Dev Beniwal

Dev Beniwal is a Summer 2022 graduate from Capilano University’s Interdisciplinary Studies Program. He is a multilingual knowledge mobilizer and public communicator consistently capturing the issues at the intersections of Public Policy Research, International Relations, Social Justice, Technology, and Media. Inspiring him to go for his Masters in Law Enforcement Studies at Justice Institute of British Columbia.

Occupational gender segregation is currently a significant component determining gender inequality in the workplace. The pattern in which men and women work in distinct professions is occupational gender segregation. Various factors such as culture, discrimination, and individual qualifications reinforce occupational gender segregation and affect individuals’ workplace experiences (Cohen 890). Western labor markets have always segregated men and women, problems scholars have focused on since the 1960s. Although some studies suggest that the overall segregation has been decreasing gradually over the last several decades, which is a continued trend that began in the 1960s, others have reported prevalent occupational gender segregation, especially in Canada. I have lived in Canada and witnessed gender segregation; there is an evident difference in career paths men and women take and interests from an early age to higher education. Through an interview, a personal narrative, and scholarly research, this paper asserts that occupational gender segregation is prevalent in the workplace in Canada. It is further exacerbated by a gender pay gap and affects occupational status and opportunities for professional growth for women. Furthermore, women from minority communities face more inequalities based on their gender, race, and even immigration status. System-based solutions that create awareness of unconscious biases and the gender pay gap can help in reducing occupational gender segregation.

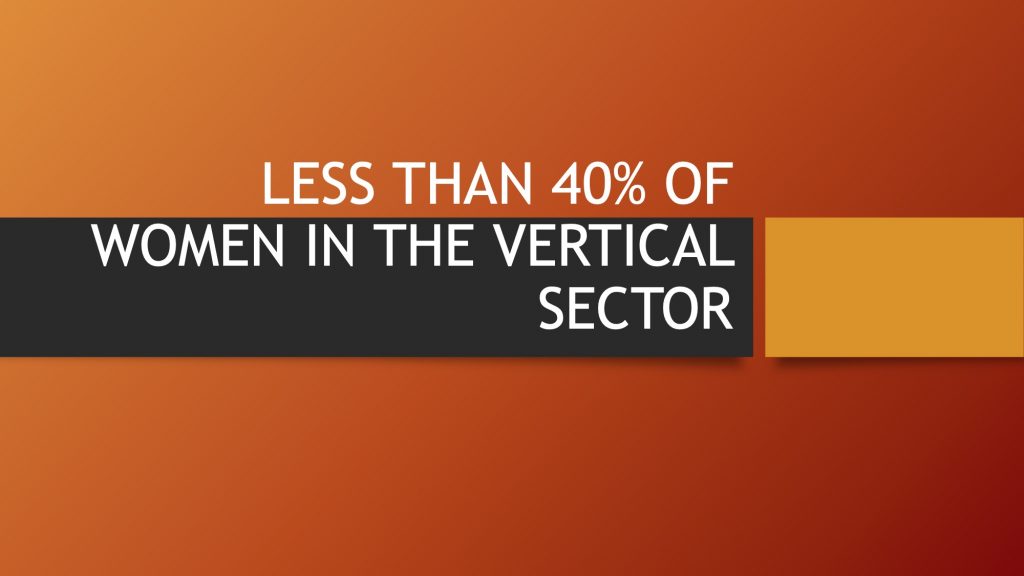

There are two types of occupational gender segregation, both of which are prevalent in the Canadian job market (Fortin 3). Horizontal segregation refers to occupational segregation between positions with the exact educational requirements but in separate areas of study (Fortin 3). Horizontal segregation is frequently connected with beliefs about gender roles, making it more prevalent. The foundations of horizontal gender segregation in professions have been thoroughly discussed, with many points of view expressed through sociology and psychology—gender stereotypes, for instance, and their consequences for academic and professional choices. Vertical segregation is defined as occupational segregation across different educational levels, expertise, and competencies (Fortin 3).

While occupational gender segregation occurs due to a complex interaction of personal and situational factors, it does not persist indefinitely but changes with time. Women’s labor-market outcomes in Canada have improved significantly over the last decade (Cortés and Pan 32). Closing the pay inequality has long been a focus of government leaders at all levels. Women are represented in different professions and levels within organizations, improving their labor force participation and thus closing the wage gap. Despite these improvements, there have long been concerns that the concentration of women in specific professions and within all occupations in specific activities has restricted their labor market outcomes.

The interview raised pertinent issues in occupational gender segregation. These issues prevent women from pursuing professional growth, aggravating occupational gender segregation. The interviewee is an advocate for gender equality. Among the essential issues from the interview is a significant gender disparity regarding women’s income and professional growth opportunities in the workplace. More importantly, the gender equality advocate notes that microaggressions are experienced by around 60% of women in the workplace in Canada. Microaggressions explain their exclusion, unconscious bias, and racism or ethnicity. A microaggression can appear in various indirect ways and is found all over the workplace. It might take the form of comments that are seen as bigoted, racist, hateful, or insulting to women. Microaggressions necessitate a diverse strategy. Leaders may implement solutions by facilitating a vigorous interchange of ideas, which is the bedrock of creativity. They can offer opportunities for career development that concentrate on equality, diversity, and inclusivity.

Women are more likely than men to pursue higher education, and they are less likely to dropout before completing high school (Boatman et al. 3). On the other hand, men are more likely than women to seek a trades certificate (Frank and Frenette 14). In Canada, apprenticeship training is a standard route to being a skilled tradesperson. Women’s inclusion in male-dominated occupations has been recognized as increasing Canada’s supply of trained tradespeople (Frank and Frenette 21). In trades, women are underrepresented, accounting for about 14 percent of apprenticeship applications in 2019 (Frank and Frenette 17). They are also overrepresented in sales and service-related training. In 2019, nearly half of women applicants were enrolled in hairstylists, estheticians, and foodservice programs. The few women who enrolled in male-dominated trades programs were less likely to obtain a certificate than their male counterparts. From the above statistics, initiatives should be based on encouraging more women into the male-dominated fields, which pay higher than just ensuring they get an education.

Women are said to have nurturing personalities. Men are thought to be more suitable for jobs that need physical strength, like construction. Gender segregation is directly caused by these societal beliefs linked with different activities in the various industries. Even among college students, both men and women continue to seek gender-specific courses of study (Cohen). Ironically, they use their freedom to reinforce conventional gendered roles. As a result, gender segregation persists throughout professional disciplines. It is evident in the areas of study and professional specializations. Workshops such as by McKinsey & Company indicate that women are under-represented in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) fields (23 percent), entrepreneurship (29 percent), and politicians (29 percent). According to the Women Matter conference, women are 30% less likely than men to advance to management from entry-level roles and 60% less in senior executive roles (McKinsey & Company). Whereas outstanding women have ascended to the top positions, just a small number of women hold CEO roles.

Various issues lead to occupational gender segregation, mostly systematic behavior (Padavic et al. 100). Gender stereotyping is a significant driver of occupational segregation since it restricts younger people’s options and goals and groups them into disciplines commonly associated with their gender. Occupational gender segregation significantly lowers women’s wages, increasing the gender wage gap. Some forms of prejudice are overt and covert, while others result from unconscious biases and preconceptions. Prejudices can emerge as biased views on and behaviors toward an individual or group. The biases influence behavior. Conscious biases involve influencing others’ actions intentionally. Even though people might debate whether conscious or unconscious bias is worse, both types are responsible for biased actions and have negative consequences. According to research, unconscious gender prejudice pervades society and perpetuates gender inequity even when equality is legally advanced (Mascarenhas et al. 1). Even though conventional gender roles are not the norm in society, research has revealed that most individuals still retain unconscious biases arising from stereotypes.

It is important to note that although women face inequalities through occupational gender segregation in Canada, women from minority communities face more challenges. This further highlights the interplay of ethnicity, race, and immigration status in occupational gender segregation. From a personal perspective, living in a place where occupational gender segregation has a distinct impact on immigrants and women of color than on white women. Immigrant women in Canada, in my opinion, are more vulnerable to the adverse effects of occupational gender segregation because they are abused, alienated, and discriminated against by employers and coworkers based on their races and ethnicities. Immigrant women in Canada face workplace marginalization, overworking, and discrimination (Jagire 1). They also experience role reversals, as they are “breadwinners,” making their lives even more difficult. The structural and historical elements that have supported the oppression of immigrants, especially women, have been accepted as the norm. In some cases, these elements have been promoted by policies.

Recent studies, for example, one by Tettey and Puplampu, highlight the experiences of immigrant women in Canada (1). The study notes that Canada has implemented many policies to enhance the chances of persons afflicted by racial prejudice, including the Multiculturalism Act. The presence of psychological, institutional, and systemic difficulties is a huge concern, creating the illusion that there are still many people and organizations that would rather keep the status quo with its fundamentally unfair norms and procedures.

When businesses fail to achieve workplace gender equality and eliminate occupational gender segregation, there are negative consequences. The ILO highlights the increased economic advantage for businesses having at least 30% women representation at all levels and decision-making in their 2019 study on Women in Business and Management: The Business Case for Change (International Labour Organization). Gender equality in the workplace will help more than just the Canadian economy and individual enterprises. Although companies have put forth initiatives to boost women’s economic empowerment in professional life, new and revolutionary measures are required. Economic empowerment and gender equality for women would necessitate aggressive and transformational initiatives from different stakeholders. The government, businesses, employers’ and workers’ groups, and civil society should all be involved in a multi-stakeholder system. The private sector is also crucial in creating an environment where women may actively contribute and prosper in the economy. Companies should empower women in the workplace through intentional, transformational, and quantifiable workplace policies and programs. Workplace policies are essential in supplementing, reinforcing, and enhancing national legislation and rules and stimulating significant transformation throughout communities.

Research shows significant gender variations in acquiring career opportunities, education, and promotion are independent of one’s productivity qualities (O’Leary 5). For example, there is mounting evidence that evaluators’ biases in evaluating women decrease women’s chances of getting a job or promotion compared to similarly competent male applicants. It is essential to discover how evaluator bias impacts pay structure to benefit men at the expense of women. The “glass ceiling” bias, which prevents women from reaching the higher ranks of the professional hierarchy, has been identified as a predictor of the gender pay disparity. Glass ceiling bias is a perceived barrier to women, especially minorities, getting to the top management positions.Although Canada ranks above the OECCD average glass-ceiling index, efforts should be made to top the list. It may also be an indicator of the remaining gender pay gap.

The evolution of women’s labor-market outcomes during the twentieth century is a complex problem in Canada (Cortés and Pan 2). Gender equality is more important than ever in Canada as the nature of the Canadian economy and employment evolve. Despite the female labor force increase and the reduction in the wage gap, women remain concentrated in certain occupations and organizational levels (Cortés and Pan 13). The data from census records and the Labour Force Survey provide a suitable basic framework for changing the dynamics of occupational segregation.

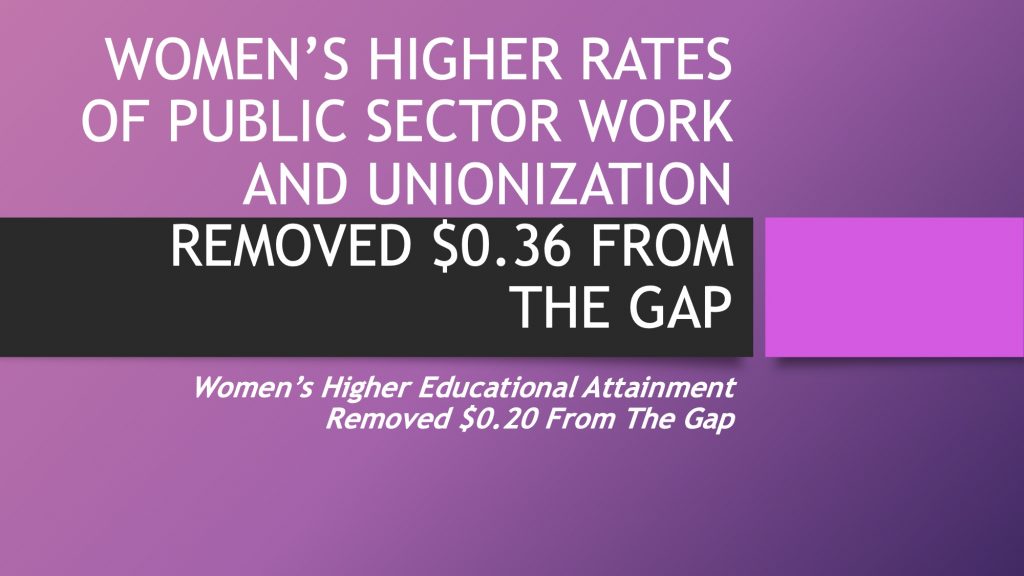

In theory, when women are crammed into a small number of female-dominated occupations, the oversupply in such professions should lower their wages. Economic and social historians have investigated these shifts. In Canada, women entered the education and health sectors (at the cost of clerical professions) as working conditions in these fields improved, mainly owing to union representation. By 1970, Canada’s health and education industries were heavily unionized, with extraordinarily high percentages of women (Pelletier and Patterson 8). Unions negotiated equal pay requirements into contracts. Collective bargaining was a potent tool available to unions for closing wage gaps. Unions utilized their advocacy influence to advocate legislation eliminating gender gaps in the workplace. Unions could directly oppose the wage gap by making such precise demands.

Notably, labor policies meant to mitigate the consequences of horizontal segregation have not produced the desired results since, over time, this segregation has resulted in the concretization of gender role stereotypes (Pelletier and Patterson 8). From the interview, the advocate for gender equality notes that the Canadian government has been inadequate in addressing occupational gender segregation. There is still more work to address the problems women face in the workplace linked to their gender. There should be a focus on the intersectionality of race, gender, and other identities from their experiences in the workplace. Individual identities should not be a barrier to policies that encourage equitable job opportunities.

The gender gap in Canadian institutions prevents the country from attracting knowledgeable and experienced individuals (Mascarenhas et al. 2). Workplace culture plays a vital role in advancing or discouraging occupational gender segregation. Male-dominated companies may foster a workplace culture that undervalues employees with family commitments, in this case, women. Respondents stated that this would make women’s work-life balance more complex and take the focus away from their projects (Mascarenhas et al. 4). Studies on the influence of occupational gender segregation on female workplace choices have shown that the perceived gender segregation may be deliberate (Padavic et al. 65). This issue is expected because women seek non-monetary rewards, including flexible schedules owing to childcare responsibilities.

An impediment to gender-diverse employment policies may be seen in male-dominated sectors, wherein stereotyping causes most women to avoid occupations conventionally associated with men. The women avoid studying and seeking male-dominated professions due to the stereotype. Women may be interested in these positions, but many are discouraged because they believe the workplace culture will dismiss them. Gender equality in higher education should aim in Canada to minimize occupational segregation. New policies and realistic and inventive solutions are required for women to achieve this in academic institutions. The workplace in Canada can achieve this equality by encouraging women to expand their higher education fields and provide such possibilities. It would eventually have a favorable impact on occupational gender segregation. Many students pick careers based on their high school experiences; thus, practical university projects should expand on their high school experiences.

Over the last several decades, women have made significant strides in education and schooling; in terms of education, women outperform males on average (Pelletier and Patterson 11). This gender disparity is visible even at an early age. Gender inequalities among young adults are considerably more evident, especially since more women than males are enrolled in university. However, judging by the impacts of educational achievement, culture, and institutional involvement, the chances of eliminating gender segregation are dismal in the short term. There are well-documented performance and opportunities gaps in schools based on poverty and ethnic background. These accountability requirements necessitate disclosing academic proficiency by gender, but there is no specific requirement. The majority of the challenges that women confront are sociological and cultural. They begin to discriminate against women as soon as they start kindergarten.

Gender stereotyping is prevalent in the workplace and organizations, resulting in disparities at all stages of the recruitment and selection process (McKinsey & Company). Recruitment is an initial step in achieving gender equality in the workplace. However, hiring and retaining female employees remains a difficulty. They are devalued, underpaid, and unable to establish a work-life balance. All stakeholders in the professional sector should raise awareness of gender equality and dispel common stereotypes. They should address systematic inequality caused by undervaluing conventional “women’s jobs” by implementing pay systems that assure equal compensation for equal effort. Manufacturing may be thought of as a man’s domain. This is reflected in the gender representation in this industry. Manufacturing is a rapidly developing industry in Canada, but women are less well-positioned to benefit from job growth in this sector, where they account for only 28 percent of employment (McKinsey & Company). This number has been constant throughout the last ten years.

A study found that women were underrepresented in academia in Canada (Mascarenhas et al.). This study pointed to discrimination in gender practices as a significant contributing factor. Researchers discovered a considerable gender gap at a research center that had been there for almost fifteen years. The study calls for active initiatives to close the gap and guarantee that

A study found that women were underrepresented in academia in Canada (Mascarenhas et al.). This study pointed to discrimination in gender practices as a significant contributing factor. Researchers discovered a considerable gender gap at a research center that had been there for almost fifteen years. The study calls for active initiatives to close the gap and guarantee that stakeholders in various professions appreciate the diversity among individuals. Socializing and preconceptions that determine roles and functions before education in a higher education institution also impact the road to professional life. Even though gender stereotypes emerge early in life, academic achievement is possible, provided opportunities are accessible. Several issues have been proposed as contributing causes, including the possibility of implicit bias in hiring. For instance, participants in the study by Mascarenhas et al. did not express a belief that there is a deliberate prejudice towards women inside the organization.

Some studies have revealed that societal progress in terms of gender segregation is primarily one-sided, with women preferring entry into male-dominated occupations over the opposite because female-dominated occupations pay less (Yavorsky 4). If women earn less than males on average, it logically follows that female-dominated occupations pay less. Women may be assigned to positions with lower predicted pay. This might be due to organizations’ recruitment procedures, women’s decreased levels of skills and knowledge, or women acting on their own professional “interests,” such as the desire to work flexible schedules to care for family members. Cultural views of the jobs that men and women should and wish to undertake are critical drivers of change. Preconceptions make it more difficult to achieve economic equality between men and women, but they also significantly impact young people’s educational achievement and career opportunities. Stereotypes play a role in both the academic and household environments. They emphasize, in particular, how parents and teachers adopt, sometimes unintentionally, gender socialization processes, which push young individuals toward careers that are regarded as acceptable for their gender.

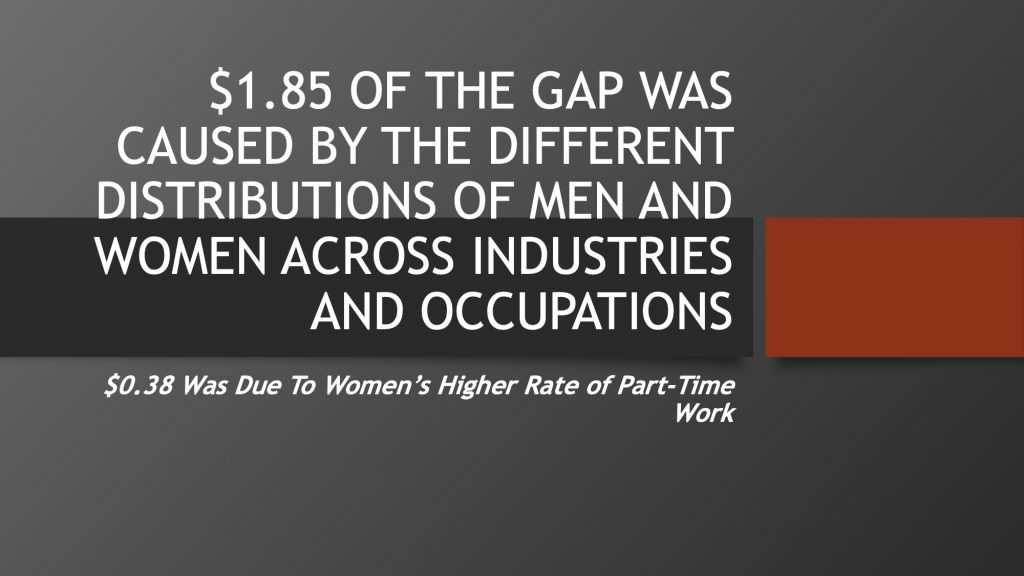

From 1998 to 2018, the gender pay gap in Canada has reduced. In 1998, it was $5.17 and had shrunk by $1.04 in 2018 (Pelletier and Patterson 5). This narrowing of the gender wage gap was mainly attributed to differences in the balance of men and women across different professions. Women had improved education, and there was a drop in the unionization of men. The distribution of men and women in various sectors and women’s overrepresentation in part-time employment were the most critical causes driving the wage gap in 2018 (Pelletier and Patterson 4). Even though women earned a lower wage for working part-time than men, women’s increased probability of working part-time led to the gender wage gap growth. These were also the most significant causative factors for the difference in 1998.Although women are more represented in the workplace, they are overrepresented in particular professions deemed normal for women to pursue. This phenomenon further underlines the prevalence of occupational gender segregation.

Most women shifting between jobs and industries may have to obtain more training to satisfy the demand for new skills (Devillard et al. 33). Employees may need to crossover into work opportunities and gain skills that future employers will require to stay in the workforce. These job prospects will almost certainly need advanced education and can be well-paying (Devillard etal. 33). Men and women in the labor sector will almost certainly need to retrain or reskill to gain the necessary abilities and expertise for future occupations. Based on existing gender inequalities, such as unequal allocation of unpaid care duties, women may encounter additional hurdles in professional growth. Furthermore, there are additional gender pay gaps and intersectionality aspects to consider. These barriers will mean more occupational gender segregation in the future workspace.

Various stakeholders have suggested interventions to reduce gender inequality and occupational gender segregation. Various policy options are necessary to minimize occupational gender segregation and the pay gap. When it comes to launching a professional path, girls and women need more assistance to make educated decisions. This endeavor will guarantee that students do not base their job choices on the relative earning prospects of other professions. More focused development and apprenticeship initiatives are needed to lower the obstacles for women interested in trades. Women’s recruitment and retention operations must be audited by both training institutions and employers, especially when receiving government funding.

The factors affecting the net segregation wage gap may differ according to the sector. They necessitate more significant in-depth research within smaller regions and industrial groups. Job qualities and compensation structures in specific gender-dominated professions might be compared at the industry level. The strategy should be comparable to current large corporations’ wage equality policies. Organizations should strive to do more to narrow the gap and transform purpose into actions. Some Canadian organizations have made strides toward gender equality. In addition to encountering difficulties in advancing in their careers, women feel excluded in the workplace and suffer prejudice daily. The gender equality roadmap consists of an environment that fosters gender diversity and inclusion within a company.

In conclusion, race, gender, immigration status, nationality, and ethnic background expose minority women to various forms of systemic discrimination and underlying workplace barriers. This gender discrimination affects how women get hired and promoted and what careers they pursue. As compared to white women, the experiences of women from minority communities with occupational gender segregation; race, ethnicity, immigration, and nationality further aggravate occupational gender segregation. Given the significant impact that variations in occupational and industry distribution play and keep playing in understanding the history of the wage gap, this is an essential subject for future research. Understanding the cause and prevalence of gender segregation and why representation in specific occupations and sectors differ by gender might be beneficial in policymaking. It can also aid those attempting to eliminate gender inequalities in different fields.

Works Cited

Boatman, Angela, et al. ‘Understanding Loan Aversion inEducation: Evidence from High School Seniors, Community College Students, and Adults’. Aera Open, vol. 3, no. 1, 2017, p. 2332858416683649.

Cohen, Philip N. ‘The Persistence of Workplace Gender Segregation in the US’. Sociology Compass, vol. 7, no. 11, 2013, pp. 889–99.

Cortés, Patricia, and Jessica Pan. Children and the Remaining Gender Gaps in the Labor Market. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020.

Devillard, Sandrine, et al. The Present and Future of Women at Work in Canada. p. 92.

Fortin, Nicole M. ‘Increasing Earnings Inequality and the Gender Pay Gap in Canada: Prospects for Convergence’. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue Canadienne d’économique, vol. 52, no. 2, 2019, pp. 407–40.

Frank, Kristyn, and Marc Frenette. How Do Women in Male-Dominated Apprenticeships Fare in the Labour Market?2019, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2019008-eng.htm.

International Labour Organization, Bureau for Employers’. Women in Business and Management: The Business Case for Change. Report, 22 May 2019. www.ilo.org,http://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_700953/lang–en/index.htm.

Jagire, Jennifer. ‘Immigrant Women and Workplace in Canada: Organizing Agents for Social Change’. SAGE Open, vol. 9, no. 2, Apr. 2019, p. 2158244019853909. SAGE Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019853909.

Mascarenhas, Alekhya, et al. ‘Perceptions and Experiences of a Gender Gap at a Canadian Research Institute and Potential Strategies to Mitigate This Gap: A Sequential Mixed-Methods Study’. Canadian Medical Association Open Access Journal, vol. 5, no. 1, Feb. 2017, pp. E144–51. www.cmajopen.ca,https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20160114.

McKinsey & Company. Gender Equality | McKinsey & Company. 2021,https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/gender-equality.

O’Leary, Simon. ‘Graduates’ Experiences of, and Attitudes towards, the Inclusion of Employability-Related Support in Undergraduate Degree Programmes; Trends and Variations by Subject Discipline and Gender’. Journal of Education and Work, vol. 30, no. 1, 2017, pp. 84–105.

Padavic, Irene, et al. ‘Explaining the Persistence of Gender Inequality: The Work–Family Narrative as a Social Defense against the 24/7 Work Culture’. Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 65, no. 1, 2020, pp. 61–111.

Pelletier, Rachelle, and Martha Patterson. The Gender Wage Gap in Canada: 1998 to 2018. 7 Oct. 2019,https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-004-m/75-004-m2019004-eng.htm.

Tettey, Wisdom J., and Korbla P. Puplampu, editors. The African Diaspora in Canada: Negotiating Identity and Belonging. University of Calgary Press, 2006. DOI.org (Crossref),https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv6gqw99.

Yavorsky, Jill Evelyn. Inequality in Hiring: Gendered and Classed Discrimination in the Labor Market. The Ohio State University, 2017.