Angelo Tarica

Angelo Tarica is a student who is graduating from Capilano University this year with a bachelor’s degree in psychology. After graduation, Angelo plans to apply to graduate schools to obtain his masters degree in a counselling related discipline. Angelo’s goal in the future is to become a therapist and help individuals with their psychological health.

Image created by Angelo Tarica.

At 26 years of age, I never thought I would find myself graduating from a university with a bachelor’s degree. For a large portion of my life (especially high school), I was the epitome of a terrible student. School never really grabbed my attention. It was tedious, boring, and something that I dreaded going to.

My upbringing was nothing special, I was born into a middle-class family who attended to my every need. I had a roof over my head, lived in a safe neighbourhood, went to multiple private schools, and was involved in a plethora of extracurricular activities. I had a strong emphasis on Italian culture growing up which definitely instilled a value system based on community rather than the traditional western view of individualism. Given these circumstances, you would think my life couldn’t possibly have the potential to go down hill, but it did.

My perspective on life would drastically change after leaving high school. After turning 19 and experiencing a brief stint in university, I found the career of firefighting to be something worth pursuing. For a year and a half,I dedicated my life to trying to achieve all the prerequisites to get into the program. After a long grueling period of discipline and sacrifice, I finally got accepted into the program.

The first few weeks of the firefighting program was the epitome of hell on earth. Waking up at four in the morning to train for eight hours a day doesn’t sound too appealing to the average person, but to me, it was a temporary sacrifice in exchange for a future meaningful career. Unfortunately, three weeks before graduation, something would happen that would change the direction of my life. While doing a routine fire drill, I ended up injuring my back due to an awkward range of motion. A couple days after the incident, a meeting with my physician would solidify a one-way ticket to the deterioration of my mental health. After being told by my doctor that it would not be recommended to go back into the program with a back injury, my life turned upside-down.

For the next year, I ruminated extensively in my bedroom asking myself what was the point of life? I spent two years of my life trying to achieve a dream all for it to be ripped away by a routine fire drill that I’ve done several times? I never would have thought that such a state of mind could have ever existed. I became a recluse, completely isolating myself from the outside world, trying to cope with my feelings of depression through copious amounts of food and excessive video game usage. Life to me felt like a huge waste of time, I was stuck in a cycle of hopelessness and meaninglessness.

After one and a half years of misery, a YouTube video of all things convinced me to try going back to the gym and doing something productive with my life. At first, I was super reluctant to go because while I was depressed, I avoided doing anything because in my mind, everything would fall apart as soon as I did. My mind was full of cognitive distortions that tried to convince me that going anywhere was a waste of time and would just result in failure. It was a battle between my current state of mind and my motivation to do something. After mustering up the energy to go to the gym and noticing I lost 3 pounds after just one week of training, this simple trivial task sparked a massive domino effect in my life.

Overtime, my negative thoughts started to dissipate and I went from a perspective of nihilism to a sense of optimism about the world. It was at this time of emotional bliss that I realized that maybe helping someone who was in my position could be my new calling. After months of researching extensively about mental health and being fascinated by it all, I decided that I wanted to become some sort of therapist and that psychology would get me there. This hardship single handily reconstructed my whole belief system in regards to how I see the world. At the age of 22, the kid who never liked school found himself back in education.

It was through my own personal experiences with mental health that I started developing an interest in psychopathology. I started to become fascinated by how our environment impacted our thoughts, behaviours, emotions, and mood. How our childhood played such an important role in how we develop biologically, psychologically, and socially. Through the study of psychology, I learned a variety of new skills that expanded not only my intellectual framework regarding mental health, but also the development of important life skills. These skills included becoming more critical of information I was viewing, utilizing logic and reason to construct sound arguments, and improving interpersonal communication through the lens of empathy and understanding. From the academic perspective, all my psychology courses have taught me so much about human behaviour. I’ve learned extensively about the different types of mental illness’s (abnormal psychology), how other people effect our own thoughts and behaviours (social psychology), which parts of the brain are responsible for specific functions (neuropsychology), the different methods of counselling individuals with mental distress (clinical psychology), and so much more.

After a long journey through academia, my future plans heavily rely on going back to university to further expand my knowledge about mental health and human behaviour. I plan on applying to graduate school in order to achieve a masters degree in a counselling related discipline to become a mental health clinician(therapist). My end goal is to be able to give back to my community and be a positive influence for the next generation of people who are struggling with life.

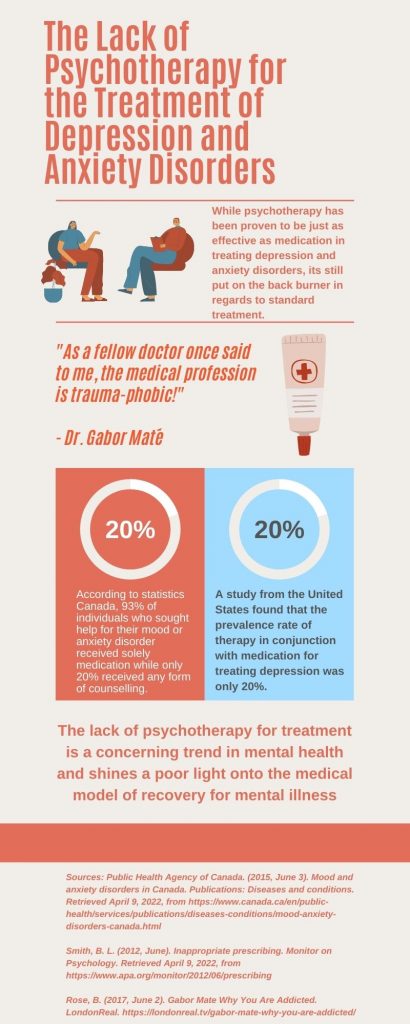

After four years of accumulating a deeper understanding of the human condition, I noticed a weird pattern that was going on within the system of mental health through my course material. I started stumbling over concerning statistics regarding the administration of psychiatric medication for depression and anxiety. The more that I looked into it, the more I felt that I needed to address this concerning trend in mental health treatment. Synthesizing all the material I’ve learned over the years, I wanted to apply a level of analysis towards the current mental health paradigm. With one in two Canadians having or will have some form of mental illness by the age of 40(CAMH, n.d.), It is important that the general public have some level of mental health education that makes them more aware of various treatments. This article seeks to address the excessive use of psychological medication for individuals suffering from depression and anxiety disorders within the current mental health system.

The narrow focus on depression and anxiety disorders within this article is not an attempt to reduce the significance of other mental health disorders, but to address the most common psychopathologies that are manifesting within the general population. Within the Canadian population, the most common mental illnesses are mood and anxiety disorders, effecting an estimated 11.6% of Canadians aged 18 years and older (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2015). These rates have increased drastically since the presence of the COVID-19 pandemic with 25% of Canadians screening positive for mental health symptoms associated with depression, anxiety, or PTSD (Statistics Canada, 2021). With more people passing through the mental health system, it’s important that individuals have a comprehensive understanding of all the treatment options available to them. But, within the current mental health system it seems that certain treatments, particularly medication, are being favoured a lot more than other effective treatments.

My position regarding this topic is that within the current mental health paradigm, there is an overemphasis on psychiatric medication. With the vast amounts of research indicating that these particular disorders could be treated just as effectively through means of psychotherapy, the question becomes why is there an excessive use of these kinds of medications? This article isn’t an attempt to undermine the efficacy of medication for mental illness, rather it’s a critique of the frivolous nature of drug administration within the medical industry when other forms of treatment are just as effective.

Image created by Angelo Tarica.

The overreliance on psychotropic drugs within the medical industry is becoming more apparent as decades of drug administration statistics become available. The American Psychological Association (APA) published an article titled “Inappropriate prescribing” that attempted to shine a light on the excessive use of psychological medication for mental illness (Smith, 2012). Statistics coming from the United States indicate a concerning trend in regards to the administration of psychological medication. Early preliminary research starting all the way back from 1996 indicated that only 33.3% of individuals who sought out treatment for depression also received therapy in conjunction with their medication (Smith, 2012). A follow up survey in 2005 of 50,000 medical surveys indicated that rates of psychotherapy in conjunction with drug treatment actually decreased from 33.3%to only 20% of individuals (Smith, 2012). However, the evidence for excessive use of medication doesn’t stop there.

One research study distributed a survey to 700 individuals who were prescribed antidepressant medication in an attempt to see if the medication they were prescribed was warranted (Lane, 2009). The study concluded that only 20% of the 700 participants were actually screened for a depressive disorder (meaning that 80% were not even screened for a diagnosis) (Lane, 2009). The study also illuminated that 70% of the individuals that participated in the survey did not have sufficient symptomology to be diagnosed with a depressive disorder (Lane, 2009).

In regards to anxiety disorders, unfortunately, its the same thing. Statistics coming from the Canadian government regarding mood and anxiety disorders found that 93% of individuals who sought help for their disorders received medication, but only 20% received psychotherapy (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2015).

For many individuals suffering from an anxiety disorder, they to will often be prescribed antidepressant medication to combat their anxiety. Why is this? Well, let’s just say that antianxiety medications such as the class of benzodiazepines are incredibly powerful drugs that are known to have many significant health risks that include chemical dependency (addiction), increase in reckless behaviour, and risk for overdose (Hairston, 2020). Since antianxiety medications have harsher side effect profiles in comparison to the antidepressant class, many clinicians prefer to use SSRIs as first-line treatment for anxiety (Hairston, 2022).

One of the reasons for my emphasis on psychotherapy (talk therapy) over medication involves some of the pitfall’s current psychological literature exposes with antianxiety and antidepressant medication. Starting with antidepressant medication, anew study that focused on the discontinuation of antidepressant medication found that approximately 56% of people who ceased using their medication experienced a relapse of their depressive symptoms after 1 year (Lewis et al., 2021). Another study that looked at the rate of relapse amongst patients who experienced remission from SSRI’s found that 42-55.6% of participants who stopped using SSRIs ended up experiencing depressive symptoms again (Henssler et al., 2019).

In regards to anxiety disorders, one study found that out of the 5233 patients that discontinued their antidepressant treatment for anxiety related symptoms, 36.4%(over one-third) ended up relapsing after a 52-week period (Batelaan et al., 2017). Another study that looked at five anxiety disorders (panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder,PTSD, and OCD) concluded that after the discontinuation of antidepressant medication, rate of relapse hovered between 26-45% (Donovan et al., 2010). As you can see, medication for the treatment of depression and anxiety definitely has considerable room for improvement, considering many individuals relapse.

Image created by Angelo Tarica.

When analyzing these studies, its clear that the underlying mechanisms of antidepressant and antianxiety medication is to act as a mental painkiller that seeks to reduce the psychological distress associated with depression and anxiety rather than being a medication that has active properties in curing the individual of these symptoms. The process of symptomatic management for individuals suffering from depression and anxiety could be a concern if one wants to address the root cause of their psychological pain rather than just masking it through pharmacology. This is where other forms of treatments such as psychotherapy provide tremendous benefit.

Depression can manifest itself in a number of ways. There are many sophisticated models proposed by scientists that could explain how someone may develop depression over the course of their lifetime. However, one important variable that impacts how one may develop depression over the course of their lifetime stems from childhood. According to a self-report questionnaire that interviewed 349 patients that struggled with chronic depression found that 75.6% of these individuals reporting having a history of childhood trauma (experiencing a traumatic event in early development) (Negele et al., 2015). The study also concluded that individuals who experienced multiple traumatic experiences or experienced sexual/emotional abuse in childhood ended up having more severe forms of depression (Negele et al., 2015). Given the high incidence of trauma amongst depressed patients, therapy seeks to address this trauma directly instead of masking the symptoms.

The current consensus within mental health research is that certain therapies such as cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) and antidepressant medication are equally beneficial in treating depression, with some evidence indicating that these two treatments combined can provide maximum effects (Gavin, 2019). In a large-meta-analysis consisting of 1,511 patients that were treated with either medication or psychotherapy for their depression found that after a 16-week period, those who received cognitive-behavioural therapy achieved slightly higher remission than those on medication (47.9% vs 40.7%) (Amick et al., 2015). Even though the rate of remission was higher for CBT, the difference between the two was not statistically significant (Amick et al., 2015). The researchers concluded that both treatments for depression did not differ greatly in there potential to treat depression (Amick et al., 2015). So, while it seems that therapy such as CBT is empirically just as effective as medication, the statistics regarding the administration of it compared to medication is woefully mismatched.

The research for anxiety disorders is also in favour for therapy. A large-scale study that consisted of over 13,000 participants from 101 trials found that the most effective treatment that best increased the rate of remission for individuals who suffered from social anxiety disorder (SAD) was through cognitive-behavioural therapy(Mayo-Wilson et al., 2014). CB Thas also been found to greatly reduce the anxiety of other anxiety related disorders as well. Studies have shown that a modified version of CBT with medication was the best option for sufferers of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and CBT was shown to drastically decrease the main symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (Hairston, 2020).

So, given all the empirical evidence surrounding the efficacy of treating depression and anxiety disorders through means of psychotherapy, why is there still an overemphasis on medication for treating these mental illnesses? The first explanation comes from Dr. Gordon, psychology professor at the University of Victoria and Capilano University. Dr. Gordon has an abundance of knowledge regarding neuropsychological processes and drug science that I felt she would be the perfect person to interview regarding the topic of excessive psychological medication. In response to my question about overreliance on medication in regards to treating these disorders in the current mental health paradigm, Dr. Gordon had this to say:

“Yes, and it happens at several levels. First, well, you have to understand how the system works, where psychological health care is not covered by MSP, right? Only physiological. So, it always begins with a general practitioner or somebody comes in and says, you know, I’m not feeling okay. I’m feeling really down and we’ve now already had a problem in the system where GPs are acting as if they’re psychologists, which they shouldn’t be” (I. Gordon, personal communication, February 25th, 2022).

Image created by Angelo Tarica.

Dr. Gordon highlights one important problem within the current mental health system, which is the use of general practitioners for the distribution of psychological medication. Dr. Gordon’s observations are also supported by the APA, which points out that within the United States, close to 4 out of 5 prescriptions for mental health drugs were filled out by physicians, not a mental health professional (such as a psychiatrist)(Smith, 2012). This raises a broader question about why aren’t we letting mental health professionals such as psychiatrists and psychologists make these informed judgments on whether someone would benefit from a psychotropic medication? The current system allows physicians that are not as informed about mental illness as mental health professionals to provide medication, which definitely is one factor that is contributing to the overemphasis on medication for treatment.

Dr. Gordon points out another problem with the current system, which is the inaccessibility of psychotherapy compared to the accessibility of medication. When I questioned Dr. Gordon about why aren’t we treating depression and anxiety with therapy given its effectiveness is just as high as medication, she responded with:

“We know that the combination of both CBT and medication is synergistic, compared to each one alone, and they are comparable. So, if you start someone off on a pill, or you start someone off on just CBT, you will get to the same outcome. Absolutely. It’s when you combine them that you just see some amazing outcomes. The question is, why not? Why aren’t we already there? Why aren’t we offering, because psychotherapy is a psychologist who cost $230 an hour, but your general practitioner, he runs your card, he gets his $15, you get your 15 minutes, you can write the prescription and off you go. So, we just have access to medication through a system that’s not ideal and there’s very little access to CBT from a fiscal perspective, so who gets involved with that?And when pills are easier, we tend to see that even the clientele gravitate toward the pill, because they don’t need that, like I’m busy throughout the day” (I. Gordon, personal communication, February 25th, 2022).

Dr. Gordon reveals a dark truth about the current system, which is that therapy is a lot more inaccessible to the general public than medication. Not only does therapy tend to be a lot more expensive than medication, but therapy is also an intense process that takes weeks or months to see results from. When comparing therapy versus medication, its clear that medication has an advantage of being extremely easy to administer (1 pill a day), being less expensive than therapy, and gives people psychological relief almost instantly (if they respond to the medication of course). Even though therapy through the literature seems to be as effective as medication (and both medication and therapy together seem to have the best results), the general population still goes down the pharmacological root because of convenience. No one wants to spend long hours in a therapist’s office talking about things that could make them extremely uncomfortable when one pill can relieve them of their psychological misery.

That’s how the current mental health system operates though, the system has been engulfed by the medical model that attempts to reduce people’s problems strictly from a biological perspective. Dr. Gabor Mate, a best-selling author and physician that has worked with individuals with addiction and mental illness in Vancouver’s downtown east side has fought back against the overmedicalization of mental health. Dr. Mate often criticizes the medical model of recovery for mental illness for being incredibly ineffective in actually treating an individual’s psychological pain. In an interview with the London Real, Dr. Gabor criticizes the medical industry by claiming that:

“The average medical student until very recently has never even heard of the word trauma in their education, it doesn’t show up. We don’t talk about it.We don’t talk about its impact on the brain, on the personality, on the emotional life of people and its impact on people’s physical health. Its not a word that we mention, were trauma-phobic.As a fellow doctor once said to me, the medical profession is trauma-phobic! Psychiatrists these days are trained mostly in this biological model of psychiatry where everything comes down to a biological brain disease, here let’s give you a pill” (Rose, 2017).

Dr. Mate emphasizes that people with mental illness are not just individuals who suffer from a biological brain disease, but instead are individuals who carry a lot of emotional pain from their childhood. Dr. Mate’s assessment on mental illness is completely valid as there are 13 countless of peer reviewed studies that show a significant correlation between childhood trauma and future psychological development. The truth of the matter is that the medical model of recovery simply boils down mental health to a chemical imbalance of neural activity as the source of mental illness. However, this narrow focus on strictly biological causes of psychopathology misses an abundance of variables that contribute to how someone forms a mental illness.

Image created by Angelo Tarica

So, given all the information presented so far, what would be some solutions that would make the mental health system more effective in treating psychological pain? Through an analysis of the literature, I have developed some ideas that could change how the mental health system operates.

Firstly, I would like to see more mental health professionals in charge of administering psychological medication than family doctors. Statistically, it seems that general practitioners prescribe the majority of the psychiatric drugs, which is a huge problem. If a patient is going to receive psychotropic medication for their symptoms, they should at least be assessed by a mental health professional that has more knowledge about mental health symptoms than a general practitioner. These mental health professionals could include a psychiatrist, psychologist, counsellor, or social worker.

Secondly, therapy needs to be more accessible to the general public. Currently, under the British Columbia medical services plan (MSP), therapy through counsellors and psychologists are not covered. Given how expensive therapy could be, its not a surprise that many individuals suffer in silence because of the inability to be able to afford treatment. Given all the evidence of how good therapy is for the recovery of mental illness, especially in comparison to medication, its unacceptable at this point that psychotherapy isn’t covered. There needs to be a large-scale reform of health coverage (MSP)that extends to psychotherapy. This policy reform isa mandatory requirement that will allow the working-class people who are suffering from psychological distress to actually access mental health treatments they truly need.

Lastly, there needs to be a wider spread of education to the general public regarding therapy. Many people in the western world, including patients, have succumb to the medical model of mental illness. While therapy is generally widely accepted by society, there are still individuals who are stuck in the mindset that if one is not being treated with a pill, how can other treatments such as talk therapy even be useful? I have had many conversations with people who were hesitant with therapy, but were completely shocked when I told them that the psychological literature indicates that psychotherapy for depression and anxiety is just as effective, if not sometimes more effective, than medication. It seems that a lot of people are still under the impression that if something isn’t a drug, it wont help you. More knowledge about the efficacy of psychotherapy should be presented towards the general population through informative and accurate ad campaigns spread across social media platforms.

In conclusion, the point I want to drag home is that there is an overreliance on medication for treating individuals with anxiety and depression within the current mental health paradigm. There are many people out there who are suffering from trauma and sometimes medication is not going to help them get through their complicated problems. I’m not anti-medication (as there are many circumstances where medication is needed), but all I’m advocating for is a higher prevalence of psychotherapy in conjunction with pharmacological treatment. Therapy is such an important tool in addressing people’s emotional pain, but as it stands, its currently being put on the back burner because of the overmedicalization of mental health. Why deprive the general population of an empirically valid treatment that has the potential to cure them of their ailment? Let’s make therapy accessible to the population and get people the proper help they need!

References

Amick, H. R., Gartlehner, G., Gaynes, B. N., Forneris, C., Asher, G. N., Morgan, L. C., Coker-Schwimmer, E., Boland, E., Lux, L. J., Gaylord, S., Bann, C., Pierl, C. B., & Lohr, K. N. (2015). Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants and cognitive behavioral therapies in initial treatment of major depressive disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 351. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6019

Batelaan, N. M., Bosman, R. C., Muntingh, A., Scholten, W. D., Huijbregts, K. M., & van Balkom, A. J. (2017). Risk of relapse after antidepressant discontinuation in anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis of Relapse Prevention Trials. BMJ, 358.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j3927

CAMH. (n.d.). The crisis is real. Driving Change. Retrieved April 9, 2022, from https://www.camh.ca/en/driving-change/the-crisis-is-real

Donovan, M. R., Glue, P., Kolluri, S., & Emir, B. (2010). Comparative efficacy of antidepressants in preventing relapse in anxiety disorders —a meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 123(1-3), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.021

Gavin, K. (2019, October 29). In the Long Run, Drugs & Talk therapy hold same value for depression patients. University of Michigan. Retrieved April 10, 2022, from https://labblog.uofmhealth.org/rounds/long-run-drugs-talk-therapy-hold-same-value-for-depression-patients

Hairston, S. (2020, February 23). Therapy vs medication: Everything you need to know to make the right decision. Open Counseling. Retrieved April 9, 2022, from https://www.opencounseling.com/blog/therapy-vs-medication-your-decision-making-guide#one

Henssler, J., Heinz, A., Brandt, L., & Bschor, T. (2019). Antidepressant withdrawal and rebound phenomena. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 116(20), 355–361. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2019.0355

Lane, C. (2009, May 11). Overprescribing antidepressants. Psychology Today. Retrieved April 9, 2022, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/side-effects/200905/overprescribing-antidepressants

Lewis, G., Marston, L., Duffy, L., Freemantle, N., Gilbody, S., Hunter, R., Kendrick, T., Kessler, D., Mangin, D., King, M., Lanham, P., Moore, M., Nazareth, I., Wiles, N., Bacon, F., Bird, M., Brabyn, S., Burns, A., Clarke, C. S., … Lewis, G. (2021). Maintenance or discontinuation of antidepressants in primary care. New England Journal of Medicine, 385(14), 1257–1267. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2106356

Mayo-Wilson, E., Dias, S., Mavranezouli, I., Kew, K., Clark, D. M., Ades, A. E., & Pilling, S. (2014). Psychological and pharmacological interventions for social anxiety disorder in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(5), 368–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(14)70329-3

Negele, A., Kaufhold, J., Kallenbach, L., & Leuzinger-Bohleber, M. (2015). Childhood trauma and its relation to chronic depression in adulthood. Depression Research and Treatment, 2015, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/650804

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2015, June 3). Mood and anxiety disorders in Canada. Publications: Diseases and conditions. Retrieved April 9, 2022, from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/mood-anxiety-disorders-canada.html

Rose, B. (2017, June 2). Gabor Mate Why You Are Addicted. LondonReal. https://londonreal.tv/gabor-mate-why-you-are-addicted/

Smith, B. L. (2012, June). Inappropriate prescribing. Monitor on Psychology. Retrieved April 9, 2022, from https://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/06/prescribing

Statistics Canada. (2021, October 4). Survey on covid-19 and mental health, February to May 2021. The Daily.Retrieved April 9, 2022, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210927/dq210927a-eng.htm