Edmund Strachan

Edmund Strachan currently holds two associate degrees, one in Social Service Work and another in ecological restoration and is about to graduate with a B.A in Interdisciplinary studies. He has a publication within UVIC’s ECO restoration Journal and holds two professional certifications in Environmental Protection and Sediment and Erosion Control Specialists with the province of British Columbia. He has worked as a Social Worker within the city of Toronto for over 10 years. Edmund is looking towards a master’s program at UBC or SFU to further investigate the relationships around community and nature.

Dedications/Acknowledgements

I would first like to acknowledge that the research for this paper was conducted on the traditional unceded territories of the Squamish, Tsleil-Waututh, and Musqueam First Nations. Special thank you to Professor Leah Bailey and Cassidy Picken for providing guidance and inspiration in writing this project. Thank you, Claire McGillivray, of the Edible Garden Project, for providing your expertise during the interview process. Thank you, Jo Fitzgibbons, for providing your expertise and valuable advice. Thank you to the environmental technicians who assisted me with my research and provided their expertise. Lastly, thank you to Capilano University for allowing me to share my research with the community.

Personal Narrative

As a Black man living in the Lower Mainland region, people have often perceived me as a threat. However, sharing food and creating community have enabled me to break down some of those barriers and increase community cohesion across racial and cultural boundaries.Gardening activities have fostered ecological resilience within my community by providing habitat and food for local fauna while promoting strong networks in which community members bonded and trade healthy foods with one another. When I reflect on my experiences working as a social worker within urbanized Toronto, I can see the mental health benefits of having access to civic ecological activities such as gardening and how environmental stewardship programming could empower vulnerable communities. Civic ecological initiatives provide a safe place for public engagement while providing individuals with an opportunity to disengage with current life issues, reflect and reconnect with nature in a non-threatening environment.

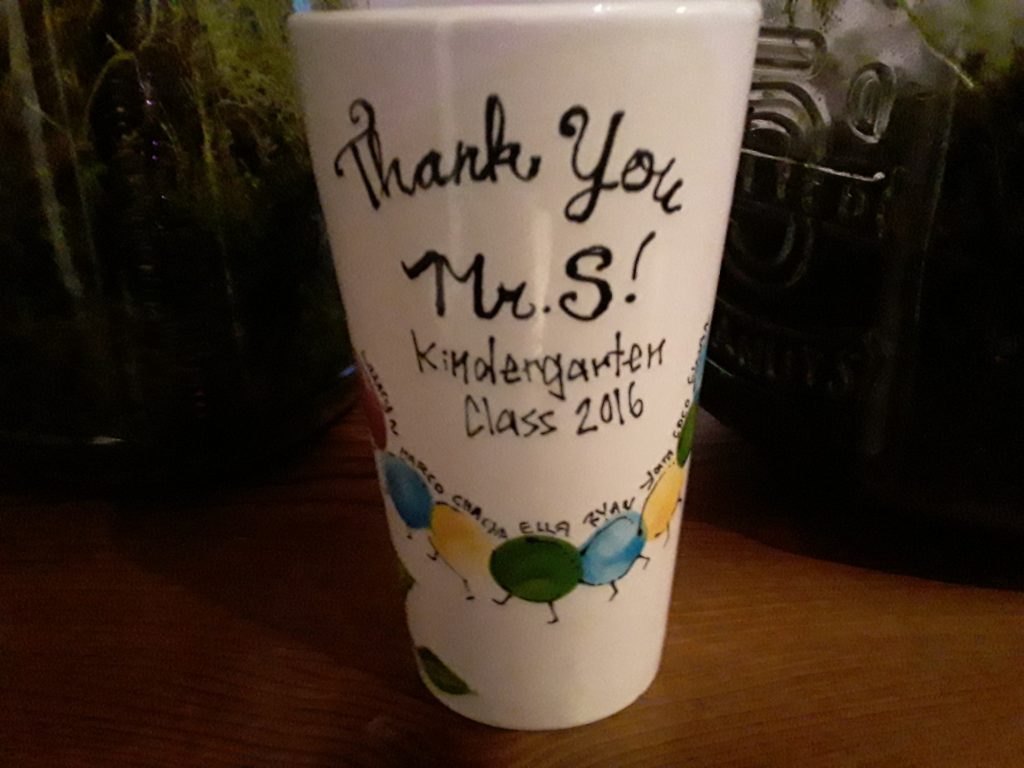

In 2016, I worked as an educational assistant at a Lower Mainland elementary school in a region that is surrounded by nature and rooted in privilege. This was a stark contrast when compared to my previous work in disadvantaged regions around Toronto with limited access to nature. Upon reflection, a particular case struck me, as I was assigned to a student in the lower grades whose anxiety was so overwhelming that situations often turned physical. Assigned tasks during lessons would often result in a loss of motor control functions, which led to the student punching, kicking, and biting faculty members who were attempting to gain control of the outbursts. These instances of anxiety and physical altercations resulted in the student being designated to half days at school. The removal of the student from class had major ramifications on their educational goals and social development and left them in a state of constant guilt. By implementing civic ecological practices such as nature walks and gardening, I was able to stabilize the student’s behaviour, which allowed a full return to school. My recommendations to establish a garden program created a safe environment, which encouraged positive social interactions between other students and faculty.

After a productive day within the classroom, on a sunny afternoon at the elementary school, the student and I went to attend the garden as per our newly established routine. As we approached the garden, I heard the student ask me,“Mr. S! Does nature make you happy?” I replied,“Yes! Does it make you happy as well?” The students’ reply was surprising yet simple. They said, “Yes, especially when I feel down, I can come out here and focus on something other than how I feel.” Upon reflection, this experience was a turning point that drew me to the natural world and environmental sciences. I began growing my food and eating it, which filled me with a sense of accomplishment. More importantly, sharing the food I grow creates opportunities for me to interact with community members who would normally not interact with me. In theLower Mainland, and especially on the North Shore where I live, the demographic is predominately white (StatsCan, 2016).The act of sharing food is a non-threatening gesture that often generates conversations and builds trust, overcoming pre-conceived judgments on my appearance.This fact became apparent as many students attending the school would often approach me wanting to engage in conversation and be involved in the gardening activity.

Introduction

Globally, issues of food insecurity, biodiversity loss, climate change, and a growing disconnect with our natural environments are increasing (Whittman et al., 2017). A surprising statistic revealed that “1 in 9 households within British Columbia”could be considered food insecure, and 1 in6 children are experiencing some level of food insecurity (Vancouver Coastal Health, 2020).Furthermore, the Covid -19 pandemic is currently having a significant impact on our communities’ mental and physical health. This year, 23% of young adults aged 25-44 have screened positive for depressive and anxiety disorders, an increase of 4% from last year (Stats Canada, 2021). Programs within civic ecology address issues of mental health and food insecurity by promoting strong community relationships and empowering members to grow their food.Civic ecological practices have been utilized in the state of California within therapeutic applications at various women’s shelters, prisons, and hospitals around the state, that had participants growing food for their communities as a form of self-healing and mental health maintenance (DelSesto et al., 2015). Additionally, this field of study employs environmental conservation and gardening techniques, to provide environmental education on habitat protection and build social-ecological resilience in response to climate change (Maharrammli et al., 2021; Kransy, 2018).

Civic ecology is an interdisciplinary field of study that addresses a fundamental misconception that humans are separate from nature by encouraging community and environmental initiatives while empowering individuals who participate (Kransy, 2018).This article seeks to understand current civic ecological programs within the Lower Mainland region and highlight their benefits, such as building social-ecological resilience, providing food security, and incorporating local knowledge in climate change adaptation planning. In addition, challenges for these programs are discussed, which include accessibility for vulnerable and BIPOC community members, lack of government funding, and green gentrification of disadvantaged communities.Potential solutions are proposed, which included anti-displacement policies on housing, development of recurring provincial grants, modification of publicly owned spaces, and investment into equity-seeking grassroots movements. Additionally, increased communication and collaboration amongst policymakers, developers, organizations, and communities on social-ecological initiatives are vital for generating diverse viewpoints within the discourse.

Methodology

Aldo Leopold, an American author, philosopher, ecologist, and conservationist, is credited for his “land ethic” theory as the basis for civic ecology (Kransy, 2018). The land ethic theory is described as viewing a community as more than just a region with people in it (Kransy, 2018). Rather, it includes all life forms such as the soil, water, insects, wildlife, vegetation, humans, and the atmosphere (Kransy, 2018). This paper employs primary research, using informal interviewing techniques with industry professionals in various fields of civic ecology.The land ethic theory is present within the practices of the various interviewed professionals as they seek to address issues of climate change and food insecurity while incorporating all aspects of a region within planning strategies. The interviewed industry professionals include environmental technicians, a community planner, and a food system manager. Secondary research is employed using several scholarly databases and non-governmental websites on the topic of civic ecological practices in North America and their impact on mitigating climate change effects, green gentrification, addressing food insecurity, and creating ecologically resilient communities.

Building Social-Ecological Resilience

Social-ecological resilience is the ability of a community and the environment to endure negative impacts and changes (Maharrammli et al., 2021). Civic ecology utilizes a systems perspective, in which people and nature are linked and influence one another (Maharrammli et al., 2021). As global concerns increase due to the growing climate crisis and the reduction of green spaces, a system lacking resilience and adaptive capabilities could have negative social and environmental impacts (Maharrammli et al., 2021). The communities that are most affected by this negative impact are vulnerable and BIPOC communities due to limited green spaces, unaffordable housing, and food deserts within communities.

When discussing social-ecological resilience strategies with an environmental technician in the Lower Mainland region, they stated, “We do have a lot of educational programs such as the park stewardship program that encompasses the human aspect within eco-resilience strategies, which can increase engagement of communities within their natural environment.These programs help create awareness of the negative impact humans can have on their environment.” Additionally,“Educational programs ensure that participants are equipped with the knowledge to support, enhance, and protect natural ecosystems and create eco-resilience within their communities”(personal interview, 2022).Outdoor education such as park stewardship supports a fundamental understanding of ecological knowledge while encouraging participants to interact with their natural environment. Participation in these programs increases community awareness of climate change issues within the region. Access to environmental education for communities is key to fostering social-ecological resilience (Maharrammli et al.,2021).

Food Security For Vulnerable Communities

One of the many challenges facing vulnerable and BIPOC communities within the Lower Mainland is food insecurity (Whittman et al., 2017).Food insecurity refers to people who lack sufficient access to nutritional food to meet their dietary needs, which is essential for an active and healthy lifestyle (Whittman et al., 2017).Civic ecological programs such as community gardens and local farms provide an exceptional opportunity to tackle this issue. Claire McGillivray, the program manager at the Edible Garden Project, said that “Our program provides individuals with an opportunity to connect with their food systems and gain knowledge of where their food comes from.” Furthermore, “It is a place where people can learn farming and gardening techniques and food growing techniques, which is important for urban neighbourhoods where a nature disconnect exits”(personal interview, 2022). The Edible Garden Project has been successful in the modification of public spaces, which provided access to green spaces for communities around the Lower Mainland. Vulnerable and BIPOC individuals can use the green spaces provided by the program for growing nutritional foods to meet their dietary needs. Furthermore, vulnerable and BIPOC individuals that do have access to green space but lack horticultural knowledge, can attend these programs, and develop the skills to grow their food within their local.

Financial constraints and lack of access to healthy foods are one of the primary barriers to food security within the developed world (Whittman et al., 2017).McGillivray and the Edible Garden Project actively address this barrier in the Lower Mainland region by,“Donating 100% of the produce grown within the shared garden sites to food banks ran by the North Shore Neighbourhood House, our parent organization.”In addition, “We have a provincially funded program that distributes 50 coupons per week to persons and families in need that can be traded at any farmers’ markets in British Columbia to purchase any unprocessed fresh foods, which includes meats, vegetables, cheese, and more.” McGillivray went on to say, “We are so much more than just a production farm! Our farms are about building community resilience and providing access to the most vulnerable of communities who would normally have limited access to these goods”(personal interview, 2022).Food banks within the Lower Mainland rely heavily upon community donations and play a critical role in addressing food insecurity issues within vulnerable and BIPOC communities. Shared green spaces managed by the Edible Garden Project and similar organizations ensure food banks are continuously stocked with healthy foods for the communities they support. Provincially funded programs like the coupon program offer vulnerable individuals a variety of opportunities to purchase foods that meet their dietary and cultural needs.These programs remove the stigma placed on vulnerable and BIPOC individuals, by providing them with equal opportunities to purchase fresh foods from markets that would normally be unattainable.

Honoring First Nations Food Sovereignty

Food security and sovereignty are issues presently impacting Indigenous communities within the Lower Mainland. A societal shift in perspective is required to accurately capture the distinct food systems used by Indigenous communities, which honors and respects their world views (Batal et al., 2021). Food sovereignty emphasizes Indigenous people’s close connection with their natural environment (Batal et al., 2021). It encompasses the efforts put into revitalizing Indigenous food systems, transferring cultural knowledge about their land, and harvesting traditional foods (Batal et al., 2021). Colonial policies such as residential schools, land privatization, government oversight, and overexploitation of resources have had a major impact on food sovereignty within Indigenous communities in the Lower Mainland region (Batal et al., 2021).

Although there is a long journey ahead to address these issues, some civic ecological partnerships have been established to tackle the problem of food sovereignty for Indigenous communities in the Lower Mainland. Jo Fitzgibbons, a planner with the Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation, comments, “We do have a couple of Indigenous-led projects such as Wild Salmon Caravan, which is focused on culturally important foods.” Furthermore, “We are actively trying to put equity-seeking in Indigenous opportunities first within our partnerships”(personal interview, 2022).In addition to the Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation, the Vancouver Foundation is an organization that supports equity and justice by investing $2 million into BIPOC communities (Vancouver Foundation, 2021). Some of the grassroots organizations it has invested in include the Northwest Indigenous Salmon Alliance, Indigenous Women Outdoor Society, and the Dasiqox Tribal Park Initiative (Vancouver Foundation, 2021). Like the Wild Salmon Caravan, the goal of these projects is to build coalitions that link Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to conserve, protect and restore wild salmon habitat along the Fraser River (Wild Salmon Caravan, 2022).By prioritizing equity partnerships within civic ecological strategies, we can address the food sovereignty needs of Indigenous communities in a way that respects and honours their cultural identity.

Incorporating Local Knowledge

One of the main distinctions within the practice of civic ecology includes people acting as stewards of their environment and community through the practice of gardening, tree planting, and watershed restoration (DelSesto et al., 2015). An environmental technician within the Lower Mainland stated,“When it comes to ecological restoration projects in the Lower Mainland region, positive relationships with park stewardship groups increase its success.” Additionally, “They are an important part of the monitoring and maintenance regime after the project’s completion”(personal interview, 2022).Park stewardship groups are critical for successful outcomes in restoration initiatives. The Lower Mainland region is a sizable zone that is difficult to maintain and monitor due to limited municipal personnel. Park stewards are often accustomed to their region and are aware of the challenges and goals outlined in environmental planning, which places them in the ideal position to ensure successful environmental outcomes.

Presently, several programs within the Lower Mainland region are encouraging more community-based science and making it easier to incorporate local knowledge in planning strategies. An environmental technician with the Lower Mainland region noted, “We have partnered with the public library to run an application called I Naturalist, which encourages community members to make observations and assist with species identification” (personal interview, 2022). Partnerships formed with local organizations such as stream keepers are provided with the necessary tools to collect data on their local environments. Once the data is collected that information is shared amongst partners.By encouraging community members to collect data on natural environments within their local, city planners can incorporate that information into their environmental planning strategies. The usage of applications provides easy access to educational opportunities for community participants and increases community engagement with their environment.

Even though stewardship programs provide valuable information for ecological management strategies, Fitzgibbons has noted,“Complications can arise as different groups utilize different methods of collecting data, which can become complex when trying to make an accurate analysis of the ecosystem within the region”(personal interview, 2022). A potential solution for this barrier is to have a uniform structure for how data is collected for different ecosystems within the Lower Mainland region. With limited human resources to maintain natural areas around the Lower Mainland region, community involvement in restoration activities has become more critical than ever. Community involvement ensures communities and natural areas are resilient to the impacts of climate change.

Barriers and Recommendations

Current programs offered within the Lower Mainland region are currently functioning to nurture social-ecological resilience within communities. However, Fitzgibbons has noted that the primary participants in stewardship programs are privileged people from a higher socioeconomic status with abundant recreational time.Furthermore,“a broader systemic issue prevents access for vulnerable communities, especially when affordability within the region is very low and families are struggling to support themselves”(personal interview, 2022). Government and non-governmental organizations(NGOs)need to provide more equitable opportunities for diverse demographics. Fitzgibbons mentions the Still Moon Art Society is one of several NGOs currently working to be proactive in addressing the lack of diversity within stewardship participation.StillMoon Art Society provides a plethora of programs in which individuals can engage at convenient times. This flexibility ensures everyone has an equal opportunity to be involved in community activities that promote human connection to the environment using art as a medium. Organizations like Still Moon Art Society and other grassroots movements are important for efforts to improve community cohesion and ensure equal opportunities are available, regardless of race, gender, or culture.

According to McGillivray, “One of the largest barriers facing non-profit organizations is the lack of consistent funding to support civic-ecological initiatives.”With so many different organizations competing for similar governmental grants, acquiring funding is a very time-consuming task. Moving forward, this barrier could be addressed through the development of recurring provincial grants which are primarily focused on supporting civic-ecological initiatives such as food production and restoration. Moreover, increased communication and collaboration amongst policymakers, developers, organizations, and communities on social-ecological initiatives and connecting resources are recommended (DelSesto et al., 2015). Such recommendations have the potential to increase the programming available for all citizens within the Lower Mainland region and increase the operational capacity for existing programs.

When enhancing and restoring natural areas around the Lower Mainland region, we run the risk of green gentrification. Sarah Dooling (2009), who coined the term, describes it as the implementation of environmental strategies in green spaces that lead to the exclusion of the most economically vulnerable communities (Dooling, 2009).This issue has arisen in regions around the Lower Mainland where developer sand planners intend to invest in improving areas that are dilapidated, resulting in the displacement of vulnerable individuals who lack the means to live in these enhanced regions. Fitzgibbons has commented on this issue, saying, “I think many regions struggle with this issue. However, there is research and organizations currently working on tackling this problem.Anon-governmental organization known as Greening in Place, located in the state of California, proposes potential solutions for green gentrification within developmental projects”(personal interview, 2022). Presently, there are limited protections in place for vulnerable and BIPOC communities within the Lower Mainland region.

One of the solutions proposed inGreening in Place is equitable green development (Gibbons et al., 2020). The proposed solution prioritizes investment and engagement for low-income communities to mitigate the impacts of ecological enhancements in dilapidated regions (Gibbons et al., 2020). Furthermore, these investments must be paired with policies that provide ample opportunity for disadvantaged communities and prevent displacement (Gibbons et al., 2020). One of the anti-displacement policies highlighted within the strategy includes tenant protections, which can mitigate the effects of green gentrification in regions and provide renter households with the stability they need to remain within communities (Gibbons et al., 2020).This policy will ensure planners and developers can effectively enhance regions while ensuring housing prices within vulnerable communities remain unchanged (Gibbons et al., 2020). Such policies would be beneficial for vulnerable and BIPOC communities within the Lower Mainland region as we struggle with housing affordability.

Moving forward, more governmental support for grassroots projects and civic ecological programs that encourage equitable opportunities for diverse demographics is needed. Governmental support in the form of increased funding, communication, and collaborative partnerships is valuable for empowering communities. The involvement of different ethnic groups within civic-ecological programs is important for developing eco-resilience, addressing food insecurity, removing appearance-based stigmas, and creating a sense of place and belonging within communities across the Lower Mainland.As stated within the land ethic theory, our communities are more than just the people who reside within them, and it is all our responsibility tore-establish our connection to nature to address the challenges of climate change.

Conclusion

Civic ecology is a unique practice that provides a multi-faceted solution for current societal issues such as climate change, food insecurity, and mental health. Programs in civic ecology have shown to provide an exceptional opportunity for communities to be involved in citizen science, environmental stewardship, and food systems. Participation in these programs can provide individuals with transferrable skills that have the potential to lead to employment opportunities and positive health outcomes. According to an environmental technician for the lower mainland region, “Participation within these programs has been proven to be beneficial to have on a resume when applying for positions within the environmental sector”(personal interview, 2022). Furthermore, McGillivray has noted, “A lot of people who have participated within their program have gone to work for other farms, started their farms, or have utilized the skills they acquired within their gardening projects”(personal interview, 2022).Such opportunities have the potential to increase social capital and community cohesion while improving the quality of life for all citizens within the Lower Mainland region. Further research by governmental organizations and academics into policy creation that promotes green spaces and modification of publicly unused spaces would prove beneficial for vulnerable and BIPOC communities.

Going forward, we must acknowledge the challenges people of colour face when having limited access to these programs. Major systemic changes within governmental policies are needed to provide fair opportunities for all citizens within the region. As a person of colour who has utilized these programs to breakdown barriers within my community and change public perceptions, I believe these programs are a necessary tool in tackling issues such as mental health, addressing racism, and food insecurity.

Works Cited

Batal, M., Chan, H., Fediuk, K., Ing, A., Berti, P., Mercille, G., Sadik, T., & Down, L. (2021). First Nations households living on-reserve experience food insecurity: Prevalence and predictors among ninety-two First Nations communities across Canada. Special Issue on First Nations Food, Nutrition, and Environment Study: Mixed Research. Retrieved March 12, 2022, from https://eds-b-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.bellevue.edu/Eds/Pdfviewer/Pdfviewer?Vid=16

DelSesto, M., Tidball, K., & Kransy, M. (2015). Civic Ecology: Adaptation and Transformation from the Ground Up. ebscohost.com. Retrieved 2022, from https://eds.p.ebscohost.com/eds/detail/detail?vid=16&sid=f1c0b2e7-fc60-4aa6-b1c5-04b941ecbfd1%40redis&bdata=JkF1dGhUeXBlPWlwLHVpZCZzaXRlPWVkcy1saXZlJnNjb3BlPXNpdGU%3d#AN=943463&db=nlebk

Dooling, S. (2009, October 6). Ecological gentrification: A Research Agenda Exploring Justice in the City. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. Retrieved March 12, 2022, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00860.x

Environmental Technician. (2022, February 11). Personal interview.

Environmental Technician. (2022, February 12). Personal interview.

Fitzgibbons, J.(2022, February 23). Personal interview.

Gibbons, A., Liu, H., Malik, F., O’Grady, M., Palacio, E., Perron, M., Trinh, S., & Trinidad, M.(2020). Greening in place. Greening in Place. Retrieved February 26, 2022, from https://www.greeninginplace.com/

Indigenous Food SystemsNetwork.(2022). Who we are and what do we do? Retrieved April 5, 2022, from https://www.indigenousfoodsystems.org/about

Kransy, M. E. (2018). Grassroots to Global: Broader Impacts of Civic Ecology. Google Books. Retrieved February 23, 2022, from https://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=aIJZDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=Grassroots%2Bto%2BGlobal%3A%2BBroader%2BImpacts%2Bof%2BCivic%2BEcology&ots=FFWW6HiNax&sig=gfm6uhGqofj0o3I2K_ezDyGedbs&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Grassroots%20to%20Global%3A%20Broader%20Impacts%20of%20Civic%20Ecology&f=false

Maharrammli, B., Bredow, V., & Goodwin, L. (2021). Using Civic Ecology Education to foster social-ecological resilience: A case study from Southern California. Taylor & Francis. Retrieved February 23, 2022, from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00958964.2021.1999886

McGillivray, C. (2022, February 14). Personal interview.

Statistics Canada. (2021). Census profile, 2016 census North Vancouver, District Municipality [Census Subdivision], British Columbia and Quebec [province]. Census Profile, 2016 Census -North Vancouver, District municipality [Census subdivision], British Columbia and Quebec [Province]. Retrieved March 12, 2022, from https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CSD&Code1=5915046&Geo2=PR&Code2=24&SearchText=Low&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=Visible+minority&TABID=1&type=0

Stats Canada. (2021). Survey on Covid-19 and Mental Health, February to May 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2022, fromhttps://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210927/dq210927a-eng.htm

Wild Salmon Caravan. (2022). A Celebration of the Spirit of Wild Salmon. Retrieved April 5, 2022, from https://wildsalmoncaravan.com/volunteers/

Wittman, H., Chappell, M.J., Abson, D., Kerr, R., Blesh, J., Hanspach, J., Perfecto, I., Fischer, J. (2016). A social-ecological perspective on harmonizing food security and biodiversity conservation. Regional Environmental Change.Retrieved March 12, 2022, fromhttps://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10113-016-1045-9

Vancouver Coastal Health. (2020). Food Insecurity in British Columbia (2020). Retrieved March 23, 2022, fromhttp://www.vch.ca/about-us/news/food-insecurity-in-british-columbia

Vancouver Foundation. (2021). 42-BIPOC led organizations were awarded funding to support their work on racial justice. Retrieved April 4, 2022, from https://www.vancouverfoundation.ca/whats-new/42-bipoc-led-organizations-awarded-funding-support-their-work-racial-justice