ones we must see action from. “It is really important that individuals are demanding more transparency and more comfortability,” explains Irina.“However, it is on the policymakers to make the changes to ensure that they’re implemented on a larger scale”. As established previously, these policymakers are individuals just like you and me, meaning they also hold a responsibility in the state of greenwashing.

If there is anything positive about greenwashing, it would be related to how it represents the consumers that make up our society. It sheds light onto the changing mindset of people as a whole. The fact that “…consumers stop buying [greenwashed] products, which they feel are harmful to the environment” (Hameed et al. 13113–13134) tells us that people truly care about making sustainable decisions with our wallets. Additionally, “Accusations of greenwashing, along with consumer awareness, can harm a brand by significantly and negatively affecting consumer’s purchase intentions” (Bingaman et al. 1-13), which suggests that we may be making progress in the resistance against this deception. Greenwashing reveals to us that people are caring about the environment enough that we are willing to make personal changes to sustain our planet. As Irina puts it, “The fact that companies are even using that method, greenwashing, using sustainability as a marketing feature, it just signals that there’s awareness by consumers that this is an important thing to say”.

Greenwashing is everywhere. Through my trip to the store, I was able to identify the existence of the phenomenon as it crept up on the shelves over and over again. There is much to understand about the subject, but I am satisfied that I have the tools at my disposal to reflect on my purchases. As I step out of the corporate enterprise that will surely appreciate my monetary offerings, I feel accomplished. The bags I carry contain a look into my decisions as a consumer. The sustainable products that I have carefully chosen to take home today are symbolic of my self-imposed responsibility as an environmentally-conscious individual. I am happy to be aware of greenwashing and understand why I must be wary of it, and happy to be able to navigate past many products guilty of said practice. I can be angry at the devastating actions of the industries that abuse greenwashing for profits, thus impacting everyone and everything involved in their operations. I can also be optimistic as I reflect on the rising prominence of eco-friendly behaviour and mindsets among my fellow consumers. Through this short, typical voyage to the store, I realize that the path ahead is not the short walk from the store to my home, but a lifelong journey. I look at the single-use straws I willingly added to my inventory, and realize that the road to sustainability will require major changes in practices, policies, and mindset, starting with the individual I know best.

Works Cited

Alexa, Lidia, et al. “Fast Fashion – an Industry at the Intersection of Green Marketing with Greenwashing.” International Symposium “Technical Textiles – Present and Future”, 2022, pp. 263–268., https://doi.org/10.2478/9788366675735-042.

Bingaman, James, et al. “Inoculation & Greenwashing: Defending against Misleading Sustainability Messaging.”Communication Reports, 2022, pp. 1–13., https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2022.2048877.

De Freitas Netto, Sebastião Vieira, et al. “Concepts and Forms of Greenwashing: A SystematicReview.” Environmental Sciences Europe, vol. 32, no.1, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-0300-3.

Delmas, Magali A., and Vanessa Cuerel Burbano. “The Drivers of Greenwashing.” California Management Review, vol. 54, no. 1, 1 Oct. 2011, pp.64–87., https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2011.54.1.64.

Dragan, Lauren. “Your Wireless Earbuds Are Trash (Eventually).” The New York Times, The New York Times, 26 Feb. 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/wirecutter/blog/your-wireless-earbuds-are-trash-eventually/.

Frostad, Austyn. “What Kind of Plastic Does Fiji Water Use to Make Their Bottles?” FIJI Water, https://www.fijiwater.com/blogs/faqs/what-kind-of-plastic-does-fiji-water-use-to-make-their-bottles.

Hameed, Irfan, et al. “Greenwash and Green Purchase Behavior: An Environmentally Sustainable Perspective.” Environment, Development and Sustainability, vol. 23, no. 9,2021, pp. 13113–13134., https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-01202-1.

Hiraga, Kazumi, et al. “Biodegradation of Waste PET.”EMBO Reports, vol. 21, no. 2, 2020, https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201949826.

Rocky, Bahrum Prang, and Amanda J. Thompson. “Production of Natural Bamboo Fiber—2: Assessment and Comparison of Antibacterial Activity.” AATCC Journal of Research, vol.6, no. 5, 2019, pp. 1–9., https://doi.org/10.14504/ajr.6.5.1.

Siano, Alfonso, et al. “‘More than Words’: Expanding the Taxonomy of Greenwashing after the Volkswagen Scandal.” Journal of Business Research, vol. 71, 2017, pp. 27–37., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.11.002.

Hello Ian!

I must say, this article you wrote really made me more aware of the products that I’m buying. Not only was it informative, but after reading it, I was more conscious about the products that I was buying. I used to like this snack and the packaging said it was eco-friendly, but after closer examination I realized how much plastic and containers it had and thought to myself: there’s no way this is in any way eco-friendly. It’s safe to say I won’t be buying that snack anymore. We must do whatever we can to help our planet. I wish you the best of luck in your future endeavors!

I agree!